On Jan. 25, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock moved ahead thirty seconds to two minutes to midnight: the closest humanity has been to extinction, by this measure, since 1953. The change is due to the worsening of the two main threats to human survival — nuclear war and climate change.

While the world shudders listening to Donald Trump’s bombastic provocations towards an increasingly agitated North Korea, this isn’t the first time humanity has grappled with nuclear obliteration.

In 1983, Russian radar officer Stanislav Petrov was on watch one evening when his system displayed six inbound U.S. warheads. Doubting his readings, he refused to give the retaliatory launch order. It turns out Russian satellites had incorrectly identified sunlight reflecting off the clouds as missile trails. Petrov correctly reported a system failure and saved humanity from a nuclear holocaust.

It seems as though we’ve learned from our mistakes, especially when Justin Trudeau tells the Globe and Mail that “we need to create a nuclear-free world for our children and grandchildren.”

“We’re focused on significant, concrete measures moving forward that will actually include countries that have nuclear weapons,” Trudeau said in the same Globe and Mail interview.

But on July 7, 2017, when 122 countries endorsed the U.N. Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, Trudeau and Canada refused to participate in any way. Canada did not sign or even vote on the treaty. To date, 56 countries have signed it and four have ratified it in their national parliaments. Once 50 ratify, the treaty will come into force.

No nuclear-weapon-holding states signed the treaty, nor did any country in the U.S.-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization. In fact, every signatory country was from the Global South, except for Austria, Ireland, Liechtenstein, New Zealand, and the Vatican.

For Trudeau and the Canadian government, “concrete measures” could mean erecting defences against a nuclear attack. The Canadian parliament has been debating the installation of a U.S. nuclear missile defence system in Canada despite skeptical testimony on the project to the Canadian Senate in 2014.

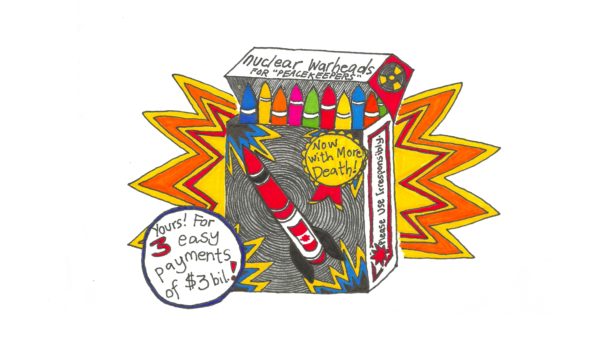

Graphics by Nat Inez, Graphics Contributor

The system, called ballistic missile defence (BMD), has been under debate in Canada for several years. A 2014 Senate report stated, “the committee is unanimous in recommending that the Government of Canada enter into an agreement with the United States to participate as a partner in ballistic missile defence.”

This would involve installing radar stations and ground-based anti-ballistic missiles, which cost $75 million each, throughout the country. They are designed to intercept and destroy incoming nuclear missiles by detonating conventional explosives in the vicinity.

The Canadian Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence noted Iran and North Korea as the main nuclear threats in the 2014 report, though Iran has no nuclear missiles.

These purported threats steal attention from the possibility that BMD may not be able to shoot down incoming missiles.

Dr. Dean Wilkening, a physicist interviewed by the senate, said the missiles in development had “not performed well on the test range.”

Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Robert Gard Jr. testified that the system had an inability to discriminate an incoming warhead from debris created by a partial interception, noting that “radar and infrared are simply incapable” of a high level of discrimination. Despite that, the senate voted unanimously to recommend BMD to parliament.

In September 2016, the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence did not rule out BMD. Their report stated that the U.S. had spent $45 billion to develop an existing arsenal of 30 interceptors, though the U.S. Government Accountability Office reported in 2014 that $98 billion had been spent on BMD since 2002. So the cost of the program to Canada would be difficult to predict.

Pursuing an unproven plan to defend against a nuclear attack is preposterous. The safest thing to do is to destroy nuclear weapons before they destroy us.

That is why the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) advocates for complete worldwide nuclear disarmament. For its efforts, ICAN received the Nobel Peace Prize on Dec. 10, 2017. The Nobel committee’s website states that “the organization is receiving the award for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons.”

Staff and students from the University of Victoria contributed to ICAN’s campaign on Sept. 20, 2017 when the Vancouver Island Peace and Disarmament Network (VIPDN) collected petition signatures in front of the McPherson Library. VIPDN chair Dr. David Monk, also a sessional instructor in the Department of Education at UVic, organized the event.

“Since January, we’ve been putting pressure on the Canadian government to sign the treaty,” Monk said. “[But] Trudeau isn’t wanting to rock the boat with the U.S.”

In siding with Canada’s nuclear armed allies, Trudeau put political advantage ahead of ensuring human survival in an increasingly volatile world.

Murray Rankin, Member of Parliament for Victoria, delivered the VIPDN petitions to the House of Commons on Oct. 20. “These constituents call upon parliament to take a position independent of NATO and the United States and support the treaty to prohibit the development, production, transfer, stationing, and use of nuclear weapons,” he told his fellow MPs.

Still, prominent figures in Canada support BMD. In August 2017, Senator Romeo Dallaire, deputy chair of the senate security committee told the Toronto Star, “Canada should join the ballistic missile defence program.”

Mary-Wynne Ashford is a VIPDN member and a lifelong nuclear activist. Ashford authored Enough Blood Shed: 101 Solutions to Violence, Terror and War and was invited to speak at a nuclear disarmament conference in Moscow in 1987. (The conference was also attended by Justin Trudeau’s father, former Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau.)

She began her nuclear activism in 1984 after she learned about Petrov narrowly averting a nuclear holocaust the year before. And, in an interview with the Martlet, she called BMD “a useless waste of money,” due to the extreme likelihood that it will fail to stop a nuclear attack.

Trying to intercept an incoming missile, according to Ashford, is “like shooting a bullet with a bullet.”

Canada, the U.S., and NATO are not helping to alleviate nuclear tensions, and the notion that North America can defend itself from a nuclear attack is naive and dangerous.

In their most recent statement, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists wrote that “humankind has invented the implements of apocalypse so can it invent the methods of controlling and eventually eliminating them.”

To that end, VIPDN and the UVic Centre for Global Studies are sponsoring a forum called “The Growing Danger of Nuclear War and What We Can Do About It,” featuring Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Ira Helfand.

This free talk will be held in the Human and Social Development Building, room A240, on Feb. 9 from 7–9 p.m.