Photo provided by Marion Selfridge and Michaela Roos

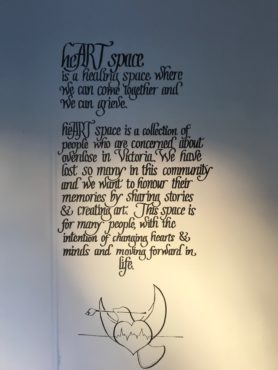

An awning covered with images of camas, lavender, and Garry oak still hangs over the front door of 821 Fort St., remembering the heARTspace pop-up gallery that lived there from Oct. 10–31. The awning was painted specifically for the gallery, which was designed as a grieving space for those who have lost a loved one to the opioid crisis.

heARTspace, which aimed to include members of Indigenous and street communities, was co-founded by Naomi Kennedy and Marion Selfridge. Art submissions were mostly memorial pieces created by friends and family members, though some pieces were created by those who had passed away and were submitted by their loved ones.

Artwork of all styles covered the space. Paintings, sketches, photographs, and poems hung on the walls. Sculptures and puppets sat on chairs and shelves around the room. Many of the pieces were portraits of the individuals being remembered. Underneath each piece of art was a bio. More often than not, the bio was not about the artist but the subject.

In the centre of the room was a large tree made of soft blankets and pillows. Paper birds hung from the branches, and each carried a handwritten message from a gallery visitor to a loved one. Treats and hot drinks covered a table at the back of the gallery, where volunteers stood watch over the space. A tissue box was tucked into each corner of the room.

By the end of its three-week run, the gallery had about 40 pieces on display.

According to Selfridge, who works for the Victoria Cool Aid Society, providing a physical space for people to grieve those who have died in the opioid crisis is important because the stigma attached to drug-related deaths makes it hard for loved ones to reach out for support.

The heARTspace gallery. Photo provided by Trudi Smith

“It gives it the importance that it deserves in the world, especially for grief that might be viewed as stigmatized,” says Selfridge. “For example, a number of the parents who came forward have been really struggling to find places where they can get support around the fact that their children have died, because people are like, ‘Well, they were a drug addict.’ Sometimes it’s hard that there’s all this other stuff going on. Just to say, ‘This is a space. This is somewhere we can come together,’ was a really big deal.”

Selfridge says that stigma has also contributed to the rising number of opioid-related deaths. Fear of the law and of ostracization leads people to use opioids alone. Many are not accessing resources like mental health support and safe injection sites, which are supervised by trained individuals armed with naloxone kits. In the midst of the fentanyl crisis, using alone is especially dangerous.

“As a result of this . . . notion of stigma, many people are dying,” says Selfridge. “People are dying of opioid overdose or poisoning when they are using a substance that they are afraid to tell people about or don’t want to tell people about, and so are using alone. That’s the issue. People are using by themselves. And they’re using substances that are unknown.”

According to the B.C. Coroners Service, there were 1 208 deaths due to illicit drug overdose between January and October 2017. 57.9 per cent of these deaths happened in private residences. None happened at supervised consumption or overdose prevention sites (safe injection sites).

Jennifer Howard lost her son to an accidental drug overdose containing fentanyl. She is a member of Moms Stop the Harm (MSTH), a network of families across Canada that have all lost a loved one to an overdose. A portrait of her son, Robby, was on display at heARTspace.

“I think art really is an expression, often for people, of feelings and emotions that they can’t put into words,” says Howard of heARTspace. “But it’s a tangible way of communicating. To me, as a viewer looking at the artwork, it really hits home. It’s very emotional to see, and it’s a tangible expression of such loss.”

For Howard, conversations like the ones facilitated at heARTspace play an important role in harm reduction.

One of the shrines in the heARTspace gallery. Photo provided by Marion Selfridge and Michaela Roos

“Robby was in that group of individuals that we’re having trouble reaching, in terms of the overdose, who use privately in their homes, with no one there,” said Howard. “We haven’t been able to reach out to them to prevent their deaths in an adequate way. For me, I believe that a lot of it has to do with stigma. I would say that was part of what Marion [Selfridge] brought to our community as well . . . we had a conversation about substance use disorder, and a part of that conversation in that space was talking about stigma.”

Through MSTH, Howard is working to prevent drug related deaths by advocating for improvements in healthcare and drug policy changes such as decriminalizing and legalizing certain drugs, advocating for more funding for treatment supports, and promoting measures to de-stigmatize substance use disorder.

“If I can find anything good that comes out of all of this loss, it’s that it is forcing us to have the conversation about substance use disorder,” says Howard. “My hope is through all this heartache and loss, through advocacy, like what Marion did, that we will hopefully change this for the better for people.”