Now, the impetus falls on universities to pick up the slack on consent education

Illustration by Chloe Latour.

CW: This article discusses topics related to sexualized violence as well as transphobic and anti-LGBTQ2S+ messaging.

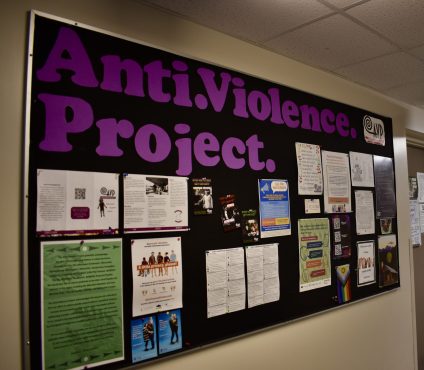

It is a Friday afternoon, three weeks after B.C.’s province-wide SOGI protests took place and a month into the fall semester. Carol Bilson ushers me into the Anti-Violence Project’s support room for our second meeting.

Last time we saw each other, we spoke about the university’s changing responsibility to educate their student body on consent in the wake of nation-wide sex education protests. The conversation was heavy then, and the weight of it remains in the air between us now, too.

The Anti-Violence Project (AVP) support room is a small office on the lower floor of UVic’s Student Union Building (SUB) that has been transformed with warm light, textiles, and houseplants into the closest thing to heaven that the basement of the SUB has to offer.

The AVP, a peer-run organization, focuses on ending gender-based and sexualized violence, providing support for survivors, and educating the UVic community about consent — and they are busy.

“As of tomorrow, we will be officially fully-staffed,” Bilson says, breathing a sigh of relief from the seat facing mine.

Just two weeks prior, Bilson was the only employee at the AVP, and she was feeling the pressure to staff the organization with volunteers for the fall semester, to prepare for what would inevitably be a season of incredible demand.

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), more than 50 per cent of college sexual assaults occur in the fall months. While this statistic is based on American research, Bilson confirms that she has seen the correlation between the fall season and higher-than-usual demand for sexualized violence services on UVic’s campus.

In autumn or otherwise, college campuses remain the most likely places in Canadian society for sexualized violence to occur, according to a report from Statistics Canada.

For Jennifer Gibson, coordinator of community education services at Island Sexual Health, the solution to the sexualized violence problem that runs rampant on university campuses is education around consent.

“Sexual health education is protective. It protects all people,” Gibson says through a Zoom screen. “Because consent is not a skill and a knowledge-base just for sexuality.”

Education around consent — which, as of November, 2022, is specifically articulated in the B.C. Physical Health Education (PHE) curriculum for students in kindergarten through grade 10 — informs all aspects of life, she continues.

According to Gibson, teaching consent means teaching critical thinking, agreement, and analysis.

“That’s essentially what consent skills are. We figure out, are we comfortable with something? Are we not? How much information do we need?”

However, concerned parents are resisting student participation in comprehensive sex ed, including consent education, after recent nation-wide moves toward sex and gender curriculum inclusivity.

Many parents in B.C. wish to remove their children from sex ed lessons and classrooms in the wake of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) resource integration in the PHE curriculum.

In other provinces, parents have reacted similarly because of efforts to implement curricular sex and gender inclusivity, such as Saskatchewan’s pronoun policy and an LGBTQ2S+ inclusive curriculum in New Brunswick.

Tracy Loffler, vice president of the BC School Trustees Association, explains in an interview with the Martlet that there is a misconception around sexual health education in B.C. that SOGI 123 is a “curriculum,” when they are actually a set of resources for educators that promote inclusivity.

Gibson calls this falsehood and other information that is being widely disseminated about SOGI across the country a “deliberate disinformation campaign,” which has accused educators of presenting an agenda as opposed to curriculum-sanctioned health information that is necessary for the wellness of all students.

Groups like ParentsVoiceBC, an organization that champions parents as school trustee candidates, disagree with Gibson, asserting on their website that their main purpose is to serve children in their educations and protect them from the indoctrination that occurs when parents are uninformed about what is being taught in the classroom.

They call for “wide-open transparency in curriculum and behavioural approaches,” and for school trustees to represent the parents and community of students, who play the primary role in educating their children.

The Martlet reached out to ParentsVoiceBC for further comment and did not hear back.

The 1 Million March 4 Children, held in various cities throughout Canada on Sept. 20, 2023, was a well-attended, organized show of disapproval for the inclusion of SOGI 123 resources in the PHE curriculum. A statement from their website says that their aim is to “safeguard the well-being and innocence of our children.”

Gibson resists allegations of indoctrination through an inclusive sex education model, saying that in reality, the idea behind SOGI-inclusive education is as simple as this:

“[If] you see yourself reflected in [the learning], that’s going to support you. If you don’t, it’s going to support someone else who does.” She continues, “I really struggle to understand where the risk is in creating more space for all people.”

In B.C., participation in PHE is mandatory, so there is no ‘opt-out’ option, per se, but parents can choose to arrange for alternative home delivery of certain topics related to sexuality or reproduction, so long as this is done in collaboration with the school to ensure that all curricular competencies are met.

In other provinces, however, it may soon be another story. In Saskatchewan, the government recently put forth a policy to make participation in sexual education optional for children, at the discretion of their guardians.

Another potential threat to sexual education occurred in New Brunswick, when national news saw allegations that the premier hoped to abolish sex ed altogether.

Gibson, as an educator, sees nothing wrong with parents choosing to deliver information around sexual education to their children by alternative means — so long as the decision is not made as a reaction to misinformation and is instead based on what is really being taught in the classroom.

However, the sheer amount of social traction beneath the wheels of anti-sex ed campaigns means that — regardless of what information their decisions are based on — parents in provinces across the country are vowing to pull their kids from sex ed in the wake of SOGI integrations.

“The first thing we do when we’re scared … is withdraw, right?” Gibson says of misinformation around sex ed resources and curricula. “We just pull away from it, we don’t want to participate in it.”

This calls into question the role that secondary school has in preparing students for the potential of a post-secondary education, where according to Bilson, a significant part of life is the introduction to (or dive further into) sexual relationships.

“We’ve got students coming [to UVic], needing that guidance because they’re walking into adulthood,” says Dr. Lyndze Harvey, an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at UVic.

University campuses like UVic’s are home to students from all provinces and all backgrounds. In 2021/2022, 34 per cent of UVic students were from outside B.C., including both out-of-province and international students. This means students are arriving with varying levels of knowledge around sexual education and consent.

Not to mention, Gibson points out, students may be coming to UVic from countries where sex ed is barred by law.

And ultimately, she is concerned that not all students from B.C. schools who have received an education around sex, sexuality, and consent are prepared to navigate sexual relationships in university.

“I would say about 75 per cent of [university students ask] very similar questions to what is being asked at the high school level,” she explains.

Students process the information that they are ready to hear when they are ready to hear it. For Gibson, this proves the importance of universities continuing education around consent and sexual health.

A 2023 report from LetsStopAIDS corroborates Gibson’s message, concluding that 63 per cent of young Canadians did not feel that sex ed classes prepared them for sex.

So, the question presses on: in a time when it is not guaranteed that students will have an understanding of consent by their first year at UVic, what is the responsibility of the university in consent education as a place where sexualized violence is statistically rampant?

In an email to the Martlet, a University of Victoria spokesperson addresses the fact that “UVic has an important role to play in the prevention of, and response to, sexualized violence on our campus.”

UVic offers two sexualized violence prevention workshops for undergraduate students at least once monthly. They also provide widespread consent education through online programs like Tools for Change and the Pre-Arrival Program, which educate new students about consent and healthy sexual decision making.

According to the most recent data from the Sexualized Violence Prevention (SVP) Consultation and Review — a 2022 report drafted by Aminah Malik from the Office of Student Life — 28.09 per cent of UVic students completed the Pre-Arrival Program and 1 016 residents began the Tools for Change module in 2021.

In an upcoming revision to Tools for Change, UVic will tailor the training for specific audiences in a move away from the program’s current universal model.

However, Harvey is concerned that even so, “the one time online approach [to consent education] is not effective, and it’s not enough.”

She clarifies that she doesn’t think the issue of ineffective messaging plagues UVic’s consent education efforts more than it does other universities. In fact, she says UVic is on par with, if not pulling slightly ahead of, other post-secondary institutions in terms of sexualized violence prevention efforts.

UVic’s Sexualized Violence Resource Office (SVRO) offers information around starting the consent conversation, resolution and investigative processes, and guidance for finding on and off-campus support.

For Harvey, though, what’s more important is the way that consent, as a conversation, is treated on campus — and the fact that the issue of sexualized violence often gets swept under the rug and doesn’t get spoken of nearly as much as it should.

“On the inside of the [bathroom] stall doors we’ve got ‘consent begins with a conversation,’ and these other taglines … but we’re missing something for sure.”

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

For Bilson, student demand for the AVP’s services is not only a stressor for the few staff at the project, but also an indicator of UVic’s failures to reach the entire student body with adequate consent education. This, according to Bilson, is a product of the way that universities in general handle the issue of sexualized violence.

The spokesperson from UVic writes that in the past five years, UVic’s Equity and Human Rights (EQHR) office has provided sexualized violence prevention and response education to 3 290 students and reached 700 members of the community with sexualized violence educational sessions.

However, the SVP Consultation and Review found that most surveyed students felt as though their peers who need to access an education around consent most — those who have no prior understanding of consent or its importance — are the people who would be least receptive to the online modules and least likely to participate in the voluntary workshops that UVic offers.

The report’s findings suggest that, in order to be thoroughly preventative, UVic’s approach to sexualized violence prevention must be more integrated than it is at present.

“[As] my dad would [say], ‘It’s gonna be in your soup!’” Bilson laughs.

The issue with UVic’s approach is that it’s a one-size-fits-all model, says Bilson. To really facilitate a culture of consent, the conversation has to permeate the physical classroom space and be acknowledged repeatedly and loudly.

Harvey corroborates this, noting that the sexualized violence policy and prevention information, although present in UVic course syllabi, fall to the end and likely go unread by most.

When Harvey spoke to me, she shared her experience seeing the backlash to an anti-date rape campaign at Queen’s University 21 years ago.

The campaign consisted of little yellow ribbons placed around campus everywhere a rape had been reported. Harvey says that as a first-year student, she was overwhelmed by the magnitude of the issue that the ribbons indicated.

“Then, I walked through the campus housing area on my way to class one morning and there were sheets hanging from windows that said things like ‘No means yes,’” she says.

Harvey believes that folks on UVic’s campus today would not tolerate that sort of behaviour, and she appreciates that since this incident in 2002, we have made progress toward safer campus cultures.

However, Harvey takes issue with the all-too-common messages that ‘we’ve come a long way’ and ‘things are better now than they once were.’

With the latest data from Statistics Canada in 2021 reporting the highest rates of sexualized violence in the country since 1996, it is evident that the problem — on campus and elsewhere — is as prevalent as ever.

“I think those are just terrible arguments. We deserved safety in 2002, and we deserve safety now,” Harvey says. “Clearly, we’re not doing what we need to be doing to make campus a safer place.”

And the need for adequate consent education, as far as Gibson is concerned, is only becoming more dire as parents and leaders resist and denounce sex ed.

According to Bilson, a majority of the onus to provide both education and sexualized violence prevention support systems at UVic falls to peer support services.

She explains that organizations like the Anti-Violence Project are usually staffed with marginalized folks who are disabled, racialized, or queer community members, who provide unpaid support because they know the impact of sexualized or other violence and hope to prevent it from happening to anyone else.

Bilson says she has often provided peer support for students who are facing waitlists for counselling through the Student Wellness Centre.

While wait times vary throughout the year, as of mid-October, the average wait time for a follow-up counseling appointment with Student Wellness is 12.7 days, according to a university spokesperson. For an intake consultation, the average wait is 15 days. Same-day urgent appointments are also available to students.

They also note that in the provincial and federal health systems at large, demand for staff is outweighing the current workforce, and UVic has also felt this stress — though they are putting in a concerted effort to hire and train more clinicians.

Still, Bilson says, longer wait times at Student Wellness services are a common reason why she sees students seek peer support instead.

“I feel like we’ve been … dumped the responsibility,” says Bilson. “It would be super if this wasn’t on the backs of the most vulnerable.”

She explains that a number of other universities have contacted the AVP to inquire about their work, and the project also sees departments at UVic reach out for support through the workshops that the AVP offers.

Bilson sees this as a huge success for the AVP — and a bright red flag for UVic.

“If you don’t want to have … a sexual[ized] violence issue on your campus, can we resource these things with more than two people for an entire campus?” Bilson asks. “That means we also have not just … two rooms in a basement, [where] students are supporting [each other] primarily.”

According to the UVic spokesperson, “the university does not rely on student organizations for this work, but [they] do support and work alongside them.”

While acknowledging the important role of UVSS advocacy groups in campus education, the spokesperson also highlights the fact that UVic bolsters ongoing efforts from the university itself in integrating sexualized violence prevention content throughout campus.

However, with statistics pointing to a persistent upward trend in instances of sexualized violence, occurring especially on university campuses, and a society in which sex and consent education is increasingly under fire, Bilson wonders what the hold up is in addressing the problem further.

In a perfect world, Gibson would see sexual education find its way into a continued, mandatory curriculum for university students.

Bilson thinks that consent and relational practice need to be addressed by professors in the same way that plagiarism concerns are — given more credence than they are at present and verbalized in the classroom repeatedly so that students understand that it is an issue the university and its faculty takes seriously.

“If you show up in class in your first year, you know what it means to have all your professors address something like that,” Bilson says.

UVic says that a number of faculty members have integrated SVRO content into their syllabi and “some put up slides in the first week of class pointing students to the supports available.”

Additionally, they say that UVic faculty are in regular contact with the SVRO about upcoming sexualized prevention workshops and tailored training sessions, to which faculty members have been “quite responsive.”

However, the surveyants of the 2022 SVP Consultation and Review largely felt as though there was still need for “SVP programming [to] be promoted and discussed in-person, in classrooms of all faculties.”

For Harvey, these approaches — which require instructors to take on the onus of communicating information about consent — would mean a complete overhaul of the system in which the University of Victoria exists and functions, since instructors are not trained educators, but experts in their respective fields.

This kind of overhaul would be almost impossible to reasonably achieve in the near future, as far as she sees it.

Instead, Harvey sees a solution for the too-quiet consent conversation in more peer support and outreach. She would call for peer mentors to come into each classroom every year and address the fact that sexualized violence exists, and will only stop if we talk about it openly and often — making the conversation unavoidable.

For this to be feasible, though, Harvey says that the university would need to allocate more funds to outreach.

In response, UVic emphasizes the results of a government survey on the effectiveness of the university’s current sexualized violence prevention efforts.

The survey about sexual violence on post-secondary campuses in B.C. found that UVic respondents felt that the training and education provided to them was “robust, diverse in topic and approach, and generally very effective.”

Still, Harvey is concerned that UVic’s conversation around sexualized violence prevention as it currently exists — largely contained in online modules, bathroom stall doors, and the end of syllabi — means continued and tangible consequences for the community.

“I really do think that if the university isn’t actively … walking their talk, then they’re supporting the status quo,” Harvey says. “And the status quo means that people are at risk.”

Bilson says that universities, as institutions, have a responsibility to be proactive about the issue of sexualized violence.

“Universities usually have a messaging about creating … the new civil society,” she says. “Well, that also means creating people who don’t harm each other.”

Carol Bilson. Photo by Sydney Lobe.

Bilson leans back in her chair when she says this. The small white speaker near the door of the AVP support room drones on. A seemingly endless instrumental track has been playing since I arrived.

I noticed it when we walked in because Bilson said, “Let me turn on my machine.” It was there to drown our conversation out to passers-by in the hall — another way the AVP has created a safe space for those who need it.

As I stand up to leave the support room that afternoon, I remember my conversation with Gibson about recent SOGI-inclusive sex ed protests when we spoke a few days earlier.

“I absolutely believe that in times of great change comes great resistance,” she had said, before adding, “and I think we are in that place right now.”

For Harvey, this resistance means pressure for universities to act, and be louder than ever when having the consent conversation.

Bilson and I stand in the doorway at the end of our interview, and after a bit of fussing with her machine, she turns it off.