Hundreds showed up to support intersectional feminism with a focus on Indigenous women’s rights

Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

Sunshine broke through the rain clouds on Saturday, Jan. 19, as a crowd gathered on the Legislative precinct for the third annual Women’s March. The procession was led by Indigenous women, transgender women, and other members of the LGBTQ2+ community.

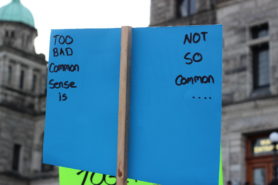

Although pink hats with ears, called ‘pussy hats’, became a symbol of feminist unity following the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, these could only occasionally be seen bobbing among the crowd this year. Women’s March Victoria released an official statement calling pussy hats “transphobic” because “Not every woman has a vagina, and not every person who has a vagina is a woman. In addition, not every pussy is pink.”

Based on a suggestion made by the Native Women’s Association of Canada, many people wore red scarves in recognition of the disproportionate violence experienced by Indigenous women and girls in Canada, who are three times as likely as other Canadian women to experience violence.

“Today we march for our stolen sisters, our hard-working mothers, our born and unborn kids and grandkids.”

Women’s March Victoria media spokesperson and University of Victoria student Astra Lund-Phillips stated that the march organizers “especially wanted to focus on the experiences of Indigenous women, girls, and non-binary folks this year, as we believe feminism is only true feminism if it’s intersectional.”

The demonstration began with speeches by Indigenous women Tiffany Joseph and Rachelle Kooy, who also led a Women’s Warriors song.

Joseph, who grew up on a reserve in North Vancouver, spoke with a red paint handprint across her face.

Tiffany Joseph speaking in front of the legislature. Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

“This paint represents the blood I shed every month,” she said.

Joseph’s speech emphasized the cultural role that Indigenous women have in caring for the land and for others, and called upon law enforcement to respect and believe those who come forward.

She voiced a heartfelt plea that all Canadians “see [Indigenous peoples] for the leaders who have been invisible to you for so long.”

Kat Sark, the Women’s March Victoria chapter leader, reminded participants of what the march was for.

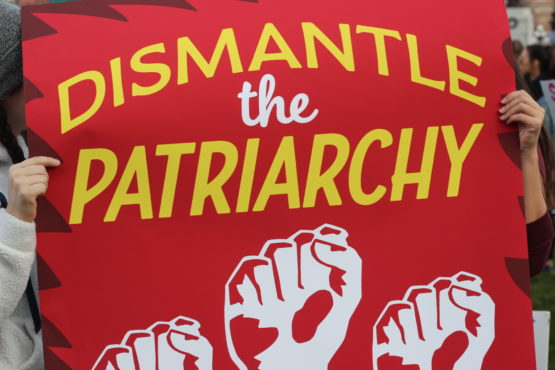

“Today we march for our stolen sisters, our hard-working mothers, our born and unborn kids and grandkids…We march because we can no longer be bystanders, because we want to build communities of care in which women matter, human rights matter, LGBTQ rights matter, Indigenous laws matter, the environment matters, and justice matters,” Sark said.

For some, the focus on Indigenous women was especially meaningful.

“As a woman, as a settler, it’s my duty to support in any way I can and raise awareness that we can’t keep ignoring this situation [regarding the murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls]. I think it speaks to patriarchy, I think it speaks to so many pieces that bind us as women, and so to begin to untangle us we have to come and show up at these events and listen to other people and their stories,” said Lindsay Lichty, a march participant.

Rachelle Kooy leading the Women’s Warrior song at the legislature. Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

Rachelle Kooy, one of the speakers, is fed up with injustice.

“It’s 2019 and we still have to take to the streets for women’s rights,” said Kooy. “One of my own relatives, who is a student at UVic, just bought a high visibility jacket for running because she just knows as an Indigenous woman she is further targeted.”

For Kooy, equality is essential to society.

“We all have something to offer, every single one of us. We have unique perspectives, we have unique wisdoms, and if we’re not having people feel safe in their communities where they live, or where they’re studying or working, then how are they going to thrive and be contributing?”

Elizabeth May, leader of the Green Party of Canada — and the only female leader of an established Canadian federal party — participated as a proud feminist, overjoyed to witness the inclusivity visible at the march.

Elizabeth May and her assistant Leah Hayward. Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

“In my sixties, I’m part of that earlier feminist wave and for a while … I was feeling that people wanted to say ‘oh, I’m not a feminist. Oh dear, that’s too radical to be a feminist,’” she said. “It’s wonderful to see women of all ages organizing and particularly the focus on marginalized communities, on Indigenous women, on women in poverty. It makes me very proud to march in solidarity.”

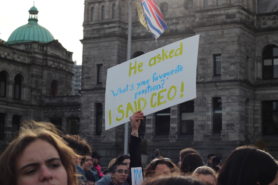

A group of students from Pearson College, a United World College School that welcomes pre-university students from all over the globe, grinned and whooped as they posed with their signs.

Mikella Schuettler, thrilled to have her “On Wednesdays we Smash the Patriarchy” sign understood as a Mean Girls reference, said that Pearson’s Rights and Justice group organized a bus for students who wanted to attend the march.

For some parents, the march was an opportunity to educate their children.

“Equality is good, but “really, we want justice.”

Peter Rosenbluth participated in the march for the sake of his young son and daughter.

“I’m here ‘cause I think it’s helpful for them to see so many people who feel the same way about fairness, and fairness is something that kids understand, or should be understanding intuitively,” Rosenbluth said.

Steven Price said that he and his son were marching to support his wife, and his daughter who rode perched atop his shoulders.

Steven Price with family. Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

For some older participants in the march, demanding equality is nothing new, and they are fierce about it.

Marina Smith and Sheila Moss, Sisters of Saint Ann, have been involved in feminist movements for a long time. According to Smith, equality is good, but “really, we want justice.”

The march ended at Centennial Square, where local grassroots movements had tables set up to explain the work they do in the community.

Sage Lacerte was at the march representing the Moosehide Campaign, a movement that seeks to engage Indigenous and non-Indigenous men and boys in ending violence towards women. She said that as a young person of colour, she realized that violence affects not only her own life, but the lives of people nationwide.

Sage Lacerte of the Moosehide Campaign.

“I’m doing this work [with the campaign] to say that it’s not okay, and violence is not love, and that we need to be more mindful and respectful of the people around us.

Lacerte’s nephew, Jackson Macrae, also commented on the march.

“I’m happy that everyone’s here to respect that Indigenous women and children can just not be treated as fairly as others. I think it’s important that we stand up to that and make sure it’s right,” said Macrae.

Despite the focus on Indigenous women, the Women’s March Victoria chapter has been criticized by some on social media for not being inclusive enough. Unlike previous years, there were fewer speeches this year, and some took offense at the resulting lack of Indigenous speakers.

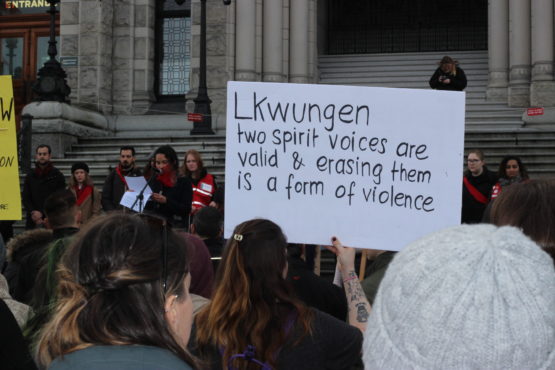

In a post on the Women’s March Victoria Facebook page, Bitty Qlamgardner, a local Lekwungen Two-spirit community member, accused the march organizers of “violence” and of silencing Indigenous voices by not allowing Ma’amtagila Matriarch, Tsastilqualus Ambers Umbas, to make a speech.

Statements have been issued on Facebook by both Sark and the new Victoria chapter leader Shay Lynn Sampson, apologizing for any mistakes or miscommunications on their part, saying that speeches were cut as a result of feedback from last year. Sark said that the new format was supposed to allow for more face-to-face conversations with grassroots organizers.

In the end, however, Ma’amtagila Matriarch Tsastilqualus Ambers Umbas did make a speech at Centennial Square.

And, all the same, the Victoria Women’s March saw hundreds turn out in what ended up being a rare sunny day in B.C.’s capital city.

This article was updated on Jan. 28 at 4:57 p.m. to reflect the fact that Ma’amtagila Matriarch Tsastilqualus Ambers Umbas did make a speech at Centennial Square.

- UVic students.

- Xo, Elizabeth May’s dog.

- Brad Thom from the UVic Native Students’ Union.

- Demonstrators hold up their signs at the third annual Women’s March Victoria. Photo by Anna Dodd, Editor-in-Chief.

- Victoria Women’s March organizers.