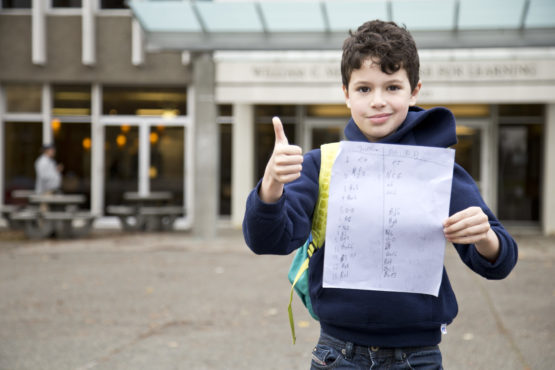

Meet nine-year-old Jose Rodriguez who’s already completed pre-calculus 11 and is probably smarter than you

All photos by Belle White, Photo Editor.

Jose Miguel Valdes Rodriguez sprints through the plexiglass doors into the dimly lit Esquimalt Recreation Centre’s main foyer with an ear to ear grin on his face, tugging his mother’s coat on the way.

“I neeeed my notebook mom! He’s going to ask me, and I need something to write with,” Jose says, dragging out every last ‘e’ to plead his case.

His wavy brown hair is still damp from swim practice, and a few spots of water are visible on his burgundy and gold ‘Mathlete All-Star’ shirt.

Cynthia, his mother, smiles and brushes off her son’s complaint. She takes a seat and hauls Jose’s overstuffed red backpack onto a table. Jose, for the time being, forgets about his notebook conundrum and begins to unpack textbooks and Rubik’s Cubes with the ferocity of a child tearing at wrapping paper on Christmas morning.

Despite being only nine years old … Jose has the moxie of a performer or conductor.

His chestnut-coloured eyes, infectious smile, and enthusiastic voice liven up the suspiciously dark lobby. A couple of nearby children stray from their parents to catch a glimpse of what all the commotion is about on this otherwise quiet Friday evening.

“Those are cool Rubik’s Cubes!” another child says of Jose’s three differently shaped cubes.

Ernó Rubik, the Hungarian inventor of the first 3-D Rubik’s Cube some 40 years ago, would be proud of Jose’s collection. Along with the classic version, Jose has another in the shape of a pyramid (called a Pyraminx, Jose tells me later) along with a multi-tiered one that looks like a miniature building designed by a modern architect.

Despite being only nine years old, and not being able to talk or communicate until the age of three, Jose has the moxie of a performer or conductor.

He doesn’t sit down. Instead, he waves his hands in excurberant motions, asking “so, what do you want me to do first?”

A MEMORABLE MIND

Jose was diagnosed with autism at three and a half. When he was finally able to talk, Cynthia found that he could read and write extraordinarily well, and that his memory capacity was that of someone twice his age.

Cynthia insists it was a toy mat that ignited his memory and desire to learn.

“We discovered his memory [a few] months before he was diagnosed with autism,” she says. “We bought a mat for him, those mats that have different squares with different colours, and have letters and numbers,” she says.

When Jose was three, Cynthia and her husband watched their son become enamoured with the numbered and lettered mat, and witnessed him memorize the corresponding colours and letters.

“He played with the mat on a Sunday, and he didn’t see it anymore until Tuesday. [When] we came back home my husband started playing with him … and he said to him [Jose] ‘what colour is letter A?’ just to practice the colour for him,” says Cynthia.

He knows how to speak four languages, can do trigonometry and algebra, and can name up to the 200 digits of Pi.

“And he said ‘blue’, and he didn’t look! My husband was like ‘he learned already the colour from playing on Sunday’ and then he said ‘what is letter B?’ [and Jose responded] ‘green’ without looking at it,” she says. “I still have the receipt when I bought it, and I have the video when he did it. I have everything documented!”

As he’s gotten older, Cynthia has watched her son go from rattling off numbers and colours on a mat like items on a grocery list, to skills that most people twice, or even three, times his age have trouble learning.

He knows how to speak four languages (English, Spanish, French, and Russian), can do trigonometry and algebra, and he can name up to the 200 digits of Pi and the powers of two up to quadrillion numbers.

Cynthia talks with a mixture of admiration and pride about Jose’s remarkable achievements, that it’s hard not to notice the wide grin of parent-pride on her face. And who could blame her? Considering the uncertainty surrounding Jose for the first three years of his life, Cynthia has every reason to be proud of her son and the journey he’s travelled to become a real life version of ‘Young Sheldon’.

A LOVE OF LEARNING

Jose pulls out a calculator, and Cynthia asks me to choose a number between 0 and 53.

“I’m going to calculate two to the power of the number you choose,” Jose says.

“27,” I reply.

Jose stands on the opposite end of the table, as Cynthia turns her iPhone sideways and plugs in the number 27. Jose furrows his brow, twists and turns his face, and starts to carry digits and totals in his mind.

She enters 27 to the power of 2: 134,217,728.

Simultaneously, almost before the calculator had a chance to add up the numbers, Jose responds, “Umm, 134 thousand… No! 134 million, 217 thousand, 728.”

If it wasn’t for the small thousand/million gaffe, Jose might have beaten the calculator.

He credits the mobile phone game 2048 for his inspiration to learn the multiples of two, and estimates it took him a few months to memorize the power of two for every number up to 53.

Jose takes the initiative to learn entirely by himself. Neither Cynthia or her husband push him to become the next Einstein, great mathematician, or force him to study for hours on end after dinner. But Jose has an innate desire to memorize numbers, learn continents, and absorb knowledge from textbooks — because it’s what he loves to do.

Jose takes the initiative to learn entirely by himself. Neither Cynthia or her husband push him to become the next Einstein, great mathematician, or force him to study for hours on end after dinner. But Jose has an innate desire to memorize numbers, learn continents, and absorb knowledge from textbooks — because it’s what he loves to do.

“I always try to give him all other activities, like swimming, he goes to karate, but we go home and when he gets the iPad for one hour a day he watches videos of this. So, that’s his play [time].”

At the age of four, Jose began showing interest in the Russian alphabet. So what did he do? He began to teach himself Russian.

Forget reading Dr. Seuss before bed, or playing Xbox until the wee hours of the morning. Watching videos on YouTube or reading out of textbooks is primarily how Jose learns how to calculate numbers of Pi up to 200, or recite the volume of a sphere in calculus math.

At the age of four, Jose began showing interest in the Russian alphabet. So what did he do? He began to teach himself Russian. Later on, Cynthia found him a Russian teacher, and he has since been attending a weekly Russian school with children of Russian parents.

In addition to languages and numbers, Jose is also interested in topics like anatomy and geography.

Cynthia has been documenting Jose with videos on her personal Facebook account for a few years now, just to prove to friends and family that what she says of her son is true.

She created a Facebook page called ‘Lil Mathematician’ dedicated to highlight Jose’s talents. From working with the cosine law to naming all the countries on the continent of Africa, the page is updated with new content almost every other week highlighting some new achievement Jose has tackled, and has attracted the attention of another young bright mind: Jacob Barnett.

Jacob, a 20-year-old up-and-coming physicist from Indianapolis, has also battled with severe autism to become a well-known genius. When Jacob was two, doctors told his mother that he would never be able to talk, read, or tie his own shoes. However, Jacob defied their prognosis, and was named on the Pacific Standard magazine’s top ‘30 under 30’ list.

Jacob’s mother, Kristine Barnett, pulled Jacob out of special education programs, and instead started to teach her son math and science herself. This sparked Jacob’s passion for letters and numbers, and suddenly at age three nearly identical to Jose’s age at the time, Jacob could speak four languages and answer complicated astrophysics questions.

At eight, Jacob started sitting in on physics classes at Indiana University Purdue University (IUPUI). Fellow students thought Kristine brought young Jacob to class because she didn’t have a babysitter. Only when Jacob started answering questions in class and got an A on the final did IUPUI offer Jacob a spot to enroll.

This inspired Kristine to write a book, The Spark, which documents her story of nurturing a boy genius with autism.

Upon reading the book, Cynthia started to feel comparisons between her life and Kristine’s, and reached out to her to see if Jacob could be a mentor for Jose.

“When Jose was little, I read the book and what she was telling at the beginning [about Jacob], it was describing him [Jose],” says Cynthia while nodding in Jose’s direction. “So, I tried to contact her, and finally I got in touch with her and [now] they even play chess online together and I have videos of them talking.”

Jose and Jacob talk via Skype every Sunday, and Cynthia says it’s great for Jose to learn from someone who’s “like him”.

AUTISM AND INTELLECT

Jose may not be alone. TIME magazine reported on a study that found an interesting link between ‘child prodigies’ and autism. In a study of eight child prodigies, ranging from children gifted in subjects ranging from music to math, TIME found that they all shared common traits — high levels of autism or autism in their close family members.

“The study found a few key characteristics these youngsters had in common. For one, they all had exceptional working memories — the system that holds information active in the mind, keeping it available for further processing,” Maia Szalavits writes in the article.

“Most people can hold seven digits at a time on average; hence, the seven-digit phone number. But prodigies can hold much more, and not only can they remember extraordinarily large numbers, they can also manipulate them and carry out calculations that you or I might have trouble managing with pencil and paper.”

The study went on to report that the prodigies scored high in autistic traits, specifically in their attention to detail. Three of the eight children had a diagnosed autism spectrum disorder themselves, and four of the eight families reported having someone with an autism diagnosis in their first or second degree relatives.

There has even been speculation in recent years — spearheaded by an article published in New Scientist magazine — that Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton had signs of autism.

While Einstein and Newton may have lacked social skills, as well as ample friends, Jose has little trouble interacting with friends his age. Cynthia insists Jose has found his group of friends and niche of people, like Jacob, who have similar interests to him, and believes keeping him at elementary school lets him foster the friendships he already has.

“Really I want to be a science teacher and a person that works on NASA.”

He is currently in grade four, but instead of answering elementary school math, Jose wears a set of headphones and listens to pre-calculus 11 lessons from the South Island Distance Education online school (SIDES).

“Last year [his school] put him in grade seven math, but that wasn’t good enough. They actually at the end had to take him out of the class because he was saying the answers right away and he wasn’t letting other kids to think.”

Cynthia isn’t sure if or when Jose will graduate early. Though he completed pre-calculus 11 in two months and is on pace to finish grade 12 math this year, he still needs to catch up on science and english.

“I cannot bring him to grade 11 english and read Shakespeare, because that’s more abstract. He can read more scientific things.”

Asked what he wants to be when he grows up, Jose immediately replies, “really I want to be a science teacher and a person that works on NASA.”

WIZ KID

Jose asks for my notebook, and begins to scribble math equations and constellations in the remaining few pieces of paper. Over the next six pages, he writes the size and shape of planets and comets down to their exact size.

“So, Hi’iaka is a moon of Haumea, Neiried is a moon of Neptune, Charliko is an asteroid, and then we get to really, really big stuff,” he says, oozing with a confidence that he knows our solar system like the back of his hand.

“Minas at almost 400km (in total diameter), so at almost 400km we’re at Minas, a moon of Saturn. Minas is the smallest spherical moon, Proteus, Neptune’s second smallest moon and the largest non-spherical moon, every moon larger than Proteus is spherical…”

Jose could go on and on about the moons and planets in our solar system, but with the paper in my notebook dwindling, Cynthia suggests Jose saves me a few pieces of paper and shifts his focus back to the Rubik’s Cubes.

He picks up the the Pyraminx, looks up to the clock that reads ‘5:45’ and turns his attention to manipulating the multi-coloured sides of the cube. After a few minutes, he puts the it down, neatly solved, and grabs the second 3-D cube — which he solves in under two minutes.

Jose picks up the final puzzle, and quickly solves half the cube, but before he could get all the sides to their respective solid colours a partially jammed square forces him to ask his mother for help. Cynthia uses her fingernails to pry the Rubik Cube back to it’s workable form and once the piece is back into place, Jose finishes his final puzzle.

The bright red analog clock perched just under the ceiling in the Esquimalt Recreation Centre reads ‘5:54’.