18 months in, UVic and campus community reflect on policy implementation

Photo by Belle White, Photo Editor.

The road to building a consistent, effective system for reporting sexualized violence at the University of Victoria has proven to be a long and bumpy ride, from the British Columbia provincial mandate that all universities would have such a policy till now.

18 months into the implementation of UVic’s Sexualized Violence Prevention and Response Policy (SVP), the university has reached another milestone: the first implementation review. As per provincial legislation, a one-year review is mandatory.

“[The review was about] the space between the lines of the policy, like how [we are] doing when it really comes down to it,” said Cassbreea Dewis, Acting Director of Equity and Human Rights (EQHR), who has overseen the SVP implementation since it began in May 2017.

“We couldn’t envision everything that would come, so [the review was] just to make sure that we do a really important self-check that we have been progressing well.”

Based on interviews with individuals across campus involved with the policy’s implementation, the review analyzed progress and challenges faced in the first year and laid out recommendations to further improve processes going forward. It was conducted in the fall of 2018 by a third-party consultant who is a former member of the working group on UBC’s sexualized violence policy.

The implementation review was declared confidential by the university, as the consultant used identifying details to justify some recommendations. However, the Martlet was granted access to a five-page executive summary of the review.

Although much of the summary was dedicated to outlining the challenges and recommendations for further improvement, it did feature the accomplishments of EQHR’s implementation so far. The summary mentioned the creation of brochures, operational forms, a sexualized violence prevention website, and workshops to facilitate the broader education and awareness of the policy on campus.

We’ve summarized the highlights below, and spoke with Dewis and other members of the university community about their perspectives on the review.

Consultation process

Over five days in the fall of 2018, the third-party consultant interviewed 45 individuals who had worked closely with the policy over the last year. Interviewees included administrators, respondents, survivors, in addition to individuals from Campus Security, Human Resources, Faculty Relations, the library, Media Relations, Athletics, the Anti-Violence Project (AVP), and all areas of Student Services.

Dewis initially said that EQHR decided to focus on consulting survivors who had just gone through the full report and investigation process.

According to statistics released by EQHR in May 2018, four formal reports had been made in the first year of implementation. In that time, there were 28 formal disclosures.

If what Dewis initially said is true, then only these four individuals were interviewed under the category of ‘survivors’ for the review. Later, however, Dewis reached out to clarify that some survivors who did not go through the entire formal report process may still have participated in the review. At time of writing, the number of survivors interviewed for the policy review is unclear.

“Awareness around the policy has definitely increased and it’s due to the work of EQHR that we’re able to provide our UVSS volunteers with bystander intervention training,” said Ainsley Kerr, Director of Campaigns and Community Relations for the UVic Students’ Society.

♦

“The university speaks and breathes in policy, and the Sexualized Violence Policy requires them to act in support of survivors and to demonstrate that in ways they previously did not.”

♦

Serena Bhandar, Community Relations Coordinator for AVP, regularly collaborates with EQHR. Although she says the policy does not heavily impact the work done by AVP, she feels it has made a positive impact on UVic — particularly at an administrative level.

“The university speaks and breathes in policy, and the Sexualized Violence Policy requires them to act in support of survivors and to demonstrate that in ways they previously did not,” Bhandar wrote in an email to the Martlet.

The executive summary states that everyone interviewed was “highly appreciative of the dedication and volume of work accomplished by the EQHR team.”

“Survivors/Complainants reported very positive experiences in the support they received,” the executive summary reads. “They appreciated the personal attention from the Coordinator and they felt validated and safe throughout the process.”

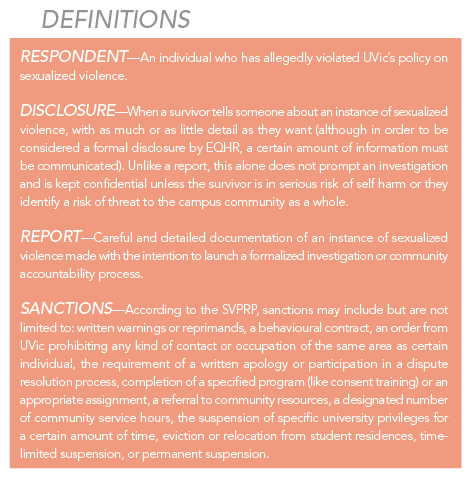

Definitions from the SVPRP via UVic

Not every individual who has experience assessing supports and reporting sexualized violence at UVic feels this way, however.

After reading the executive summary provided to her by the Martlet, Alex*, a student that previously shared with the Martlet her negative experiences at UVic with reporting sexualized violence, said the report fails to capture stories like hers of students who experienced inconsistent implementation of the SVP.

“This is the opposite of what I experienced,” she said. “I understand that there are many people with different experiences than mine, but I also think that this is a scenario where every single person deserves a positive experience in seeking support.”

Alex first contacted EQHR in early 2018 about improper confidentiality and support she had received at UVic. She never completed a full, formalized report.

She was initially told the review would begin in March 2018, and that she would be contacted when that occurred. The review did not begin until the fall, and Alex was never contacted throughout the process or told anything else about it.

“People are slipping through the cracks, and I don’t think they’re represented in this document,” said Alex. “The people who suffered from improper implementation of this policy last year are not spoken about — data collection and online modules are. It talks about how difficult it is for EQHR, for staff members in athletics and Res Life, even what case managers need. I could not find myself or my experience in this report.”

Challenges

There were five primary challenges of SVP implementation laid out in the executive summary. The first spoke to the difficulty in establishing the Sexualized Violence Intake Office in EHQR as the central point of support and contact about the policy.

Faculty members consulted in the review also noted that they do not see themselves reflected in the SVP’s outlined procedures and support systems — something Dewis hopes to pursue over the next year.

“What we want is for everyone to see themselves in the policy,” said Dewis. Faculty and staff can also seek support through the SVP, and she wants to ensure they are better aware of their options going forward.

Another challenge spoke to more effective procedures for respondents (individuals who are alleged to have violated the SVP) in receiving support going forward.

A majority of those who participated in the review stressed the need for additional resources in EQHR for intake, education, and support work being done. Currently, Dewis, who is the head of EQHR, and Leah Shumka, the Sexualized Violence Education and Prevention Coordinator, hold primary responsibility for most of the implementation work being done on campus.

One of the more detailed challenges spoke to the need for adjustments and clarity for the role of individuals working in UVic departments that have historically been most involved with responding to incidents of sexualized violence — Campus Security, Residence Services, and Student Life.

“As expected in any change process, this [new procedure] initially caused some resistance, which has diminished as working relationships have continued to evolve,” the executive report says.

♦

“The people who suffered from improper implementation of this policy last year are not spoken about — data collection and online modules are. I could not find myself or my experience in this report.”

♦

In areas of UVic that most frequently receive reports of sexualized violence — Residence Services, Athletics, and the library — young student staff members reportedly struggled with understanding their role in engaging survivors, consulting supervisors, and managing confidentiality, consent, and their own discomfort.

Through focused staff education, the report says “significant progress has been made and education will continue.”

The Martlet previously reported on issues with Resident Services’ response to disclosures of sexualized violence and the involvement of Campus Security.

For Alex, in the period after her experience with sexualized violence, interactions with a young Residence Services student staff member were times when she felt safe and validated. It was interactions with the older Residence Services staff members that she says were harmful to her.

“These experiences, which were consistently unpleasant, aren’t covered in this report,” said Alex.

Bhandar added that none of the recommendations spoke to the experiences of graduate students on campus, and the exploitation and abuse of power they can experience on campus.

Going forward, EQHR hopes to have a higher level of collaboration between EQHR and other units across campus to continue working on the consistency of UVic’s approach to sexualized violence education, prevention, and support. Dewis also talked about bringing this engagement beyond Ring Road and working with other universities.

“The collaboration doesn’t stop here,” Dewis said. “We need to be collaborating across the [university] sector as well.”

Recommendations for change

At the end of the executive summary, 13 recommendations are listed. Most speak to topics brought up earlier in the document; improving collaboration, inclusivity, procedures, and resources are all suggested, though the specificity of approach varies.

“I appreciated that they addressed some of the big, ongoing concerns with the implementation of the SVP, such as the capacity of the one-person office, …clarity and ease of access, … and the education of staff and faculty,” said Kerr, who works closely with the UVSS Peer Support Centre and their sexualized violence awareness initiatives.

One recommendation calls on UVic to create a “safe space for survivors to meet and continue to problem-solve around the issue of retraumatization of survivors when they see respondents on campus.”

While safe spaces currently exist on campus in different forms, such as AVP and the Peer Support Centre (both student-run), there is no current space of this kind run by UVic.

“All UVic community members should have a basic right to justice and a safe and accessible learning/working environment, and that includes safety from the trauma and triggers that survivors experience,” said Bhandar.

Over the coming months, EQHR will be considering the review’s recommendations.

“I think we need to do them in a priority order,” said Dewis. “[But] we need to consider them all.”

Apart from the recommendation regarding safe spaces, Alex felt the suggestions were vague and focused heavily on awareness and interdepartmental communications rather than directly supporting survivors.

♦

Moving forward, Dewis says she wants to explore other forms of addressing sexualized violence on campus, such as transformative justice and Indigenous forms of conflict-resolution.

♦

“I think it had to happen, but personally I also think it’s another bureaucratic step that is not solving the problems that exist,” she said.

Kerr agreed that voices of people most impacted by the policy could be better represented.

“[I] believe that survivors and people who have engaged with the policy on a personal level should be given the opportunity to present their own recommendations,” said Kerr.

Alex pointed out that the review mentions no Indigenous or other culturally-specific support options. She found this disappointing, having previously described how difficult it is to find sexualized violence support as an Indigenous woman at UVic.

“This is one thing that I desperately wish was accessible and well run,” Alex said.

Moving forward, Dewis says she wants to explore other forms of addressing sexualized violence on campus, such as transformative justice and Indigenous forms of conflict-resolution.

Both Kerr and Bhandar expressed that the EQHR office has conducted valuable awareness work on campus, and are interested in collaborating further.

As the SVP’s implementation continues to evolve, Dewis thinks it’s important for individuals to keep coming forward with feedback — whether it’s good, bad, or somewhere in between.

The next government-mandated review will take place in 2020, with further reviews every three years after that. In September, an updated statistical report on the implementation will be presented to the UVic Board of Governors.

EQHR will continue to reflect as implementation nears the end of its second year. Dewis understands that the path to a well-implemented sexualized violence policy is a difficult one, and cannot be properly navigated without a high level of collaboration and commitment.

*The name and some identifying information has been withheld to protect the anonymity of this individual