How one student’s experience demonstrates gaps in assault policy

The University Centre washrooms at the University of Victoria are among the last places most people would turn to for comfort, but Emma Cotterill found herself with nothing but dirtied porcelain to comfort her as she stood panicking about her situation. Despite being found guilty of sexual assault by the university, one of her rapists had won the right to keep living in UVic accommodation just a few hundred yards from Cotterill’s residence.

Over the past few months, Cotterill — a pseudonym due to privacy concerns — had been subjected to the arduous process that survivors of sexual assault must go through at UVic to report their crimes. She had spoken to lawyers, given countless recounts of her sexual assault, listened to her assailants’ statements, and waited for the verdict of her case — all while attempting to maintain grades within a full university course load.

Cotterill’s meetings took place in the ornate boardrooms of Judicial Affairs — the department in charge of investigating sexualized violence at UVic — and she rarely heard good news. In one such meeting, held in early March 2016, Cotterill learned that despite both of her assailants being ruled guilty of sexual assault, one of the attackers had won an appeal to stay in residence on the grounds that eviction was too harsh a punishment for the specific case.

John Derry, the manager of Judicial Affairs, asked Cotterill if she had any questions. She stood up, told Derry she was done with the meeting, and walked out of the office, heading straight for a bathroom.

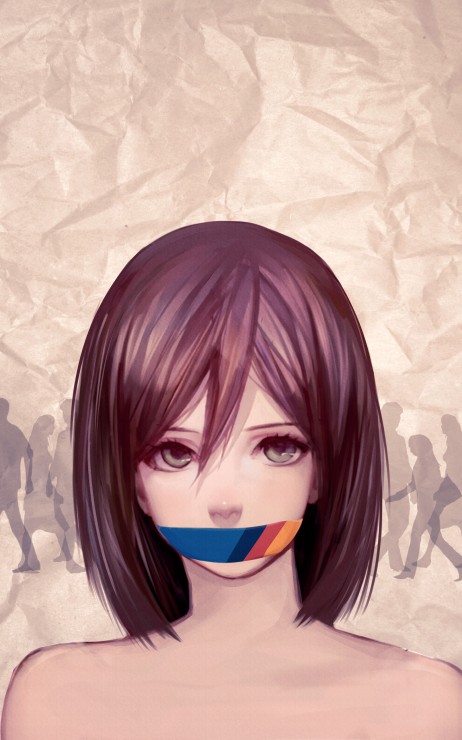

And there Cotterill stood, crying in the University Centre bathroom: furious, frightened and, above all else, alone.

[pullquote]

Over the past few weeks, numerous sexual assault survivors like Cotterill have spoken out about what they consider a lack of fair treatment by university administration.

[/pullquote]

Cotterill’s story might seem shocking, but it’s not unique. Over the past few weeks, numerous sexual assault survivors like Cotterill have spoken out about what they consider a lack of fair treatment by university administration. These survivors point to a lack of proper support during investigations, and sanctions they say favour assailants, not victims, as evidence that the university needs a drastic overhaul of sexual assault policies.

When I first meet Cotterill, she immediately strikes me as different from other survivors I spoke with. In stark contrast to the survivors and activists who speak passionately and eloquently about the institutional problems around sexualized violence at UVic and in our larger communities, Cotterill is a reserved figure, who speaks softly about her own experience while curled up on a couch, wrapped in a woolen blanket.

She isn’t someone who dedicates her time to educating others about sexualized violence — she doesn’t even know who Jian Ghomeshi is.

And, as Cotterill tells me, she hadn’t planned on reporting her own assault.

In late September of last year, Cotterill went to the Health Services office on the UVic campus to get medicine for a urinary tract infection. Her doctor asked her if she was sexually active, and Cotterill told her about being attacked by two fellow students just three days prior. The doctor recommended she report the attack to Judicial Affairs.

Judicial Affairs is a department of Student Affairs responsible for both academic and non-academic concerns at UVic. The department manages the Non-Academic Student Misconduct Policy, which pertains primarily to petty crimes like vandalism and theft, or health and safety risks like sexualized violence.

The policy dictates that all formal allegations — from theft to sexual assault — must be made within 10 university business days. Informal resolution is recommended, but, if that’s not possible, students can fill out an Incident Reporting Form to alert Judicial Affairs.

If Judicial Affairs begins an investigation, which consists of compiling statements from those involved, and confirming that misconduct has taken place, there are two types of sanctions — ‘minor sanctions’ or ‘major sanctions’. Minor sanctions range from apology letters to restricted access on university property, and major sanctions can consist of denying a student any access to UVic property, or suspending the student from academic privileges for a specified or indefinite amount of time.

The process is the same whether allegations consist of theft, disruptive behaviour, or sexual assault, and, with allegations heard on a case-to-case basis, sanctions are left completely to the discretion of the university.

The number of reported sexual assaults at UVic are unclear, as Campus Security is the only department at UVic required to publish the number of reports they receive. Counselling Services, Health Services, and Judicial Affairs all deal with students who have experienced sexual assault, but they are not required to disclose the number of students who come forward with those types of complaints.

As of January 2016, Campus Security had received 10 reports of sexual assault over the past five years. Considering UVic itself claims one in five female students are sexually assaulted while at university in Canada, the number is low, even when accounting for the large majority of students who don’t report their assault.

[pullquote]

As of January 2016, Campus Security had received 10 reports of sexual assault over the past five years. Considering UVic itself claims one in five female students are sexually assaulted while at university in Canada, the number is low.

[/pullquote]

The university maintains that employees in Health Services, Counselling Services, and Campus Security all encourage survivors of sexual assault to formally report to Judicial Affairs, as per the UVic doctor’s recommendation for Cotterill after her attack.

However, Lane Foster, a fifth-year student who was sexually assaulted in the fall of 2014, says the counsellor she saw following her attack did the exact opposite.

During an appointment with UVic’s Counselling Services following her assault, Foster alleges her counsellor advised her to leave the university and actively dissuaded her from formally reporting in favour of taking down her assailant’s name in case he was accused by another student.

“I felt alone, isolated, and insulted,” Foster says, saying that the counsellors blasé attitude raised a “red flag” and led her to think they had dealt with many similar cases.

The experience left Foster doubting if she truly had been attacked, and she did not formally report the crime.

“I don’t know if that was their job,” Foster says of the counsellor’s discouragement of formal reporting, “but if it was, it worked.”

Another survivor, who agreed to talk only under the condition of anonymity, said she faced a similar experience. When she told a doctor at UVic she had been assaulted, the survivor alleges the doctor shrugged and told her “it just happens.” She also alleges the doctor didn’t inform her of any other available resources for sexual assault survivors — as a result, the student did not formally report her sexual assault.

Foster does acknowledge that some doctors and counsellors have the right intentions, but that it’s not always the case.

“I’m sure there are plenty of great counsellors at UVic,” Foster says. “I’d like to meet them one day.”

Fortunately for Cotterill, she had the backing of her doctor; with that, and a desire to make sure her assailants couldn’t harm any more students, Cotterill was convinced to officially report her sexual assault to Judicial Affairs.

“I didn’t want those guys to do it to any other girls,” Cotterill says.

In early October 2015, Cotterill went into the Judicial Affairs office and gave her statement to Student Life Coordinator Kirsten McMenamie and a third-party lawyer trained in dealing with sexual assault cases. She sat through multiple interviews, seated opposite McMenamie and the lawyer, with no support to help her through reliving what had happened the night she was assaulted.

Next came waiting. Judicial Affairs began their investigation, interviewing the two students accused of sexual assault, as well as several witnesses. A few months had passed since her assault at this point, but without a decision made, Cotterill was left to try and continue her university career without any resolution at all.

On Dec. 8, McMenamie contacted Cotterill and asked her to come back in for another meeting.

It was in this meeting that Cotterill found out that her assailants had been found guilty of sexual assault. They were to serve several hours of community service, go through consent training, and be evicted from the university campus, where they had been living in residence. But, in a decision that bewildered Cotterill, she learned that that was the extent of their punishment. The university had recognized them as guilty of committing sexual assault, but had decided not to expel them.

When Cotterill asked Derry why that was, she alleges Derry told her they didn’t want the boys to commit a similar assault on another campus.

Despite this, Cotterill tried to see the positives.

“I was pretty happy with [the verdict], because I’ve heard pretty bad stuff about [survivor’s experiences where] nothing happens,” Cotterill says.

She spent the winter with her parents, finally able to tell them that she had been sexually assaulted. After three relaxing weeks spent with a supportive family, Cotterill boarded a plane to head back to Victoria, ready to start her second semester anew and get back to being a normal university student.

But just a few days into the semester, Cotterill realized her ordeal wasn’t over.

Cotterill was in her dormitory when she saw one of her assailants walking back towards his residence building. This, in itself, wasn’t unusual.

“I would always see him walking back in the direction of residence,” Cotterill says, “but I figured he was maybe going to a car, or to a bus. [But] I waited and actually saw him going back [into his residence].”

Carrying a McDonald’s meal and chatting with friends, Cotterill’s assailant walked back into his dormitory as if nothing had happened.

Panicking, Cotterill called Campus Security and informed them that her rapist was back in his residence. Campus Security, who Cotterill alleges were completely unaware that the student had been found guilty of sexual assault, went and investigated. They reported back minutes later and informed Cotterill that her attacker had appealed UVic’s decision and would be living in residence until the appeal had finished.

“I was so angry. I just started crying, and freaking out, because [Judicial Affairs] didn’t tell me that he appealed the decision,” Cotterill says.

Cotterill emailed Derry, who confirmed that the student had appealed the university’s decision before the winter break. Cotterill says Derry apologized for not letting her know, but said that he had been away on vacation and had been unable to inform her of the developments.

In emails and meetings sent and held throughout the first week of January, Cotterill learned that the university allows evicted students to remain on campus if they decide to appeal their sanctions. One of her assailants had decided not to appeal, and so remained off residence, but the other had appealed and was allowed to move back into his dormitory for the duration of the process.

The appeal process lasted for two months. In early March, Derry called Cotterill back in for a final meeting to discuss the results.

In the meeting, Cotterill says that Derry informed her that her assailant had won the appeal to downgrade from a major to a minor sanction. The university was not reversing the guilty verdict, but her assailant had successfully argued that a removal from residence was too severe of a punishment.

“They kept asking me, ‘how can we help now?’” Cotterill says. “I’m like, ‘how could you have helped these past six months?”

When asked for a response to Cotterill’s allegations, the university said they could not comment on individual cases due to confidentiality concerns, but Dunsdon, Associate Vice-President of Student Affairs, reiterated UVic’s commitment to reviewing policies.

“I would anticipate, and I don’t know, but I would anticipate that we’re going to be doing a thorough review of all our policies including Non-Academic Misconduct,” Dunsdon says.

But with no action convincing her that the university is willing to take the issue seriously, Cotterill says she most likely won’t be returning to UVic in the fall.

The mishandling of sexualized violence by university administrations is not a problem local to Victoria. Last January, the University of British Columbia apologized after it was revealed that the administration had taken a year and a half to respond to six separate complaints of sexual assault against a single student. On April 5, a survivor at Brandon University, Man., revealed the university had told her that she would be expelled unless she signed a gag order preventing her from talking about her assault.

[pullquote]

With no action convincing her that the university is willing to take the issue seriously, Cotterill says she most likely won’t be returning to UVic in the fall.

[/pullquote]

But things are starting to change. On Mar. 16, B.C. Premier Christy Clark promised to support a bill, introduced by Green Party MLA Andrew Weaver, requiring universities across the province to develop specific sexualized violence policies, similar to a bill that was passed in Ontario earlier that month. Just days later, UVic president Jamie Cassels released a statement calling sexualized violence a “serious issue”, and in a Board of Governor’s meeting on Mar. 30, Cassels announced that UVic had initiated a review of all policies regarding the handling of sexualized violence.

But for Cotterill, any change would be inadequate if it didn’t include an apology for past indiscretions. And so she is sharing her story, hoping UVic will be forced to recognize that both she and other survivors of sexual assault feel as though they have been abandoned by the very system they trusted when they were at their most vulnerable.

When Cotterill and I meet for our last interview, she’s carrying tissues and medicine for a sinus infection. Illnesses around exam season are nothing new for UVic students worn down by a year of school, but it’s clear that Cotterill’s year has been more taxing than most. We chat briefly before she says she has to get back to studying for final exams.

We say goodbye to one another, and she walks out of the interviewing room and down a hallway. Dwarfed by concrete walls on both sides and a monumental ordeal behind her, Cotterill is one of hundreds of women across Canada who couldn’t possibly feel more alone.