We apologize for interrupting your news. The following incidents and their consequences are by no means factual. What you are about to read is fictitious and disturbing. But it is not entirely untrue. We refer to these horrific events only as: the fables of the feces.

The first incident: a premature romance

West Hazel Maple Sage Gated Community, Suburbantown — Two beautiful people. One brisk spring evening. One fateful occurrence. Picture, if you can, the most attractive young couple you’ve ever seen: intelligent, well-dressed, bantering. They’ve just met, the two of them: a handsome man with a good haircut and a soccer player’s build, a young lady in a jogging outfit. And they know nothing about each other.

Perhaps she teaches at an elementary school and he works for the government. Or he sells real estate and she does graphic design. Maybe he drives a Mazda but would prefer an Audi, and she drives an SUV and sometimes feels bad about its carbon footprint.

They know nothing about each other. But on a lagoon of pavement in the back of a cul de sac gazed upon by four brick homes, they think they’re destined to be soulmates.

The interaction’s not all glamorous. She has a dog with her, her mother’s, which she walks weekly. It is aged and small and obstinate, and as the man meets the woman, she is scooping up a handful of its shit.

Good thing for plastic — perhaps he says something like this to her, and for a moment, they laugh. She is crouching on someone else’s lawn where her dog has defecated, talking to this hunk. He’s looking at this gorgeous girl with the incredible teeth and dog shit in her hand. It’s too perfect.

Their parents will ask how they met. To their friends they’ll say, “It was kind of shitty.” Their children, strapped in car seats in the back of a Land Rover, will tell one another about how mommy and daddy met over poo poo. To their grandkids, it will be legend. A story they hope someday to replicate; a lighthearted tale of the spontaneity of love.

But they know nothing about each other. Their thoughts are far ahead of them. Despite appearances, they have been unsuccessful at finding partners because of their respective narcissism. They are two lonely and insecure people with great imaginations. And none of what they dream of happening happens.

As she bags the steamy contents, flips the plastic inside out, ties the baggy with a double knot, and parts her lips to speak to the gentleman, the doggy bag explodes. And the man and the lady and the dog die.

The second incident: a boy on a tight leash. A martyr. An issue.

SUNNY PALACE PLAZA, Suburbantown — Lives are at stake. This shit is explosive. Unfortunately, it takes the death of little Robbie Ryan Jr. to acknowledge it.

He’s ripping home on his scooter after a visit to McDonald’s at the end of the school day with a pack of boys he calls friends. They’re way ahead of him, far down the sidewalk. He took too long getting out of the fast food restaurant.

After paying for his McFlurry (his first ever transaction without his mother), Robbie Ryan Jr. was left with an awkward amount of change — too much for his Velcro wallet. And so he opted to do one last philanthropic deed. Penny by penny, quarter by quarter, to the kids whose parents can’t afford to raise them in good homes, Robbie Ryan Jr. donated $2.37.

He’s hotfooting down the sidewalk, this boy who grew up literally on a leash. At home waits a plate of chocolate chip cookies. He tries not to think of them. He tries to focus solely on catching up with the boys he calls friends. They’re the same age as him, but somehow seem bigger and meaner and cooler. Puberty hasn’t happened to Robbie Ryan Jr. yet. But puberty could happen to him anytime, he thinks.

He lugs a backpack, but not a helmet. This is the first day Robbie Ryan Jr.’s mother hasn’t picked him up from school; he wants to be cool.

He shouts after the boys he calls friends, but they don’t stop. He tears down the concrete, whipping his left foot against the pavement, using his right for balance — and hits a bump.

He’s offered to the air in the shape of a starfish. But he doesn’t fall onto the pavement. Doesn’t skin his knees or shear his palms of skin or his hands of fingerprints. Because he’s not wearing a helmet, and his mother has told him that when falling he should aim for the grass, he does just that. He is a dangerously obedient boy. And he lands, headfirst, on a pile of dog shit.

This time there are witnesses: the boys Robbie Ryan Jr. calls friends, halfway across the street; a car full of girls getting smoothies after volleyball practice; a clerk gazing longingly through the gas station window; a jogging octogenarian, training for her triathlon (she’s blown backward by the pillar of flame, cement and feces that reaches for the clouds).

A scooter flies out from the towering grey miasma and clatters on the sidewalk.

Something is wrong with Suburbantown’s shit.

McSad Day

COMMUNITY HALL, Suburbantown — A vigil is held at a grassless, dog-less venue for Robbie Ryan Jr. and the couple that never was.

The dangers of the feces become known. Upon contact with certain people, the dog shit of Suburbantown explodes. And it is their shit. And it is their problem. Still, citizens are wary of confronting it.

The townsfolk retreat. Children are given the option to stay home from school. Shops close. Flags are set to half-mast. Home Depot sells out of plywood; homeowners board up windows. Families buy deep freezers and canned foods.

Soccer games become nightmares and are soon banned. It is too much to think that because of something smelly in any little divot left by a cleat, a child and his or her shin pads could be blasted to oblivion.

Landscapers and lawn mowers are put out of work entirely. Mailmen and mailwomen’s pay increases. They’re informed of the hazards in their workplace, briefed on how to efficiently and safely navigate the neighbourhood. It’s best to avoid sod.

A park that once teemed with dogs and their masters is now desolate. There is only the sound of crickets chirping at night. There are no more Frisbees. There are no more barks. No one risks visiting any public space that could be a minefield of dog shit.

Bagging and handling is too dangerous. The less human contact the shit comes into, the less likely it is to explode. Dog owners put pads of paper product in the corners of their kitchens and never dispose of the soiled ones — just keep adding new paper on top of old. Newspaper sales peak, but not because they’re being read. As do the sales of leashes, but not for dogs, for children. If Robbie Ryan Jr. had still been on his, he wouldn’t have met the end he did.

Mothers exhaust their maternal creative genius to keep their young indoors to avoid the shit. When they are done with the finger paint and the origami, it’s on to the board games. And when they are done with the board games, it’s on to the video games. And when they are done with the video games, anxious children ask for permission to go outside, forcing mothers to refuse and state how generous they’ve been, how much extra Outside Time they’ve already allowed.

An angry Samaritan, who could have helped with cleanup but instead became a self-preserving hermit, has attached a sign to a street lamp typed in Comic Sans that reads: CLEAN UP YOUR DOG SHIT, I DO NOT WANT TO DIE.

He later explodes during a lonesome picnic on a promontory that, unbeknownst to him, was favoured by a St. Bernard named Michael.

The origins of the stink

BIOHAZARDOUS FACILITY, Suburbantown — Government-employed biochemists are unable to successfully analyze the feces. The origins of its deadly properties remain a mystery.

“I understand there are many citizens who want to hold someone responsible, who want to believe that there is one person who’s been poisoning our canines or that there is one dog in particular that is sick, diseased. But that’s just not the case,” says Dr. Lincoln Horwitz, Chief Fecal Analyst.

“What makes it so explosive? What makes it ignite?” Horwitz asks after testing the stool of a golden retriever. He removes his Hazmat suit, washes his hands thoroughly, brushes his teeth and flosses. “We don’t know,” he says. “What we do know now is it’s not the varying quality of the — excuse me — shit itself. It’s not like a collie’s is more likely to explode than a Rottweiler’s. What we’re finding is it’s the circumstance of the contact. It’s certain people. Certain environments. It can go off at any time, but only if particular outside factors are present. And this is something we’ve got to deal with carefully. This sickness is exclusive to Suburbantown. This toxicity was created here.”

Dirty bombs

SUBURBANTOWN APARTMENTS, Suburbantown — In smaller living arrangements, the stench of a dog’s accumulated waste is unbearable. One slothful citizen, unable to stomach the odour that permeates his kitchen, balls up the newspaper containing his dog’s feces and flushes it down his toilet only to cause an explosion of unprecedented consequence.

On its descent, the wad of feces blasts through the infrastructure of six floors, through drywall, through plywood and brick. The shit destroys the very foundation of countless homes.

A government-sanctioned plan for dog detainment ensues. Here, it’s reasoned, are living, breathing weapons that don’t fire bullets or rockets, but rather, hunch, pucker and release a deadly substance, daily.

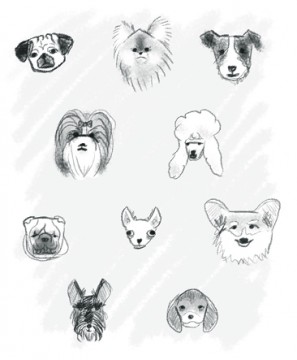

Dressed in Hazmat suits, equipped with collars, leashes, muzzles, cages and catch poles, Feces Control Agents kick in the doors of suburban homes. Families of four sitting on couches with popcorn bowls on their laps lose their kernels and watch helplessly as the FCAs tranquilize basset hounds, chocolate labs and chihuahuas and drag them across squeaky wooden floors, disappearing them.

There are also reports of the FCA striking at night, of little girls waking in the morning to eat their Cheerios and find that their furry friends are gone from the porch steps.

Under the FCA, virtually all canines are removed from Suburbantown to biohazardous facilities. But a few remain. Pet enthusiasts do what they can to hide their dogs beneath mattresses or in closets, attics, garages and underground.

Bad dogs

EAST HAZEL MAPLE SAGE COMMUNITY, Suburbantown — Righteous citizens like Humphrey Diddlehurst seek the underground dogs out. He and other vigilantes proclaim themselves saviours of the town. Their mandate is simple: to let the citizenry know of the canines that surround them.

Before he leaves his home to conduct business, Diddlehurst “pumps up” to the Baha Men’s “Who Let the Dogs Out.” With a flashlight, night-vision goggles and sometimes a balaclava, Diddlehurst — former Suburbantown High quarterback and Suburbantown Arm Wrestling Champ five years in a row — scours his neighbourhood lawns for any signs of canine life: chew toys, bones, dog bowls. He takes his time, tiptoeing from property to property. His life, he says, is at stake every night. One careless step through a flowerbed, one hasty trot through a front yard — and boom!

After a successful mission, in the comfort of his man cave, Diddlehurst cracks a Red Bull and his knuckles and updates a digital map, an online satellite view of Suburbantown he’s tweaked to feature flashing red dots, the presumed locations of rogue canines.

“Everyone should have the right to this information,” he says. “This is the digital age.”

By day, he knocks on doors to inform and question citizens. “Do you know a Yorkshire terrier lives next door?” “Are you aware a pug lives across the street?” “Has it occurred to you that there are not just one, but three poodles within a five-mile radius of your home?”

Diddlehurst died last Thursday while attempting a citizen’s arrest on a Shih Tzu.

finallY: dialogue

UPSTANDING CITIZEN COMMUNITY HALL, Suburbantown — Another death. Another vigil. Fewer attendees.

“When will this come to an end?” Dr. Horwitz asks. “I can’t say. You’d think we could have put it behind us by now. But we never forget. The stink persists. This was and is a complicated substance we’re talking about, with all kinds of things that set it off. But it’s important we remember it exploded here in Suburbantown, because of us.”

“Hogwash,” Robbie Ryan Jr.’s mother states. “That we are in any way culpable for the events that have transpired is hogwash.”

“This is healthy,” Horwitz says. “This right here — it’s healthy. Conversation. Dialogue. Openness. It’s time we take accountability. It’s time we cease being reluctant to talk about it because it makes us feel disgusting. It’s time we talk about our shit.”

But Horwitz acknowledges such conversation can become insular. “The other night before bed, while I was watching TV, I said to my wife, ‘Hunny, have you seen these poor kids in Somalia and the land mines? Have you seen them?’ ”

“And she just turned to me in an outrage. ‘How am I supposed to be watching the news?’ She asked me. ‘How am I supposed to be watching the news when I’m so worried about our own shit?’ ”