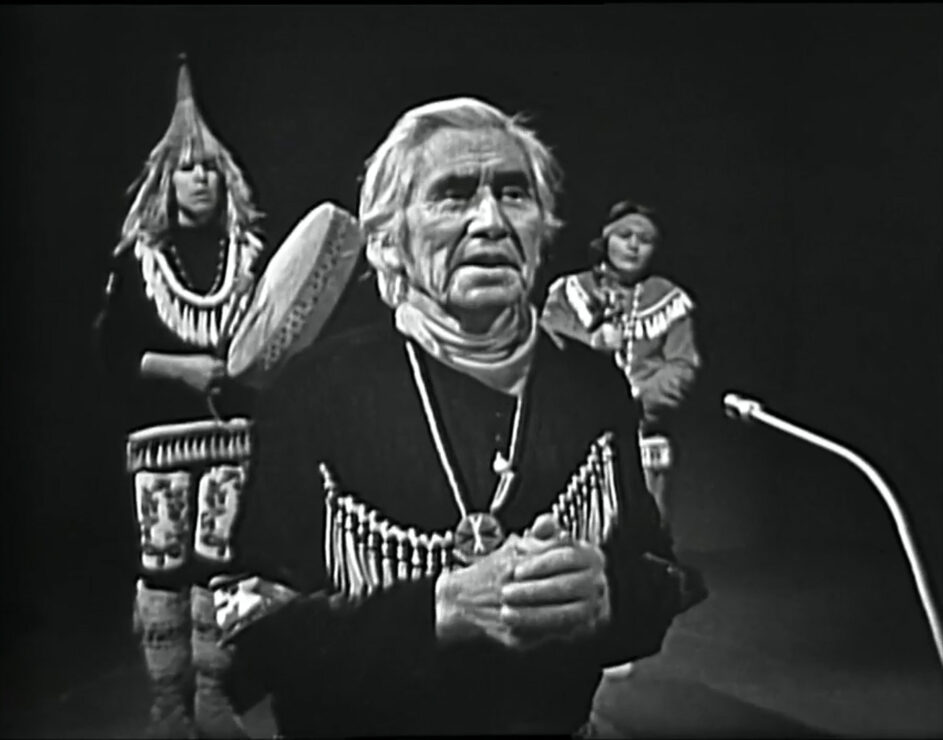

In the 55 years since this iconic speech, what has changed?

55 years ago Chief Dan George gave the iconic ‘Lament for Confederation’ speech during Canada’s centennial. For Indigenous Canadians, this speech carries a great level of significance due to it being one of the first of its kind. Since ‘The Lament for Confederation’ reached a broad audience, Chief Dan George was one of the first Indigenous peoples to speak to mainstream society about the Indigenous perspective on confederation. However, the importance of this speech has been buried in the sediment that is Canadian politics over the last half of a century. But the relevancy of this speech has never faltered.

Although progress has been made in the last 55 years, it is important to note that there is still a long road ahead to achieve a sense of justice and equity in upholding Aboriginal title. There is still more to improve in order to become the nation Chief Dan George envisioned by 2067. While the sense of progress is important to celebrate, it is also equally as important to know what lies ahead.

As we navigate into the 155th year of confederation for Canada, we must be aware of what long-standing issues still persist to this day.

Indigenous rights to food sovereignty

Chief Dan George said it best himself in his speech: “Those waters said ‘come and eat of my abundance.’” This philosophy included all traditional foods that ensured Indigenous peoples had food sovereignty and food security to sustain their nations.

But in 2021, the understanding of food sovereignty is a largely contested issue within the settler colonial state. For example, the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia faced violence when they tried to open an Indigenous-owned fishery. In 2020, the Sipekne’katik First Nation found themselves subjected to lobster disputes that lead to physical assault, arson of property, and theft. These contentions hindered their Section 35 and treaty rights. This also stalled their right to self-governance and economic independence as Mi’kmaq fishers.

Risk of empty oceans

In the Netflix documentary Seaspiracy, director Ali Tabrizi discusses the possible effects of poor ocean resource management: an empty ocean. The poor management has been especially felt by coastal Indigenous communities as these communities have depended on the ocean for their survival and wellbeing since time immemorial.

Chief Dan George saw this issue coming too. In the ‘Lament for Confederation’, he explains, “But in the long hundred years since the white man came, I have seen [my] freedom disappear just like the salmon as they go mysteriously out to sea.”

So how long do we have to fix this? While that is a great question, it can defer the sense of urgency for many who do not and have not directly depended on the ocean’s resources. The realistic answer is that we should be fixing it now. However, according to Seaspiracy’s website which uses information from a 2020 report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “93.8% of fish stocks are either biologically unsustainable or at their maximum level of exploitation.” The documentary predicts that we can expect empty oceans by 2048.

High School Regalia

While the first portion of this article paints a picture of the grim and harmful reality that colonialism has brought to Indigenous Nations, it is important to note that things have improved over the last 50 years.

More recently, our children have been comfortable enough to wear their regalia and showcase their authentic cultural selves. But for some, it is still a challenge to do so without being mocked. In Kitimat, British Columbia, Gregory Grant wore his traditional Haisla regalia to his school for picture day. However, the Mount Elizabeth Middle Secondary student was asked, ‘What’s up with the costume today?’ in front of his peers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.

Chief Dan George would be proud of the student. However, I am sure he would also be disappointed that our students still face this kind of ignorance and racism in their own territories. This is an example of “dominating space.” In which, Chief Dan George says, “Let me again, as in the days of old, dominate my environment” — much like the Haisla student did here in 2021.

Indigenous peoples in government

As I have mentioned, a lot of changes have come over the last 50 years. From the B.C. government implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to the new federal National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, there have been monumental changes. By and large, a lot of this change has to do with Indigenous peoples actively participating in our democracy. Not only are Indigenous peoples voting, they are also being elected to office. For example, Jody Wilson-Raybould became the first Indigenous person to serve as the Minister of Justice in 2015. On a provincial level, MLA Melanie Mark became the first First Nations woman to serve in British Columbia’s cabinet. Two provinces over, Wab Kinew became the first Indigenous person to lead the official opposition in Manitoba. It is safe to say, change is no longer on the horizon. Change is here!

Chief Dan George aspired to have this happen for future generations. In the ‘Lament for Confederation’, he says, “I shall see our young braves and our chiefs sitting in the house of law and government, ruling and being ruled by the knowledge and freedoms of our great land.”

Currently, only two out of the 13 premiers are Indigenous, and the prime minister is not and has never been an Indigenous person. However, the Governor General of Canada Mary Simon is. Simon holds the highest symbolic role in Canadian society. Due to the tumultuous relationship that Indigenous peoples had with the crown, some may disagree with her role representing the Sovereign. Likewise, others are upholding her appointment as an example of reconciliation.

In 2021, it is great to see the changes are coming through all aspects of society. This will help to ensure the next 45 years of Canada are both equitable and just for Indigenous peoples.