My whole life has been plagued by racism, and it should not take a pandemic to reveal its ugly head

Imagine being put on the spotlight in a humiliating way, and then getting blamed for other people’s problems just because of assumptions made about your race. Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, reports about police brutality and its victims surfaced. All victims were people of colour, which provoked strong protests among racialized communities. In response to concern over racist attacks, universities and corporations have released statements supporting anti-racism. Protests in support of Black Lives Matter have received widespread support.

However, this is not enough. We need to begin to answer the questions raised by recent events, many of which address issues that have persisted throughout our history. And out of all of the questions, one stands out the most: why do racialized communities still need to fight for respect and value in Canada?

As a history major, I have read sources about racism in Canada. And yet I still do not have a definitive answer to that question.

What I do know is that history does not repeat itself, but the characteristics of past events can remind us of what is at stake in the present. Characteristics can be shown through ideologies or movements. This is why people compare current events to the past, so they can understand what is on the line. Currently, that is equality.

The mission for equality always seems to be out of reach. It’s like swatting a fly — you think you got it, but it flies away before you can catch it. All my life, I have been asking for equality as an Asian-Canadian. As the first Canadian-born generation in my family, I believed that I could express my culture to everyone. Sadly, people made presumptions about me because of my race. Presumptions are based on myths and stories, but some people take them as facts.

The only hope that I carried is my mother’s story. Her story was part of my backbone in the fight against racism. Her experience with racism in Canada and the way she handled it inspired me. Even though she feared how racism would treat me, her story is the only hope I carried. I always remember what she told me, “you will know. And what I faced, you will experience it. My experience is yours.”

The racism that I experienced began with my mother’s immigration to Canada. My mother immigrated to Canada in the early 1990s with the belief that Canada was a country of possibilities. From her point of view, she saw two paths: stay in China where the minimum wage could not provide a proper living or immigrate to Canada to seize opportunities. She chose Canada and believed that it would be a good time to immigrate. She saw Canada as her home — a home where colour does not and should not matter.

Her dream was shattered after a few days here. When she arrived in Vancouver, her assumptions about Canada and hope for an equal and better life were slowly destroyed. Anywhere outside of the safe haven of Chinatown, people targeted her with racist remarks and judged her with old stereotypes. She saw people making their eyes slanted, mocking her language, and calling her a communist. Even when she gave birth to me at St. Paul’s Hospital, she had to handle racism from nurses. After all she endured, my mother’s biggest fear still came true — the racism she has faced has been repeated in my lifetime.

I do not know how to fully describe the racism that I experience. I can only say that it feels like racism passes into the next generation and becomes a never-ending cycle. My first encounter with racism was in elementary school. My school advocated for inclusivity and diversity, which was awkward since more than half of my classmates were Asian-Canadian and all of the teachers were causcasian except for one who was Black.

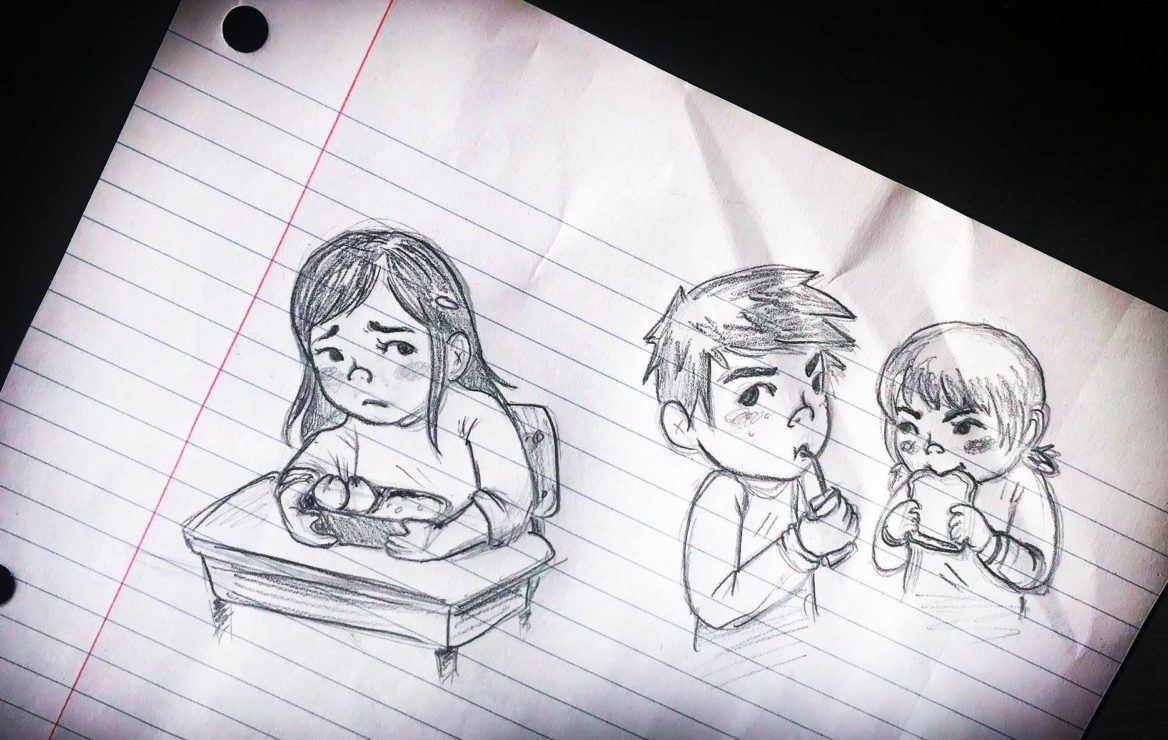

Beyond staffing, the school’s culture felt white-washed. For example, when it came to lunchtime, everyone had the typical lunch that you might imagine — sandwiches with a juice box. I did not have that type of lunch. Instead, I had fried rice or dumplings, which gave off a different smell than a sandwich does. My classmates would peer over my shoulder and look at my lunch. They wrinkled their noses, and pestered me with questions. Even my fellow Asian-Canadian classmates questioned me on why I couldn’t bring a “normal lunch” like everyone else. At that time, I felt ashamed and was often bullied by my classmates.

Moreover, old presumptions followed me. There are people who believe that Asians cheated the immigration system and live a lavish lifestyle. I remember the days when strangers would tell me to “go back to my country” or ask “why can’t you be like us?” Now, when I look back, I realize that racism flourishes differently in every generation while its fundamental character remains the same. In my generation, racism involves making racialized communities turn their backs on their culture and assimilating them into the concept of Western society.

Turning to the present day, racism continues to occur in my life. My experience is only one of countless stories. Since the beginning of the pandemic, people’s news feeds have been filled with reports on racism against BIPOC. There are reports that shed light on the harsh reality of what racialized communities face in Canada and the United States — countries that purport to be the homes of immigrants.

However, these reports only scratch the surface of what racialized people face on a daily basis. Daily racism encompasses more than shootings and police brutality, even though these happen more often than ever. The deaths of George Floyd, Rodney Levi, and many others should not be the only way to capture the public’s attention.

The smallest act of racism should be enough to raise attention in any environment. People need to know that the simple gesture of mocking someone’s mother tongue or calling the police when someone is rightfully in a supermarket is racist. It is a fact that any derogatory gesture towards someone of colour is racist. No one in this world can hide from that.