Though it was over three years ago, Jennifer*, a fourth-year UVic student and chronic sufferer of vulvar pain, can still vividly remember receiving her diagnosis. Jennifer was diagnosed with interstitial cystitis, a condition sometimes associated with vulvodynia — an umbrella term for chronic pain affecting the vulvar area without an identifiable cause.

“I remember almost blacking out … [the doctor] handed me a pamphlet and I remember staring at her and thinking,‘What? This is my life now?’” she said. “I started hysterically sobbing, I remember thinking, ‘I can’t live like this.’”

Vulvodynia is thought to affect at least one in six North American women** at some point in their lives — yet it remains largely under-researched, underfunded, and under-publicized.

However, it is very likely that available statistics represent an understatement of the actual number of individuals suffering from this condition. In one study, more than 30 per cent of the women with vulvodynia never sought treatment. Of those who did, over 50 per cent received no diagnosis.

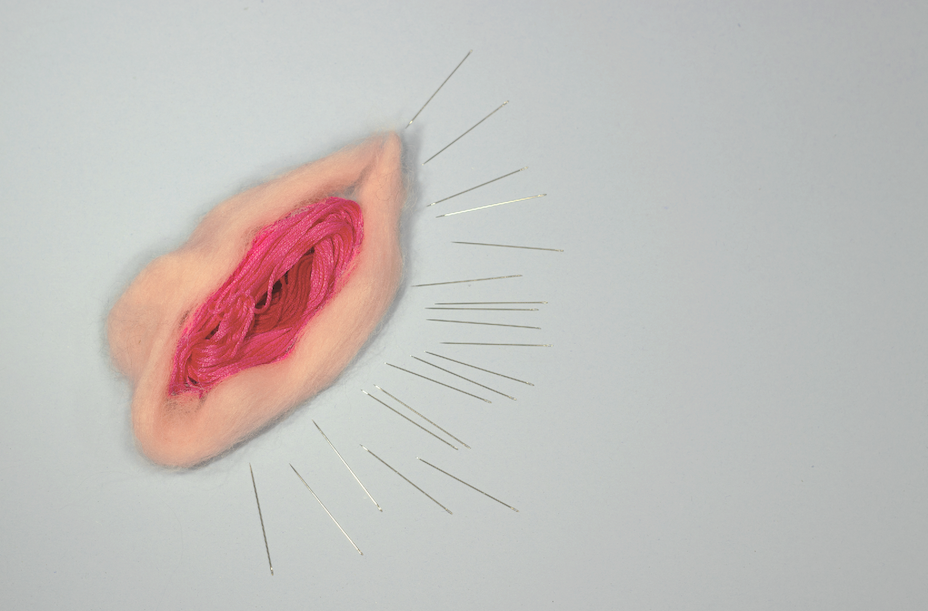

Common symptoms reported by people with vulvodynia include burning, soreness, stinging, rawness, dyspareunia (painful or inability to have intercourse), painful menstruation, and throbbing. Pain may occur constantly or occasionally — particularly when the sensitive area is touched.

Eleanor*, a third-year UVic student and sufferer of poly-cystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), has been in pain since she was 14 years old. Eleanor was a competitive cross-country runner in high school, although running would often exacerbate her symptoms.

“I would have extreme pain that would radiate from my uterus, back area, down my legs, my chest,” said Eleanor. “It would get to the point where I would pass out or vomit.”

Despite the extreme pain, she soldiered on without medical treatment.

“I just kind of brushed it off,” she said.

It wasn’t until Eleanor’s first year at UVic, a full five years after the onset of her symptoms, that she received her diagnosis.

Lack of awareness

Very few healthcare providers correctly diagnose this condition; the average person with a vagina sees seven doctors before finding one who knows how to treat vulvodynia. This is a sobering statistic given that over 50 per cent of cases go undiagnosed.

Noticing this trend, Fawn Whiting, a physiotherapist in Victoria, has recently undergone training in pelvic floor physiotherapy — one of the first and most effective types of treatment for vulvodynia.

“I became much more interested in [pelvic floor physio] because there is a need and I think it is valuable to be able to educate people on what treatments are available,” said Whiting.

“In Victoria, I honestly know of maybe five or six physios that do pelvic floor physio and they all have massive waitlists … there’s a huge need and I think we are starting to educate doctors on the benefits of pelvic floor physio.”

Jennifer’s experiences being misdiagnosed and dismissed prompted her to feel extremely frustrated with the medical system.

“I am so bitter toward doctors because I have always had horrible experiences with them,” she said. “I just feel like there is zero empathy … when it comes to these conditions.”

Eleanor had also encountered similar mistreatment from doctors in her search for a diagnosis.

Doctors told Eleanor it was normal to pass out and throw up from the pain of menstruation. After hearing her symptoms, she said one doctor told her, “Welcome to womanhood.”

Perhaps due to the lack of identifiable causes or society’s general discomfort with female genitalia, vulvodynia is rarely discussed by doctors, medical researchers, the media, or even by the people experiencing the issue. This lack of acknowledgement and awareness has ultimately led to this condition frequently being underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed.

Support options

While this condition is generally disregarded, there are some emerging groups that are listening to the patients with vulvodynia. The most prominent organization of this kind is the U.S.-based National Vulvodynia Association (NVA), a non-profit organization striving to improve the quality of life for those who suffer from vulvodynia.

Susan Kellogg, the Director for Special Medicine at the Centre for Pelvic Medicine is an executive board member for the National Vulvodynia Association.

“One of the great things about the NVA [is that] they really support research and public education,” she said.

Canada is significantly behind the U.S. with regards to vulvodynia research and knowledge — though one local organization, the B.C. Centre for Vulvar Heath (BCCVH), aims to change this.

The BCCVH is one of the only centres in Canada that offers the highly successful Multidisciplinary Vulvodynia Program (MVP). This program utilizes a vast range of treatment methods including medical, behavioural, and surgical treatments, and creates interpatient social support for the people with vulvodynia through group seminars.

Lack of research and funding

The complex issues surrounding vulvodynia and how so many of those suffering from it systematically fall through the cracks have a lot to do with a vicious cycle between the lack of awareness, research, and funding. Due to minimal awareness, there is much less incentive to fund research into vulvodynia. Yet, the lack of awareness of the issue can also be attributed to the scarcity of research funding.

“Part of the enigma of vulvodynia is that it is very difficult to understand. Basic science hasn’t really figured it out, so we’re way far behind,” said Kellogg.

It becomes a vicious cycle: we won’t fund research for vulvodynia if there is no one treatment, yet we won’t find a treatment until we fund research.

“What funds research is major pharmaceutical corporations, and since there is no one treatment for vulvodynia, it’s hard for a single pharmaceutical company to get behind research,” Kellogg said. “I think if [a treatment existed] with a single or maybe two different drugs, a lot of people would get behind it.”

Stigma and gender bias

There is a general consensus in the vulvodynia community that if this condition was affecting men, it would be a different story. Although not only those who identify as women experience vulvodynia, it is a condition that faces a lack of resources and attention due to gendered stigma. Evidence of this can be found by looking at the way erectile dysfunction is handled compared to vulvodynia.

Erectile dysfunction, a condition that affects a man’s ability to become erect enough to have sexual intercourse, has no pain associated with it — yet there is an abundance of research, treatment, and awareness. Vulvodynia not only affects a patient’s ability to experience sexual pleasure, it also causes intense pain. However, vulvodynia receives far less attention and funding.

The U.S. National Vulvodynia Association reported that studies indicate a gender bias in how patients with pain receive medical treatment.

Canada does not publicly release figures on how much of the budget is spent on these specific conditions. Research done by the U.S.-based National Health Institute (NHI) in 2010 showcases the disparities between funding for chronic pain conditions, revealing that conditions that predominantly affect women are dramatically underfunded compared to other chronic conditions. Vuvlodynia received less money than any other condition cited, less than one per cent of funds put toward researching depression.

The future

So, what does the future hold for vulvodynia? Although the current state of affairs for vulvodynia may seem bleak, health care providers urge the public not to lose hope.

Kellogg points to Ipsum, a France-based pharmaceutical company which is currently funding a vulvodynia trial.

“They are, to my knowledge, the only drug company that has stepped forward and funded a multi-centred trial,” she said. “It’s really great, I am very happy with them.”

While a one-stop cure for vulvodynia may still be a long way off, Kellogg expressed her optimism at the future of treatment and wider awareness.

“There is most definitely hope,” said Kellogg. “There is growing public awareness of this condition and its subcategories. Places like the National Vulvodynia Association and the National Institution of Health … are really starting to [allocate] funds for it as well because they do realize how big the problem is. So it’s just starting; it’s in its infancy.”

Whiting shares Kellogg’s vision for improved resources for medical professionals to learn about and treat vulvodynia.

“It’s slowly, slowly changing — more physios [are] educating themselves and then educating doctors in the area,” Whiting said. “In the future, we will see more people and physios available to treat this condition … hopefully [Canada] will become ahead of the game or at least on par with it in terms of providing care and general awareness.”

As for people with vulvodynia, in the meantime, many do as Eleanor does.

“I just keep running,” she said.

*Names of sources have been changed to protect their identities.

** Not all those who suffer from vulvodynia are women. Gendered language is used to reflect the specified demographic results of statistics and studies cited in this piece.