hen a whale dies, it usually slips quietly away from view. Some sink to the bottom of the ocean, to be slowly consumed by species lower on the food chain. Others might float for a while as gas builds up in their distended bellies from decomposition. Their bodies are hardly ever recovered, but in early December, a dead orca called J-32, carrying a near full-term fetus, was towed ashore.

hen a whale dies, it usually slips quietly away from view. Some sink to the bottom of the ocean, to be slowly consumed by species lower on the food chain. Others might float for a while as gas builds up in their distended bellies from decomposition. Their bodies are hardly ever recovered, but in early December, a dead orca called J-32, carrying a near full-term fetus, was towed ashore.

Today, J-32’s bones are on Saltspring Island, buried in compost and soil. Her remains are being cleaned of remaining soft tissue so they can be displayed some day at the Royal BC Museum. Her calf’s remains are in a freezer at the museum, waiting to be examined. Scientists have been able to analyze every part of the whale and her calf, all except for four missing teeth in her jaw, the result of looters seeking personal souvenirs or trinkets to sell.

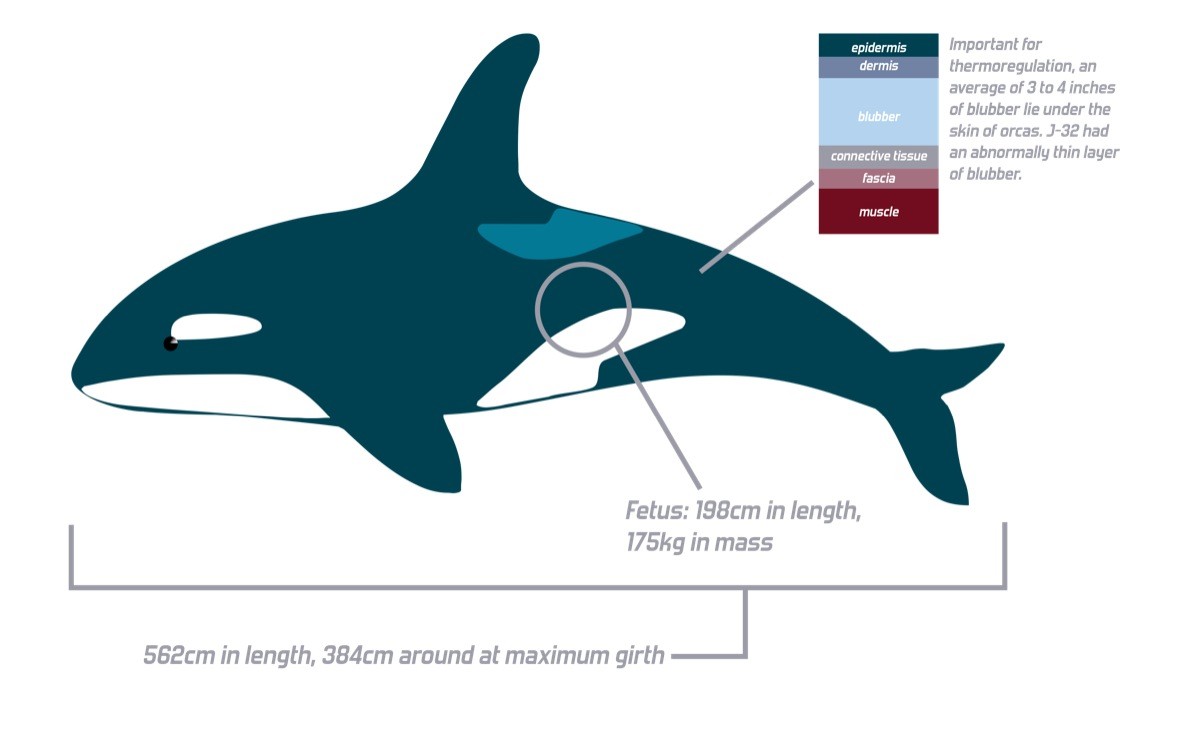

On Bates Beach that morning, the orca looked out of place. A body meant for swimming sat on its side instead, perfectly still on a wrinkled blue tarp. Her tongue lolled out of her mouth, bloody gaps where teeth should have been. A flipper pointed towards an overcast sky. Though J-32, known as Rhapsody, wasn’t the biggest killer whale (she measured a fairly average 18 feet long), the 40-odd people who watched the necropsy looked like Lilliputians beside her.

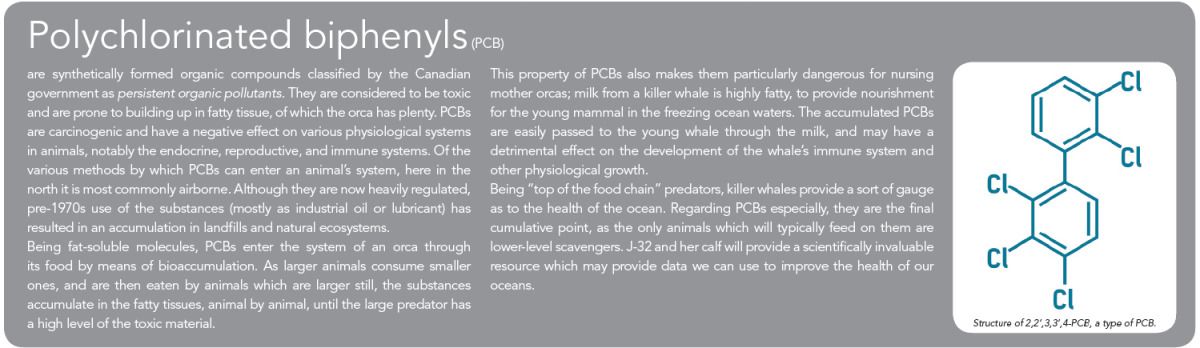

The remains of the whale have been shipped off to eight laboratories in Canada and the US to determine its condition, but Peter Ross, a toxicologist with the Vancouver Aquarium, doesn’t expect to be surprised by the results. Past studies already confirm that our southern resident orcas are highly contaminated with hormone-like PCBs and other toxins that suppress their immune system. Noise pollution from ships and sonar interfere with their calls, disorienting them in the already murky depths. Chinook salmon stocks threatened by overfishing, climate change, or pollutants force the residents to swim farther to feed themselves.

“These animals are long-lived, top of the food chain, and if they’re not doing well, they are potentially reminding us that we’ve got work to do,” says Ross.

In February 2014, Ross was hired by the Vancouver Aquarium as director of its Ocean Pollution Research Program. He was given samples of J-32 and her fetus that his lab will test for contaminants. It will take 4–6 months to complete the analysis, but a preliminary report from Stephen Raverty, the DFO pathologist who performed the necropsy, attributed J-32’s death to a systemic infection from the calf’s death in utero. Prior studies done by Ross and other scientists showed that PCBs can change the expression of five genes that affect growth and development, adversely affecting an orca’s immune and reproductive systems, which may have weakened J-32’s ability to fight off pathogens, bacteria, or other environmental stresses.

Ross worked for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) as a toxicologist until 2012, when the DFO scaled back its research into marine contaminants due to budget cuts by the federal government. Opting instead to offload such research to universities and independent facilities, the DFO closed its Sidney, B.C. lab along with others across the country. In a Times Colonist interview that year, Ross expressed his concern, saying, “It is with apprehension that I ponder a Canada without any research or monitoring capacity for pollution in our three oceans, or any ability to manage its impacts on commercial fish stocks, traditional foods to over 300 000 aboriginal people, and marine wildlife.” To continue the research that the DFO has scaled back, the Aquarium built a new lab for Ross and his new team, and is partly funding research along with other grants that Ross seeks. He said that “It’s hard to lose a job and lose a laboratory,” but he was happy that the Aquarium provided the support necessary to continue his work.

Before the necropsy began, Harold Joe, a filmmaker and member of the Cowichan tribes, addressed the small crowd. He knelt down by the whale’s head, her heart, and the fetus, with an eagle feather in his left hand and burning herbs in his right. Surrounded by smoke, he encouraged mother and calf into the spirit world, cleansing them after death. The crowd was invited to sprinkle crushed cedar to accompany their prayers and good wishes. When the smudging ceremony was finished, she was measured, and the necropsy began.

Michelle Rachel, a UVic student and volunteer with CETUS (an orca conservation and outreach organization) learned of J-32’s death when her Facebook news feed became populated with posts claiming a whale had been found ashore.

“My first thought was, ‘Well, it’s so far north that it has to be either a transient orca, which is the mammal-hunting one, and we have hundreds of those, or one of the northern residents, which are not nearly as endangered as the southern residents.’ So while you never want to hope that it’s a certain type, you definitely hope it’s not a southern resident.”

Thinking it would be a learning opportunity for the inevitable crowd, she emailed the CETUS director of communications and education, Leah Thorpe, asking if there was anyone from the group attending the necropsy. One member would try to make it, Thorpe replied, but Thorpe encouraged Rachel to go. After a three hour drive, Rachel arrived around 11 p.m. on Friday night.

“It was cold. It was a full moon, but there was a huge rainstorm so there was no light whatsoever, and it was almost hailing. The tide was out, so the rocks were really slippery as we were going over to the beach, and there were a couple of guys walking along the beach with a flashlight, ‘cause it was pitch black. And I said, ‘Do you know the whereabouts of this whale?’ And they pointed up there, and sure enough there was this big black mass, and it was unmistakable.”

Rachel’s interest began after a trip to Hawaii, where she frequently encountered humpback whales. After returning to Victoria, she felt compelled to try and help. She spent this past summer on an inflatable boat, talking to recreational boaters about the federal guidelines surrounding whale watching and reminding them to keep their distance and cut their engines if whales are present. The program, known as Straitwatch, has been run by CETUS since 2005, but according to Thorpe, its funding has been cut drastically by Environment Canada, with little explanation.

Rachel’s interest began after a trip to Hawaii, where she frequently encountered humpback whales. After returning to Victoria, she felt compelled to try and help. She spent this past summer on an inflatable boat, talking to recreational boaters about the federal guidelines surrounding whale watching and reminding them to keep their distance and cut their engines if whales are present. The program, known as Straitwatch, has been run by CETUS since 2005, but according to Thorpe, its funding has been cut drastically by Environment Canada, with little explanation.

In the past, CETUS has relied on Environment Canada’s Habitat Stewardship program, which according to Environment Canada’s website, “allocates between $9 and $13-million a year to projects that conserve and protect species at risk and their habitats.” In 2011, the group got $320 000 from the program. Though they expected the same amount the following year, they only received $100 000. In an email, Thorpe said that she didn’t know about the funding reduction until the end of the summer, after the summer programs were complete and the funds were spent. In 2013, CETUS got nothing, and so the Straitwatch program did not run. Last year, it received $35 000, about a tenth of their previous funding. Currently, CETUS is piecing together smaller grants and donations from public and private entities to fund their programs, but for Thorpe, it is an imperfect solution.

“Getting that large chunk of funding from a single source definitely makes our lives easier in terms of how much time we’re spending administering the grant,” said Thorpe. She said that due to the reduced funding, CETUS has had to “piece together quite a few other grants, which of course drastically ups our admin time.” This year, they are requesting $180 000 from the federal government, hoping to continue its Straitwatch program in full, instead of the scaled-back program that ran in 2014.

The necropsy took the entire morning. Clad in yellow coveralls, the pathology team began by making cross-sections of the whale, peeling back blubber and skin and measuring for thickness. Her blubber layer was thin—according to Ross, a sick whale loses its appetite, relying on its blubber reserves to carry it to recovery. When the pathologists opened her abdomen, Rachel heard a high-pitched squeal as gas that built up during decomposition escaped. She said it reminded her of the sound an orca makes when it is in distress.

Marcie Callewaert, a Grade 6 teacher in the Ahousaht First Nation (north of Tofino), also learned of J-32’s death from a Facebook post. In her childhood, she was fascinated by orcas, re-enacting a scene from Free Willy by trucking her stuffed whale to a pretend ocean with Lego, but her interest grew after seeing them as a teenager.

“It was when I was 14 and I saw them way off in this bay when I was camping,” she said. “And they were tiny pinpricks for me, but it was amazing, and that was when it really clicked seeing them in the wild.”

On the car ride over, Callewaert tried to keep herself occupied, but the reason for her trip was in the back of her mind. She had seen Rhapsody in the past, alive and with her family members. While on the water, Rachel saw Rhapsody often as she was an exuberant whale, breaching frequently in view of human spectators.

Back at school, Callewaert’s students were naturally curious about the whale, given their proximity and the cultural significance of the animal. She told them about the necropsy and answered their questions, but elected not to show them any photos.

During the dissection, chinook salmon bones were found in the whale’s stomach, as expected. While transient orcas eat a variety of marine mammals (seals, sea lions, etc.), southern residents are pickier eaters. A healthy southern resident orca consumes 100–150 kg of chinook salmon each day, which comprises over 90 per cent of its diet. The salmon are large and high in fat, which makes them an ideal choice, but since the southern residents live and feed near populated areas, they absorb chemicals through their prey, which bio-accumulate over their long lifetime (the oldest known orca, J-2, or Granny, is estimated to be 103). When mothers give birth, they pass toxins on to their calves through their fat-rich milk (orca milk is 35 per cent milk fat, whereas dairy cows produce milk with only 3.25 per cent fat content).

A 2009 journal article by DFO scientists and the Center for Whale Research indicated that the number of killer whales in the region were strongly correlated to the availability of chinook salmon. While the killer whale population grew between 1974 (the first year the whales were counted) and the mid-1990s, both northern and southern resident orcas “experienced a period of unusually high mortalities in the late 1990s,” two–three times the expected rate.

“The salmon on the BC coast has always been a problem,” says Josh McInnes, a UVic grad and member of the Transient Killer Whale Research Project, an independent research group. His research group, supported by private donors and organizations such as the Oak Bay Marine Group (which lets them use their boats for free), keeps an eye on the transient population, which he says has been spotted more and more, while resident sightings have decreased.

From a research perspective, McInnes says that while there are many active groups in Canada that research the southern resident orcas, more could be done. “It seems like the United States is doing most of the work, while in Canada there’s been a little bit of a slowdown.”

The Transient Killer Whale Research Project has attracted interest from individuals on the island, but also interest from as far as Sri Lanka. Their Facebook group is just one of many groups that are dedicated to orcas. The movement to “save the whales” has been prevalent since the environmental movement gained traction in the mid-1960s. Like elephants and dolphins, orcas are seen as intelligent, and even exhibit human characteristics like mourning (female orcas have been seen carrying dead calves on their heads for hours on end).

Gavin Hanke, the curator of vertebrate zoology at the Royal BC Museum, understands the public’s fascination with orcas, but warns that such a narrow focus can sometimes mask a greater environmental challenge.

“If we want southern resident killer whales to persist, we can’t just focus on the whales,” he said. “We’ve got to focus on habitat [and] food base.”

As Ross notes, actions that preserve the killer whale population have wider-ranging effects for coastal food webs.

“Flip it around. If we can help protect and nurture this population in a way that makes their future viable and healthy, then we are very likely to have done the same for hundreds of different species in the Salish Sea, from chinook salmon, to forage fish, to the near-shore vegetation.”

Orcas are a symbol of the west coast, and drive millions of dollars into the provincial economy, most directly through whale-watching tours. They are a crucial part of coastal First Nations cultures. Saving them requires securing their food and their habitat, but whales are not the only beneficiaries of such actions. In addition to feeding the southern resident orcas, securing chinook salmon stocks will support commercial fishers.

After months in soil, J-32’s bones will leave Saltspring Island smelling like a pine forest. They will be stored in the Royal B.C. Museum’s research tower until they can be displayed. Hanke hopes that the remains will be displayed in a new wing of the museum dedicated to the Pacific Ocean and its inhabitants. After J-32’s death, there were 77 orcas left among the southern residents. Her calf, a female, would have provided a needed population boost. But just before the year ended, a new calf was spotted, its sex unknown. It may not survive infancy, but it won’t be for lack of trying. Teeth marks on the calf’s body suggest that it was pulled out of its mother by another whale acting as a midwife.