UVic Community Leaders are not naloxone trained despite being first point of contact in emergencies

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

*Names and identifying information have been altered to protect the privacy of those interviewed.

Aurelia, a UVic community leader (CL), joins the Martlet on Zoom from her dorm, where she lives and works as residence staff. She sits next to a window. The bright sky dims her image on the screen, appropriately reflecting the solemn tone of our conversation — and the considerable risk she has taken in speaking to the Martlet.

Following the tragic death of Sidney McIntyre-Starko, a first-year general sciences student at UVic who passed away in January due to fentanyl poisoning, many of UVic’s emailed communications with CLs regarding the incident included “CONFIDENTIAL” tagged in the subject line. As a result, CLs have been unsure what might happen should they share information regarding the incident, which occurred in residence.

Aurelia, Maxim, and Quinn have all been employed as CLs (live-in residence staff) at UVic for different lengths of time, in different residence buildings, and come from different walks of life. But they share a singular perspective following the tragic loss of Ms. McIntyre-Starko: the university should have trained CLs to administer naloxone — a drug which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose — years ago.

In a statement provided to Postmedia by UVic following Ms. McIntyre-Starko’s death, the university said that no time was wasted by Campus Security (CSEC) in giving McIntrye-Starko the help she needed during her overdose. However, records obtained by Ms. McIntyre-Starko’s family revealed that it took CSEC nine minutes before administering naloxone after arriving at the scene, and 12 minutes to initiate CPR — Ms. McIntyre-Starko’s family emphasizes that this delay is just one of the many failures on the university’s part in this tragedy.

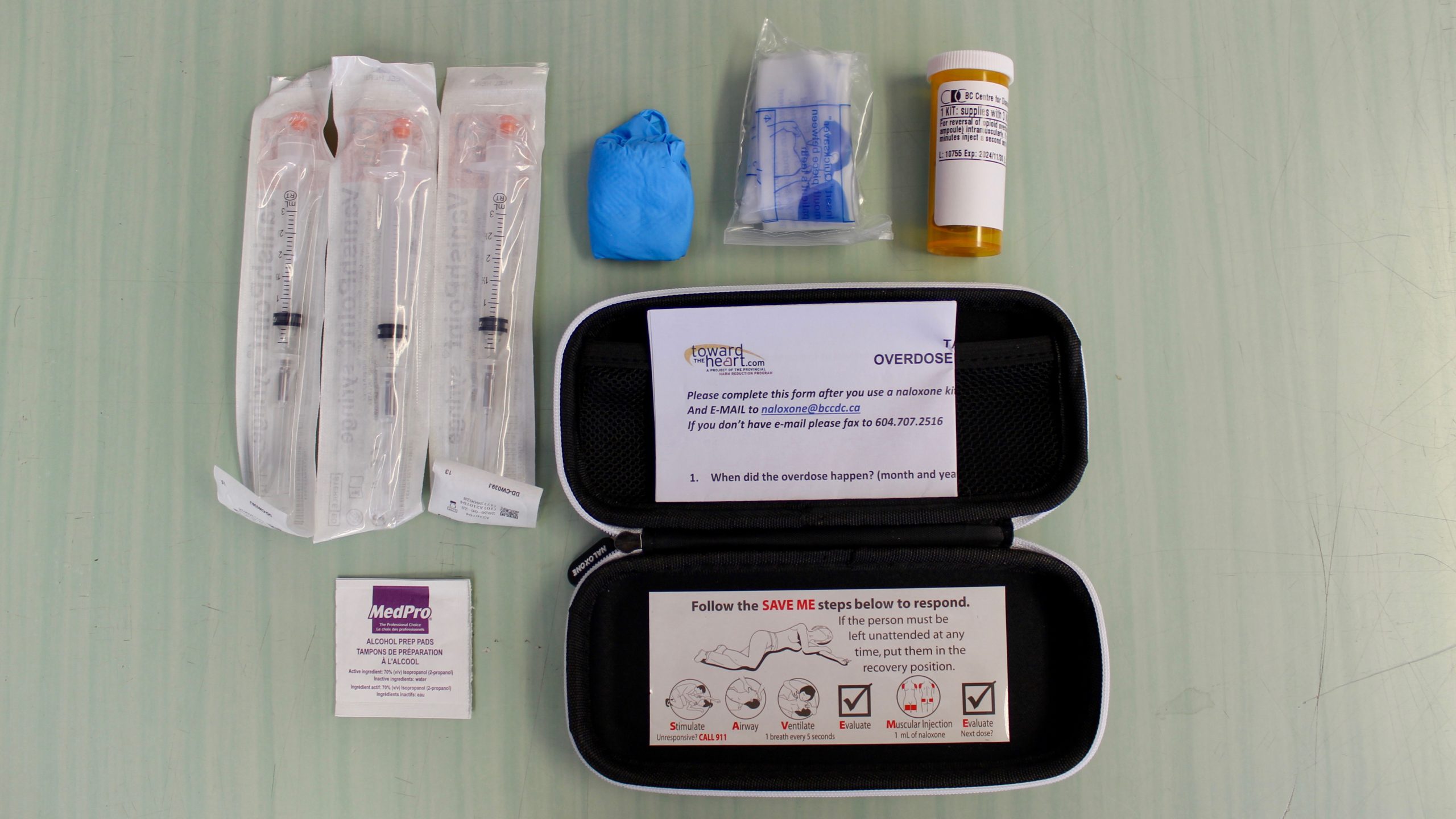

In the event of an opioid-related overdose, every second before naloxone administration counts. Additionally, there is little-to-no risk in giving the fast-acting drug, which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.

Statistics from the B.C. Coroner’s Service state that 26 people have died due to toxic drug overdoses on high school, college, or university campuses since 2016. The B.C. Coroner’s Service also states that Greater Victoria is one of three townships experiencing the highest number of unregulated drug deaths in B.C.

Toxic drugs are now the leading cause of unnatural youth deaths in B.C., and naloxone is one of the most valuable tools in treating a toxic drug overdose. In Ms. McIntrye-Starko’s honour, her family created a website which calls for province-wide changes to naloxone availability at university campuses to prevent another death like their daughter’s.

Lisa Beare, Minister of Post-Secondary Education and Future Skills, has announced, following the death of Ms. McIntyre-Starko, that B.C.’s 25 public post secondary institutions will roll out overdose prevention measures in fall 2024. Minister Beare says that general prevention measures will include more distribution and training for naloxone and posting naloxone in all resident buildings and high-traffic buildings.

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

In a statement to the Martlet, a UVic spokesperson says, “We continue to learn and adapt from the events of that tragic night and our policies and approaches are evolving accordingly. In addition to making improvements internally on campus, we are working with the B.C. government and other post-secondary institutes in B.C. to ensure there are systemic changes made that will help improve safety on university campuses throughout the province.”

More information about the university’s impending actions and policies will be revealed in the coming weeks, says the spokesperson.

What these prevention plans don’t account for, according to Aurelia, Maxim, and Quinn, is that CLs are often first responders in dormitory emergencies like overdoses, yet they are not procedurally trained on the administration of naloxone — and whether or not that will change come fall is still up in the air.

“CLs are on the front lines”

Residence staff have been requesting that UVic train them on how to give the overdose-reversal medication for years. “[But] we cannot push too hard. We fear losing our position. A lot of people rely on this position for housing,” says Aurelia.

“I just think it’s this real lack of recognition that CLs are on the front lines, and you need to give them the tools to be able to support students. That’s the job,” says Quinn.

A UVic spokesperson says, in an emailed statement to the Martlet, “UVic does not train CLs to assess someone’s medical condition; we emphasize that 911 and CSEC need to be called in medical emergencies.” CSEC Officers carry naloxone with them at all times while on shift.

Aurelia, Maxim, and Quinn corroborate this, saying that in their training that UVic instructs them to contact CSEC in the event of an overdose. They add that they are also explicitly instructed not to administer naloxone while on shift.

“I do have co-workers that are trained in naloxone independently, but we’re instructed it’s not our responsibility, and that’s something we’re supposed to call Campus Security to deal with,” says Aurelia. “We kind of just stand there.”

“We’re told that when a serious incident happens, your job is to call security,” adds Quinn.

In a written statement to the Martlet, a UVic spokesperson denies that this is instructed to CLs. “If a CL has first aid or naloxone training, they can administer naloxone as a private citizen under the Good Samaritan Act, but their role as a staff member is to always ensure they contact 911 and Campus Security in emergency situations.”

Before CLs enter their positions for the school year, they undergo two weeks of mandatory training that includes topics related to mental health awareness and how to file reports to Campus Security.

Notably absent from this training is a harm reduction module — including training on naloxone administration.

According to Aurelia, CLs have been requesting naloxone training from the university as a part of their mandatory occupational preparation since 2022. Allegedly, the answer from university staff has consistently been “No.”

To this, a UVic spokespersons says, “Exploring ways we can improve harm-reduction training for our CL community is part of the work we’re doing ahead of our August 2024 training sessions.”

Following the death of Ms. McIntyre-Starko, CL Charles Kjar created a petition for CLs to receive mandatory harm reduction training, including tools to handle “when a situation becomes a medical or safety emergency.”

“We cannot let the university sweep this under the rug, it is time for change. … We deserve to have the tools for dealing with any situation we may come upon,” says Kjar’s preamble to the petition.

The petition was sent to 100 CLs at UVic, and signed by 60; 100 per cent of whom answered that they wanted naloxone training.

The petition was not formally presented to Residence Services due to an exclusive bargaining clause in the agreement between UVic and The University of Victoria Educational Employees Union (CUPE 4163). However, due to interest from CLs in naloxone training following Ms. McIntyre-Starko’s overdose, the university promoted upcoming UVSS Safer Use training sessions for residence staff, and permitted CLs to use work time should they choose to attend.

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

Yet the optional training sessions conflicted with the class and work schedules of some CLs, and were intended for personal use — CLs were still not encouraged to administer naloxone as a part of their postings. “It was during the week during class time, so I couldn’t even make it,” said Maxim of the April training session.

Isabelle Easton, UVSS Director of Campaigns and Community Relations, explains that the UVSS has been facilitating frequent naloxone training workshops for members of the UVic community on campus since 2017. Easton says Residence Services didn’t contact the UVSS regarding the April 25 session. The session had 10 in attendance.

“UVic tries to act like those things don’t happen on campus, but they do, every single year,” says Aurelia. “We want more training. We want to be able to help.”

Residence staff at other universities trained to give naloxone

The B.C. Federation of Students, which represents students at 14 colleges, universities, and institutes, vouches for training and an increase in naloxone availability. Cole Reinbold, executive committee member, tells the Martlet, “The B.C. Federation of Students is proposing that naloxone kits be installed and clearly marked at accessible locations across campuses, wherever students would be [so that] everybody knows where to find them in an emergency.”

Mercedes Guerra, the Vice President of Human Resources at NaloxHome — an organization dedicated to harm reduction education — says that there are no health risks to administering naloxone to someone who is not actively overdosing.

“Naloxone only interacts with opioid receptors. So if there are no opioid receptors, there’s no opioid in your system, nothing really happens,” said Guerra. “[Opioid overdoses are] the leading cause of death,” they continue. “There’s always a way to make it safe for everybody.”

Many other Canadian universities have been leading by example — training their residence staff on naloxone use, and encouraging them to administer it in the event of an overdose. Institutions like the University of Alberta did so to prevent a death like Ms. McIntyre-Starko’s from happening on their campus.

Jared Larsen, former Students’ Union Vice-President at the University of Alberta, helped lead the implementation of the Residence Assistant (RA) naloxone training five years ago, in 2019.

“During my tenure with the Students’ Union, we worked with the University of Alberta Residence Services to ensure Residence Assistants were properly trained to administer the naloxone nasal spray,” reads a written statement provided to the Martlet by Larsen. “These initiatives arose as a precautionary measure with the opioid issues across Canada.”

At other universities across the country, including Vancouver Island University, Western, Carleton, the University of British Columbia and University of British Columbia Okanagan, Humber College, McGill, and Queen’s, residence staff are either trained on the administration of naloxone or permitted to administer it as a part of their posting. They either carry the drug with them or can access it in residence buildings.

Fletcher Thandi, a spokesperson for UBC, wrote to the Martlet that RAs in student housing on both of UBC’s campuses are given substance overdose training, which includes locating and using naloxone in student residences.

According to Humber College’s overdose procedure, the on-boarding of new residence life staff is not considered complete unless the staff have undergone naloxone training. Additionally, naloxone is stocked on all floors of residence buildings, at the front desk of each residence, with designated residence life staff, and a regular auditing system of these kits is in place.

At the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), residence staff all receive naloxone training and CPR training, according to a statement to the Martlet from a spokesperson. Additionally, RAs at UNBC carry naloxone kits in their bags when on call and are instructed to administer the drug when necessary.

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

For Maxim, this training is crucial at every university with student housing, because in their experience, when residents are confronted with an emergency situation, they come directly to the dorm room of their CL.

“These 18 year olds don’t know if they should call Campus Security, if they should call the police, who they should call. … CLs are meant to be there as a person in their building that they know and they trust, and they can go to and say, ‘This is the problem. I don’t know what to do,’” says Maxim.

“If we don’t have the capability to give naloxone,” he continues, “then we have to go through the steps of calling campus security and wondering if they’re going to administer it, or calling the police, and depending on how long it takes them to get there. It’s a lot easier to have someone who literally lives down the hall from you who can do that,” he says.

Harm reduction on campus

Though naloxone accessibility and training are crucial, many agree that a more comprehensive approach to harm reduction on university campuses is necessary.

“While we are dealing with this public health emergency … we just need to remind ourselves that it takes everybody’s work,” says Dr. Jaime Arredondo, Canadian Research Chair in Substance Use and Health Policy Research. And for Arredondo, harm reduction on university campuses needs to go beyond accessible naloxone kits and training.

For Maxim, harm reduction looks like drug testing sites on campus in addition to naloxone training.

Dr. Bruce Wallace, a scientist with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, says in a written statement to the Martlet that the benefits of drug checking on campus are “the same benefits as anywhere else, plus meeting students where they are at and when they most benefit from the information and connection.”

Wallace adds that while there are a number of options for drug testing — from fentanyl test strips to drop-off testing — an on-campus drug checking site where spectrometers and test strips are available would provide the greatest access and most timely service, although appropriate funding would also be needed to facilitate this.

Following the call to action from Ms. McIntyre Starko’s family, Minister Beare’s promise that post-secondary institutions will roll out overdose prevention measures in fall of 2024, and UVic’s statement that they will make changes to August residence staff training, it is still unclear whether naloxone training will be made mandatory for CLs, as these changes require consultation with the staff’s union, according to a UVic spokesperson.

Training residence staff on naloxone at Canadian universities is “absolutely vital,” says Reinbold, representing the B.C. Federation of Students. “Anybody who is on a university campus should be trained on naloxone, and the onus is on the institution to make that happen.”

“I am currently in conversation with CLs to discuss the best way to support them so they can get the naloxone training they want,” says Easton in an emailed statement to the Martlet.

While UVic CLs optimistically anticipate the potential of mandatory naloxone training in this year’s August orientation cycle, the dismissals of their resounding calls to action since 2022 cannot be forgotten, or forgiven.

Reflecting on the devastating loss of Ms. McIntyre-Starko, Aurelia says, “If we had had this training, I think things could have gone a lot differently.”