The Science of Discworld IV: Judgement Day is an amusing and unusual beast. Like the rest of author Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, it is set mostly in a satirical fantasy world, a flat disc resting on the backs of four giant elephants that stand on a colossal sea turtle swimming through the depths of space. In case you are unfamiliar, know that each book generally resembles the pampered lovechild of The Lord of the Rings and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, having inherited the sword-and-sorcery tropes of the former and the dark-yet-warm absurdist humour of the latter.

What sets the Science of Discworld tetralogy apart from the rest of the Discworld series is its unique composition: odd-numbered chapters telling segments of a fantasy/comedy story are followed by even-numbered chapters that consist of scientific and philosophical commentary. Given the strong focus on science and philosophy already present in all of Pratchett’s work, these particular non-fiction discourses make the perfect complement for his storytelling.

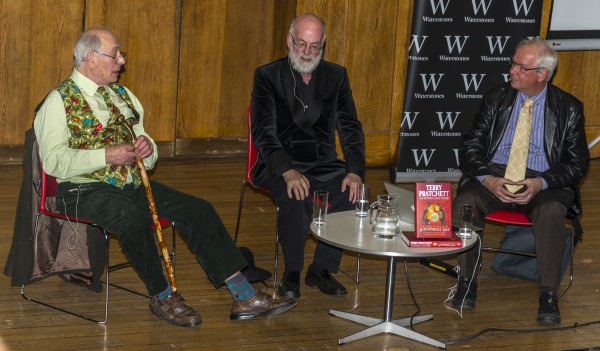

Pratchett enlisted two experts to collaborate on the science chapters. They are Professor Ian Stewart, an Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick, and Dr. Jack Cohen, an internationally renowned reproductive biologist. Both share Pratchett’s passion for promoting critical thinking and knowledge, and both have the writing and educating chops to fully realize that passion, delivering a broad overview of the history of scientific inquiry and its current state, as well as some clever insights of their own. Prominent among these insights are some fascinating—if not actually groundbreaking—arguments for a particular delineation of the domains of religion and science, supported by a distinction drawn between “human-centred” and “universe-centred” worldviews. The distinctive voices of all three authors are strong throughout the science chapters, as is their sheer enthusiasm for the study of nature and humanity.

Apart from some slightly denser portions near the middle, related to particle physics, the science chapters also tend to be extremely accessible to laypeople, while still maintaining an academic spirit. The most important sections—those having to do with the essence of the scientific worldview—are by far the most elegant and easy to understand, and the most strongly linked into the fictional chapters. Of course, to some extent, every chapter deals with such concepts; each one contributes weight to the central thesis.

In case you are expecting the equivalent of a full Discworld novel, be warned that the science chapters take up a greater portion of the book’s length, while all the fiction chapters together add up to something more along the lines of a novella. While not as grand of an adventure as usual, it still has the requisite features of a good Discworld yarn: blustering wizards, eldritch mishaps on a cosmic scale, and belligerent deities. Pratchett has always had his sights set firmly on a nerdy, bookish readership, and The Science of Discworld IV is no exception, sporting an intrepid librarian from Roundworld (our Earth) as a new main character. This is an agreeable bit of blatant pandering for anyone likely to pick up the book in the first place, though the epilogue carries it a little too far, into sappy territory. All told, the book is wonderfully imaginative and edifying, though it is perhaps more effective for devotees of real-world intrigue than for escapists.