Every year, thousands of tourists flood the Pacific Northwest for its renowned Douglas Fir and Garry Oak forests, mountainous landscapes, and the crisp, fresh ocean air gusting off the neighbouring Pacific Ocean.

For the second consecutive year, however, hundreds of wildfires burning across the province have forced the provincial government to issue a Provincial State of Emergency, raising concerns from professors that the hazy summers could become regular occurrences in the Pacific Northwest.

“My line for this summer is, ‘this is the new normal,’” UBC professor Michael Brauer told Vancouver-based magazine the Georgia Straight on Aug. 9. Alongside UBC associate-professor Chris Carlsten, Brauer co-wrote a chapter of the recently published book Reflections of Canada: Illuminating Our Opportunities and Challenges at 150+ Years about the deadly impact of poor air quality.

“We’re going to see more fire-smoke events like this.”

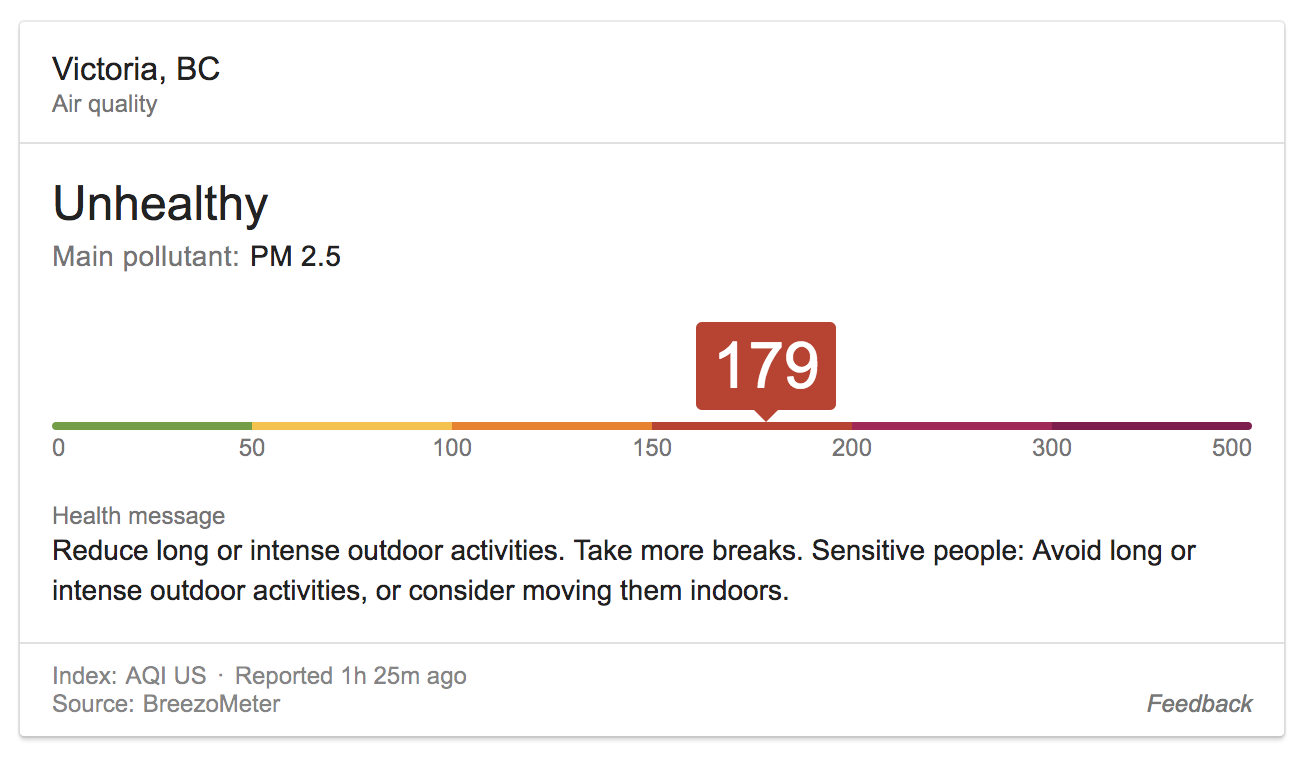

Victoria’s air quality, as of Aug. 22. The readings are more in line with cities like Mumbai and Shanghai. Data via BreezoMeter and Google

Brauer and Carlsten warned in the chapter that over 8 000 Canadians die every year in incidents related to air pollution, and that it causes more deaths annually than motor collisions, suicides, and HIV combined.

Although the majority of fires are burning in the northern and interior parts of the provinces, the changing wind patterns have floated the smoke down to the southern coast. The smoke has travelled as far as western Ontario, blanketing cities across the country with a yellowish haze.

The conditions are no different in Victoria, where Environmental Canada environmentalist Matt McDonald says it’s the epicentre for one of the world’s worst places for air quality.

“Vancouver Island’s definitely been flirting with some of the worst air quality readings in the world,” McDonald said in an interview with CTV.

On Monday, Victoria and Vancouver Island had a reading of 10 on the Air Quality Health Index, which records the area as a ‘very high’ health risk to the public.

The state of emergency last year stretched until Sept. 15, and this year, the province suggests that people should stay inside and refrain from strenuous outdoor activities if they are affected by the smoke.

2018 is the fourth-worst wildfire season on record, with still over a month to go.

While this degree of smoke is an unnatural occurrence, for thousands of years B.C.’s forests have gone through phases of increased fire activity, and they play an important role in the cycle of regeneration and regrowth of forests.

“Natural disturbances such as forest fires, insect and disease outbreaks, drought, wind throw and floods have occurred in Canada’s forests for thousands of years,” Natural Resources Canada writes on the Government of Canada’s website. “Disturbance is part of the natural life cycle of the forest and most often helps the forest to renew itself.”

In a Q&A last summer with the Social Sciences department, UVic geography PhD graduate and forest ecologist Jill Harvey echoed that sentiment.

Harvey said forest fires were commonplace in the Cariboo forest, a region spanning the central part of the province, and how a relatively recent stretch of low years of wildfire activity has provided fuel for fires today.

“Historically, many sites in the Cariboo forest region burned every 15 to 25 years between 1600 and 1900 AD. These fires consumed fine fuels and maintained open forests,” Harvey said.

But, Harvey continued, things have begun to change.

“In the last 100 years, very few of these sites recorded a single fire. Effective and widespread fire suppression has resulted in denser forests throughout much of the Cariboo, providing fuel for fires.”

Last year was known as one of the worst wildfire seasons in the history of B.C.; over 1.2 million hectares of land were scorched, forcing 65 000 people to be evacuated and costing the government over $568 million in costs to fight the flames.

As of Aug. 16, over 566 wildfires were burning across the province, scorching close to 400 000 hectares — making 2018 the fourth-worst wildfire season on record, with still over a month to go.