The course rating system opens the door to biases, cyberbullying, and systemic discrimination

Graphic by Sage Blackwell.

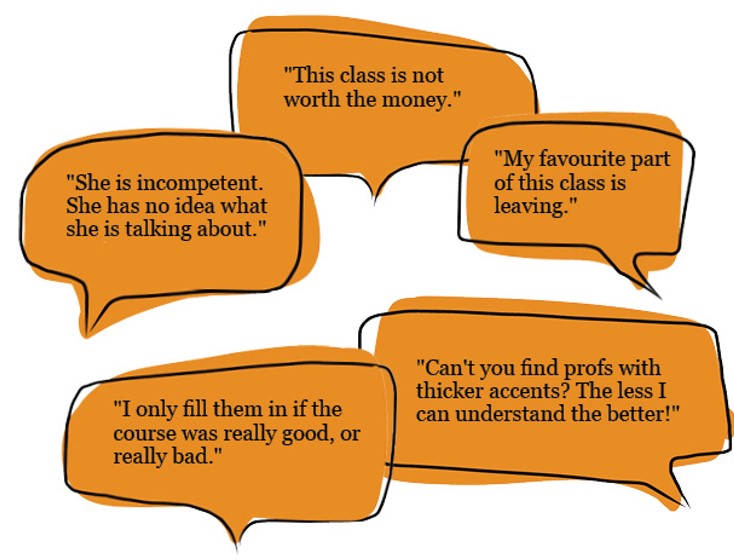

When a semester comes to an end, students and professors alike drown in assignments. While academic performance is measured by instructors throughout the term, exam season opens an avenue for students to provide critical feedback on their instructor. For some students, this is payback time.

As former UVic sociology instructor Tucker Farris reviews his Course Experience Surveys (CES), an online survey with a number of questions and fields for feedback answered by students, he notices that the clump of entries offers little to no constructive feedback. Nothing out of the ordinary, he thinks, as he scrolls through the positive reviews that claim they wouldn’t change a thing and the negative ones that say they dislike the course — no feedback on how to improve as an instructor yet. Then, a review makes him stop. Filled with hate and disregard for his person, this review ends with by stating that Farris’ class was not worth the money.

Farris would leave UVic shortly after reading this comment.

A science instructor at UVic, who wished to remain anonymous, gives his partner access to the Course Experience Survey entries first. She filters the reviews that attack him. “I don’t yet have a thick enough skin to take them and not be hurt and demotivated,” he wrote in a Reddit post. “And I am in the ‘privileged’ category (white, cismale, hetero). It’s worse for others.” He opted not to comment further because his position is not tenured.

Dr. Christine Sy, Associate Professor of Gender Studies at UVic, and an Indigenous professor from the Makwa Odoodem (bear clan) from Obiishkikaang Lac Seul First Nation in northwestern Ontario, was asked to review her CES to reassess her January salary evaluation. In them, she would find some of the most hurtful comments to her person, and no constructive criticism on how to improve her lectures. Of the most hurtful comments, Sy asks, “How is this supposed to be helpful?”

Dr. Lynelle Yutani, President of the Camosun College Faculty Association (CCFA), says of her Japanese heritage, “I have been fortunate that … I’m more white-passing, so I don’t experience as much of the anti-Asian racism in the instructor critique.” She continues,“However, I’ve had colleagues who … have more discernable racialized identities, who have students being absolutely horrid about accents.”

This type of comment is not new. Studies have consistently noted biased, sexist, racist, and other discriminatory remarks in CES or other forms of feedback since their implementation in post-secondary education. CES misuse poses systemic challenges to faculty job security and access to tenure across Canadian post-secondary education because they are inappropriately used by admin to determine re-hire, pay wages and tenure. So what is their purpose in academia? And if they’re so bad, what’s the alternative?

Many postsecondary institutions across Canada use a form of CES. Although methods differ, most use a point-based system of review with opportunities for students to comment anonymously. These surveys were developed in the 1920s at the University of Washington and Purdue University, Indiana, by educational psychologist Herman H. Remmers and psychologist Edwing R. Guthrie, who wanted to develop a system that provided information to professors on how students assessed their teaching and thus help instructors modify and improve their teaching skills.

Guthrie and Remmers, prioritizing personal improvement, intended for these course evaluations to be read by professors only. This limited access was rejected by administrators shortly after the implementation of these surveys, even though Guthrie warned in 1953 that while helpful to improve one’s teaching, CES cannot establish absolute degrees of merit. In his 1953 article titled “The Evaluation of Teaching”, Guthrie wrote that CES are a way to measure the “student’s reaction to teaching. … It would be a serious misuse of this information to accept it as the ultimate measure of merit.” Despite Guthrie’s warnings, university administrators continue to use CES to award prestige and promotions to instructors.

“The feedback gathered … helps the departments assess an instructor for the means of providing merit, promotion and re-appointment,” wrote a UVic spokesperson in an email to the Martlet. This seems to be true at the University of Waterloo, the University of British Columbia (UBC), the University of Saskatchewan (USASK), and the University of Toronto (U of T) too. According to the University of Toronto’s website, students are encouraged to complete the surveys because “Chairs and Deans rely on [student] feedback to make changes to your programs and degree requirements. They also use feedback for tenure, review, and promotion decisions.”

The Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) declined to comment on the function of CES.

Some students find CES to be a valuable tool for providing feedback on their learning experience. “CES allow students to provide feedback for further generations of students,” said Eric Willis, a 2024 UVic alumni. CES are one of the only ways a student can let a university know that an instructor needs improvement without issuing a formal complaint. “I take the evaluations seriously in hopes that the professors do too,” said Eric.

However, based on many online posts, most students seem to fall into one of two extremes: only filing out CES if their course experience was great or horrible.

Dr. Jamie Sewell, assistant teaching professor at the University of Victoria and former instructor for the University of Waterloo said CES, “end up perpetuating the same kind of thing we see on Yelp or Google reviews. Those students who are really in love with the course take time to do the course evaluations, and students who are really pissed off by their experience in the course [do, too]. So we get this really extreme set of responses, rather than a broad overview. ”

These disparate responses reflect the lack of participation from the student population in general. Simon Fraser University has observed a lower response rate to CES post-pandemic. In Montreal, McGill University’s rate fell over 10 per cent between the 2017/18 and 2022/23 academic years.

Photo by Fernanda Solorza.

Many universities have experienced a decline in CES response rates in recent years. While the pandemic likely contributed to this trend, the decline began with the shift from paper to online evaluations. A Journal of Educational Informatics study published in 2021 through Ontario Tech University noted that CES done on paper typically resulted in response rates of 80 per cent or higher.

In contrast, electronic evaluation methods often result in response rates between 30-50 per cent. After transitioning from paper to digital, McGill’s response rate dropped to 42 percent and only returned to a normal rate of 51 percent after several years. “[Online surveys are] great because it enables greater accessibility. But, we tend to get way less information, because fewer students are doing it,” said Dr. Sewell.

This lack of participation in surveys rarely translates into constructive feedback. Dr. Sewell said that when she was a newer instructor, she felt confused and, at times, infuriated by her comments. “Why are all these students so focused on whether I’m nice or not, instead of focusing on whether I’m organized or accessible or competent?”

“Even very well-intentioned student trying to fill out glowing reviews … fall into … gendered language use.” She continued to explain that a student saying she’s a good instructor because she partakes in certain gendered roles, such as emotional labour, doesn’t reflect the quality of the course nor does it give her feedback on how to teach better.

A 2021 Journal of Academic Ethics study showcased that a professor’s identity and faculty can become undisclosed biases for students filling out CES.

A 2023 study performed by the UK Higher Education Journal showed that 59 per cent of participating academics reported receiving abusive comments in their student evaluations in the early 2020s; however, this abuse is not evenly spread across different demographic groups. Women academics and those from marginalized and racialized backgrounds receive more negative comments than their straight white male counterparts.

Dr. Patrick von Aderkas, Treasurer of the University of Victoria Faculty Association, who has been at UVic for 35 years, wrote in an email to the Martlet that the successful use of course evaluation wavers. “Generally, [course evaluations] are fairly useless for the following reasons: low student response rate, well-documented bias against women and BIPOC faculty to name just two groups, hateful/hurtful comments, a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t take into account specialized teaching approaches and media use.”

Dr. Aderkas continued, “On the other side, if a prof gets nothing but unalloyed praise, they are bound to use or even emphasize their CES scores in their teaching dossier, as university administrators are obsessed with metrics.”

A science professor at UBC wrote an extensive Reddit post in 2021 titled “Teaching evaluations: the good, the bad, and the ugly.” In this post, he presents his experience with CES and that of one of his colleagues. He recounts how his colleague taught two sections of the same course during the same term; the two sections were even on the same day, but at different times, and garnered his colleague two vastly different sets of reviews.

He theorized that the more accessible time placement contributed to the one course receiving better reviews than the other; he also suggests that the former had better “student quality,” as students with a higher GPA may register for courses sooner, and thus naturally choose the less-stressful time placement.

“So that is one concerning piece,” he wrote. “These scores seem fairly random, and yet they are scrutinized with fine-toothed precision when important decisions are made.”

Dr. Georgia Sitara, Assistant Teaching Professor in the Gender Studies and History faculty at UVic, winner of the 2020 & 2019 Most Valuable Professor Award, the 2019 Gilian Sherwin Alumni Award for Teaching Excellence, and the 2017 Faculty of Humanities Award for Teaching Excellence, explains that excellent teaching requires an instructor to tailor their approach to the class they have in front of them. It is not possible to be a great teacher and never change.

Dr. Sitara has been teaching since 2001. “It’s been a pleasure to be part of the academic journey of so many students,” she said in an over-the-phone interview. “I was there when the surveys were done by hand, and there’s been a change through the generations of students. … In the past I could assign weekly reading as well as writing assignments. This is no longer possible. I recognize that students’ capacity these days has shifted, so I adapt to them. Students are the future, we need to set them up for success,” she says with a chuckle. “But that doesn’t mean I’ll go easy on them.”

While CES responses are not publicly available, Dr. Sitara’s reviews on the website Rate My Professors showcase many positive reviews, while emphasizing the difficulty of her course. “The level of respect they expect from me as I grade their papers is the same level of respect I expect from them as they evaluate my teaching,” she said.

“Of course, I still get the occasional bad review, usually from someone who didn’t do as well in their grade as they expected. That has become the newest issue. There is a correlation between students’ satisfaction with their grades and how they evaluate me. I don’t think that’s fair.”

UVic does not provide statistical reports on the correlation between students’ final grades and their evaluations via the CES. This lack of information overlooks a significant factor that can strongly influence how instructors are assessed. Sewell pointed out that while she worked at the University of Waterloo, CES requested students to indicate their expected grades when completing the survey.

While students remain anonymous, this practice offers further insight into how to interpret the comments provided for the class and instructor, assuming the students provide truthful information. “Students can, if they like, input an expected grade that well represents their actual expectations,” said Dr. Sewell. “Or they could opt to include a value that isn’t realistic, and the instructor can’t really be sure which it is.”

Universities other than UVic, such as UBC or U of T, have developed different resources for students to provide constructive feedback on their courses, but any reports on the success of the resources are not publicly available. Similar to UVic, these other universities ask students to be respectful, constructive, specific, and thoughtful.

A UVic spokesperson said in an email, “If survey results include abusive comments, instructors are encouraged to speak with their chair and/or Associate Dean, Academic and/or their union group.” When the Martlet asked the UVic Faculty Association how UVic deals with discrimination and cyberbullying in CES, Dr. Aderkas, a representative, answered, “It doesn’t. At all.”

Dr. Aderkas explained that faculty can choose how they use CES scores in teaching dossiers, focusing on pedagogy and innovation rather than relying solely on survey results. Teaching dossiers are documents that show administration how a professor approaches teaching, their goals, and how they’ve improved or innovated. This includes which courses they’ve taught and how they’ve helped students. Professors can focus their teaching dossiers on their teaching methods when they show them to administration, rather than showing the CES scores, which they might not think accurately represent their teaching quality.

“A professor could actually provide evidence of applications of pedagogy, as opposed to the results of a poorly designed blunt survey tool, that is, CES scores.”

Many instructors articulated their concerns about the commodification of education and the pervasive “consumer mentality” in students. Dr. Sewell said, “[CES are] not actually to ensure that people are excellent instructors. I think it’s to ensure that however students want to be made happy, we do that, because students keep the lights on.” According to interviewed professors, students are becoming more entitled to get a “good experience” at university, which usually means receiving high grades in exchange for the cost of their degree.

Professor Farris, who claims to have left UVic for several reasons, including harmful comments, entitled students, and low wages, said, “[CES] actually created some trauma around teaching for me.” He said that whenever he missed class for sickness or was late grading papers, he had an impending sense of guilt, since he wasn’t performing to the best of his customer service abilities. He was incredibly apologetic for things that were not his fault. “Once a majority of the students see you as a customer service employee that they’re paying for a service, it’s over,” he says.

All these systemic issues surrounding CES demonstrate there is a deeper problem within UVic and perhaps academia. Although universities and administrators try to develop better ways to evaluate instructors’ teaching proficiency, the reality is that “administration is constantly having to tinker with this very broken tool,” said Dr. Aderkas. “CES scores are a rearview mirror that rewards stasis and sometimes even punishes teaching innovation.”