Navigating the spectrum of the transgender and non-binary experience

March 31 marked the international Transgender Day of Visibility (TDOV), a day meant to celebrate and empower the trans community. This year’s theme was #TransResistance: a reaction to global transphobia in the current political world.

The passing of TDOV made me question, as a cisgender woman, just how much I understood about our own transgender and non-binary community on campus. In truth, it wasn’t until I heard a guest lecture last semester by Dr. Aaron Devor, research chair of transgender studies at UVic, that I even learned there was a difference between the terms sex and gender.

Since then, I started to wonder whether or not we still have work to do in order to make campus accessible and safe for all our students. With the largest transgender archives in the world just within our library, how come cisgender people like me still have an issue understanding what being transgender or non-binary means?

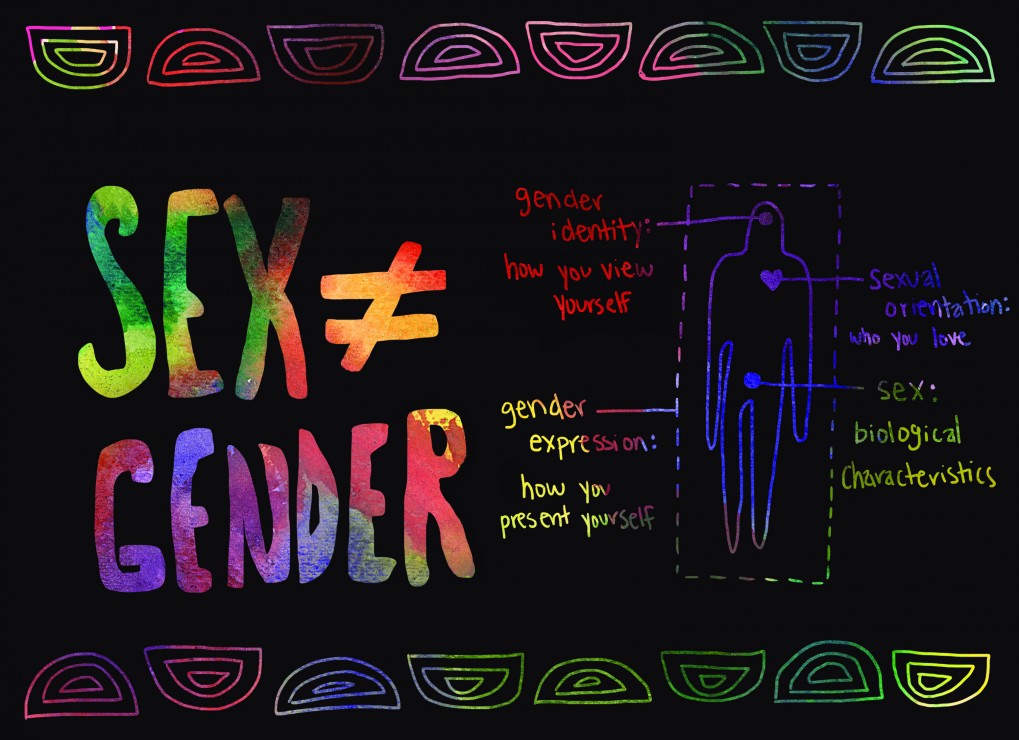

According to Devor the majority of people use the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ interchangeably. “In most people’s lives, it’s really an inconsequential difference. But for transgender people, it’s an important difference.” As Devor says, “sex is about your body and gender is about how you feel and act in the world.”

Daphne Shaed, a UVic student who is a trans woman, says she constantly has to explain or teach people on campus about gender. “People always expect marginalized persons to teach them about their marginality,” she says. “And especially since I’m a very outspoken individual on the radio where my intro is ‘I’m a woman with a penis.’”

Shaed hosts Breaking Binary at CFUV where she talks with her radio co-host about issues surrounding bodies and gender. “Sex doesn’t make your gender,” Shaed says. “You can be a woman with a penis, you can be a man with a vagina. You can be genderqueer with whatever bits you want.”

SEX AND GENDER

According to Devor, sex is best understood as a description of physical characteristics determined at birth: male, female, or intersex. “Rarely is there any more detail to it than that, and that sets the stage for your entire life,” Devor says. If the sex is unclear, then the baby is intersex and the parents usually choose a gender.

However, Devor explains that for trans or gender non-binary people, their identity does not stem primarily from their physical self. “It stems from how they feel that they best fit in the world.”

“Gender is what we deal with in everyday life,” Devor explains. “The way a person acts, talks, dresses, what their interests are, how they move, et cetera. These things are all components of gender.”

The terms most often used to describe gender include man, woman, trans, or gender non-binary, among others. “Binary refers to the concept that everyone is either a man or a woman, and some people say, ‘Nope, that doesn’t work for me’ and they call themselves gender non-binary because they don’t fit into one of those two categories,” says Devor.

Val Ackroyd, a second-year Visual Arts student, says they identify as non-binary. “I don’t generally feel like I need to explain where exactly I fit on a spectrum of identities, [because] gender is a part of a spectrum and it’s not necessarily black and white.”

“Gender is weird,” says fourth-year writing student Serena Bhandar, who is a trans woman. “We view it as a straight line from feminine to masculine but we also view transness as a straight line from trans-woman to trans-man,” she says. “It’s definitely not as clear as science would put it.”

GENDER IDENTITY AND GENDER EXPRESSION

The important thing to remember is that a trans or non-binary person expresses their gender identity through the way they dress, act, talk, and so on, and that their gender identity is not determined by their body. Devor explains that there are two assumed binary gender roles: femininity and masculinity, though for many trans and non-binary people, gender expression is less cut and dry.

“To a large number of people, masculine/male/man are all synonyms,” says Shaed. “And same with female/woman/feminine. I think a lot of people read them all as the same thing.”

But, since female/male refers to sex, woman/man to gender, and feminine/masculine to expression, gender and gender expression are often more fluid for many people.

Shaed says she had a more “ultra-feminine” expression while at Camosun College. “It felt more inclusive in some ways. When I was at Camosun, I would be very what I would call high-fem, super feminine.”

When she first transferred to UVic, Shaed found it to be more intimidating and less inclusive, so she altered her gender expression even though her identity is still ultra-feminine. “There was a larger campus to navigate . . . So I kind of dressed it down a little bit. Plus I work on campus. I go to class and then I run to work in between all that, so I was just doing a lot more, and those ultra-feminine clothes didn’t lend themselves to walking across campus.” Now she dresses that way out of convenience.

Being non-binary, Ackroyd says they tend to dress however they want. “I guess I don’t have much of a basis for presenting myself. I know that a lot of non-binary people prefer to look really androgynous or as androgynous as they can be.”

In some cases, transgender or non-binary people resort to using different resources to fully express their gender identity. On campus, UVic Pride offers a range of assistance to students and community members, such as its Gender Affirming Resource Program, which includes a variety of products.

“We just help people locate gender-affirming resources,” says Lux West, UVic Pride office coordinator. “So binders, breast forms, packers, and larger sized women’s shoes because they can be hard to find in stores. We try to offer as broad a range as possible. We also have syringes for testosterone administration. Lots of stuff.” For anyone facing a barrier to accessing resources, Pride offers as much assistance (including funding assistance) as possible. As of yet, they are the only organization on campus that offers this kind of support.

Pride offers this wide array of resources in order to better meet each individual’s needs, and while some people take hormones to affect their gender expression, only a minority of trans people undergo full genital reassignment surgery.

As Devor says, “trans and non-binary people want to be recognized on the basis of their gender identity, not on the basis of their bodies. If they bring their bodies in line with their gender identity, then that’s great, but they shouldn’t have to.”

PRONOUNS AND AFFIRMING GENDER

One thing that Devor cautions people to remember is that not everyone feels safe to express their gender identity, and that one shouldn’t assume someone’s identity based on the degree to which they choose to express it. “You need to be cautious about making assumptions based on what somebody looks like, about how they actually identify themselves,” he says. If a transgender/non-binary person’s gender expression is misinterpreted by a cisgendered person, it can work against their gender identity.

“Say you have a female body but your identity is male,” explains Devor. “And your gender identity is as a man and you try to show yourself as a man, but people see that you have breasts. What people are attributing to you is being female because they see those breasts . . . and so your gender identity does not get reinforced by the attributions that people make.”

And some transgender/non-binary people may have a consistent identity but only sometimes show it. “There’s a lot of people who are for instance male bodied,” Devor says, “and sometimes express their more female or feminine side, and sometimes don’t.”

An important aspect of gender affirmation for many trans and non-binary people is their pronouns. Ackroyd finds that it’s hard to approach people about using their pronouns and stating their identity. “There’s so much backlash against not just trans people who use she/her and he/him pronouns, but also against non-binary and other identities.

“I think that because people don’t have a basis of understanding about those kind of things . . . I have to give this brief gender 101 [lesson] to anyone I talk to explaining how I do that. It just really goes to show that not that many people have that background of knowledge.”

Ackroyd has told others to use ‘they/them’ pronouns when referring to them, but finds people often forget.

“My partner is also trans and non-binary, so I would explain their identity first because I would prefer if their pronouns were respected before my own,” Ackroyd says. “Usually that’s when things get kind of complicated, because people are still misgendering them and I’m correcting [those people], and they’re like ‘Oh, I make mistakes’ and all that dismissive language comes in.”

“Pronouns are very important to all of us because pronouns again reinforce or undermine the validity of our gender identities,” Devor says. “So you want people to address you using pronouns that are consistent with how you see yourself.”

Devor reminds us that in the past, it was grammatically correct to use ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ for the singular, and ‘you’ for the plural. “I believe that it’s not going to take people very long to get used to using ‘they’ in singular and plural, just like we’ve gotten used to using ‘you’ in the singular and the plural.”

Bhandar tells people to keep an open mind and not shut down someone’s pronoun use with the argument that it’s not grammatically correct. “Grammar is fluid,” she says. “Language is fluid. And society is fluid. And it can change.”

COMING OUT OR OUTING

One thing Bhandar seriously warns against is outing people by accident. “Always check for consent when you’re talking about someone who’s trans,” she says, “because the potential for violence against them and potential risks outweigh the inconvenience of checking in with them.”

This can be the case when students have family members visiting, are at work, or simply just on campus. “Unless a person is openly trans and has said, ‘Please use these pronouns when you’re talking about me with somebody else,’ or this name, then don’t out someone as trans to a random person.”

For Ackroyd, they usually come out once they’ve grown close enough to someone to feel comfortable, but they’re definitely afraid to tell people for fear of having to justify it. In their case, not every experience coming out to their peers has been pleasant.

One time Akroyd told a student in class that they were trans. “The next day, and from that point on, they didn’t sit anywhere near me. They actually went to the other side of the lecture hall.

“And part of me is trying to justify that like, ‘Oh, maybe they just prefer sitting over there’ or something, but internally I imagine it’s just because it’s difficult to have a conversation with me.”

Shaed also has anxiety on the first day of classes, and often has to ask herself what the demographic of the class is like and if she’ll be welcomed by her fellow students. “All these kinds of social nuances of social anxiety are amplified for queer and trans and two-spirit and other kinds of marginalized persons.”

Ackroyd encourages people who have questions about identities and gender to ask a friend that is of that identity, or to check online resources. “Just going up to a stranger that you know is trans could a) be really traumatizing for that person, and b) it might not be a safe space for them to come out to you or be outed,” says Ackroyd.

With so much information available online or through the Pride Centre, it doesn’t make sense to approach just anyone. “Unless they are okay with having this conversation with you, consider that it could be really emotionally overwhelming or dangerous to talk to someone in a not safe space,” Ackroyd says.

GENDERLESS BATHROOMS

For Shaed, one of the biggest issues on campus is the lack of genderless bathrooms. The SUB is the only building on campus with an explicitly gender-neutral bathroom, which poses a challenge for some. Some travel across campus just to access washrooms where they feel safe.

Shaed says that she’ll often use the washrooms on upper floors where people are less likely to go. “I’ll go up to the fourth floor bathrooms where there’s like nobody, or where they’re less frequented because there’s less offices and less faculty there.”

The bathroom issue is something Ackroyd feels passionate about, as well. “I attend class in the Visual Arts section which is the complete opposite end of the school than the Student Union Building which really has the only unisex bathroom, aside from handicapped bathrooms, but I don’t feel comfortable taking space away from disabled people.”

Shaed has been told that there are seventy-five non-gendered bathrooms on campus. However, the majority of those are single-stall washrooms designed to provide access to people with disabilities. “What needs to happen is UVic needs to take at least one set of multi-stall bathrooms in each building and just modify them to be genderless. Not even gender neutral – stop bringing gender into the freaking bathroom.”

IS UVIC A SAFE SPACE?

According to Shaed, “UVic pretends that it’s welcoming.”

Shaed says people who are not trans or queer see the image UVic presents and believe that campus is a safe place. They see the rainbow crosswalk and the Transgender Studies chair and think there isn’t any work left to be done. “It’s actually made it harder for grassroots activists on campus like myself,” she says.

According to Shaed, campus is no different than anywhere else in the city. “Be alert. Be aware. Expect harm.”

Lux West says it’s a little more complicated. “I think that there are spaces at UVic that are definitely safer than other places in the city for trans people.” However, they acknowledge that more recently there has been “a pretty big insurgence of specific violence towards trans women on campus.”

In incidents last summer and fall, for example, numerous transphobic notes and messages targeting and naming Shaed were left at the Third Space, where she currently works as a volunteer coordinator. Other messages spoke directly against trans-feminine people, and one went as far to say, “If you see a man in the bathroom call 911.”

“They were referring to trans women,” Shaed says.

However, West says that through this process, Pride was able to identify where they were and weren’t getting support. “It’s interesting because I can now say that there are definitely places, mostly in the SUB, that I would consider to be very safe and a good place for trans people to be,” West says. “There are places and there are aspects that UVic is a great place to be for trans people, but there’s lots of aspects that make it not good at all.”

For Serena Bhandar, she’s thankful not to have experienced violence on campus personally, but is unsure of what she would do if it did occur. “I’m fortunate not to have had anything hugely violent or physically violent happen to me.

“But I don’t know what would happen if that would happen,” Bhandar says. “I don’t know what supports exist.”

As a cisgendered woman, I will never know or experience these issues myself. I can access a number of bathrooms whenever I want, I never have to correct the way people refer to me, and my anxieties around starting classes stem from how long the essays will be, and not from the threat of prejudice or violence.

As an ally, I’m still learning. I have a long way to go, and so does UVic. The way to fight our ignorance is through education, by asking questions and seeking answers, so that we can make our campus safe for all students. But we can’t sit back and expect the hard work to be done for us.

“There’s this idea in Western cultures about linear progression where we assume that with time things will always get better,” Bhandar says. “Society changes. Sometimes it changes in ways that we want and sometimes it changes in ways that we don’t want, and we can never assume that things are always just going to get better.

“We have to be vigilant and active.”