While not eligible for housing spots, community has come forward to provide guests with everything from tents to restaurant gift cards

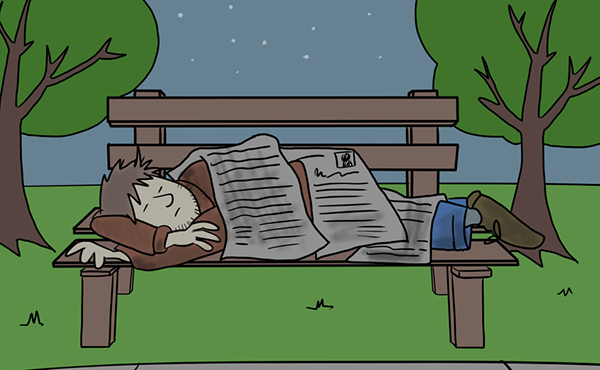

On July 1, the Victoria Native Friendship Centre’s seasonal shelter was forced to close — sending visitors back onto the street, including eight to 10 regular guests.

These guests were considered “housed” by BC Housing during the rush to provide spaces for those camping at Topaz Park and on Pandora Avenue. As such, they are not eligible for any new rooms that have opened up in hotels or motels. The Victoria community has stepped up to furnish them with everything from tarps to restaurant gift cards.

Besides proving to be an exercise in community, the shelter’s closure also serves to return the spotlight to homelessness amongst Victoria’s Indigenous community.

The 25-bed shelter, which usually operates from November through March, was able to stay open for three additional months due to extra funding provided by the BC Housing Management Commission. The decision to keep the shelter open longer came with the onset of COVID-19 and the necessity of making sure that all those who had the option to shelter in place could do so. Unfortunately, with funds running out, the shelter was forced to make preparations for closure last month, and while they tried to get their guests spots in other shelters, they were ultimately unsuccessful.

While the closure of the shelter has proven to be positive in the sense that it has galvanized the community, the shelter’s guests are still left without a place to go. In an interview with CBC, Rice revealed that one former guest died of an overdose just 30 hours after the closure, while another was killed from an incident of violence nine to 10 days later.

“[Staff] reached out to all the shelters to find out who had beds, the challenge of course being that with all of the social distancing requirements from public health, a number of beds have been eliminated from the system and a shortage of staff have meant some other shelters have had to close,” said Ron Rice, the Executive Director of the Victoria Native Friendship Centre in an interview with the Martlet.

With the provision of housing for their guests no longer an option, the shelter’s staff switched their focus to ensuring their guests had enough supplies to make the transition to the street.

“We were doing our best to sort of outfit [our guests] with things that could sort of help them through this transition if they weren’t moving on to other shelters,” explained Rice.

To further help their guests, shelter manager Kalynka Cherkosh put out a call on Facebook on June 29, asking the Victoria community for donations or any outdoor camping gear they might have such as tents, tarps, and sleeping bags. She also said that any donations of restaurant gift cards would be greatly appreciated.

Just a few days later on July 3, Cherkosh edited her post stating that since her original call for donations the shelter had received over $1 000 in donations not only from Victoria, and the Gulf Islands, but also from as far away as France and the Galapagos Islands.

In the updated post, Cherkosh expressed her gratitude for the community’s support. She had been hoping to give each guest one or two items, but thanks to the donations was able to give them much more than that.

Each guest was able to receive a new light rain jacket, as well as gift cards for restaurants, coffee shops, grocery stores, clothing stores, and fast food establishments. They also received their choice of antibiotic cream, mouth gel, sunscreen, flashlights, blankets, tarps, backpacks, tents, and sleeping bags.

Rice also said that he has told staff to keep in contact with as many guests as possible and to provide them with food if they would like and are able to find a place to stay.

“We have let [guests] know that if they do find a place to be we can continue to deliver food through our food hamper program,” Rice said. “We are keeping on two of the staff to fill other positions and I’ve told them to make sure people still have your contact information if there’s anything they need … we will be there.”

While the closure of the shelter has proven to be positive in the sense that it has galvanized the community, the shelter’s guests are still left without a place to go. It has shone a light on the problems facing Indigenous communities who are disproportionately represented amongst Victoria’s unhoused community.

A 2018 Point-in-Point Homeless count estimated that one third of Victoria’s unhoused community are Indigenous, despite Greater Victoria’s Indigenous community only making up five per cent of the area’s total population. Rice says that this might even be an understatement.

“In terms of the population itself, those numbers are skewed depending on which reports you look at and what weight you put behind the responses, but it’s probably somewhere between a third and 40 or 45 per cent,” Rice said. He also allowed that at any given point around 50 per cent of the shelter’s guests are Indigenous.

For Rice, the crisis of Indigenous homelessness can be traced back to intergenerational trauma and the residential school system.

“The ‘why’ is very complicated and can probably be boiled down to the ongoing, intergenerational trauma from the Indian residential school system and the Sixties Scoop,” Rice said. “Everything can be traced back to that — whether it’s parenting, or low-education success, or underemployment, or domestic violence.

Olvie Li is a nurse who spent around five years in an Anishinaabe community working for a First Nations Health Centre. While being clear that she cannot speak for those with lived experiences of homelessness, she discussed how the crisis of Indigenous homelessness can also be traced to colonization and the dispossession of land which resulted in the Indian Act and the construction of reserves.

“I found that a lot of my friends, community members … who whenever they leave the [reserve], whenever they leave the community, they are usually on the streets, and that’s because the reserve has been set up so that you don’t get out of it and when you do get out of it you don’t really survive because there’s no systems that support you off reserve,” Li said.

Li also emphasised the stigma that Indigenous people face off of reserve, particularly when they are on the streets.

“I know that back home [Indigenous people] are just regular community members, but out here they are seen as just another homeless person, or drunk, or whatever,” Li said.

Despite the challenges facing Indigenous people in Victoria and across Canada, Rice is hopeful for the future. He emphasised the work of the Victoria Native Friendship Centre as well as other friendship centres across the country which are doing lots of work to help members of Indigenous communities get the support they need, including applying for post-secondary education or for a mortgage.

“Although we’re often dealing with crises and that’s what makes the news, there is a lot of success happening for our people,” said Rice.

This article was updated to include information regarding the deaths of two former guests of the Victoria Native Friendship Centre’s seasonal shelter.