A long road ahead

International students all over the world share the anguish of being cash cows for their host societies. When the UVic Board of Governors approved another 15 per cent tuition raise for international students on March 26 — following a 20 per cent raise in 2018 — deep down there was little surprise, because we knew it was coming. The protests against the international fee hikes, from the start, were intended to serve a symbolic purpose. Coming together as a student community — domestic, Indigenous, international — surely presented a significant statement to those in authority by delaying the pushing of those buttons. Importantly, the powerful need to know what the vulnerable have to say, and the student performances on March 26 was a moving articulation.

At the same time, behind the scenes of raucous protests, lie deeper issues within the student community. Since leaving Singapore in 2014, this is my fifth year overseas as an international student — in England, and as of Fall 2018, Canada. It is obvious that the international community are irreducibly diverse in political standpoints, but often such internal tensions are not immediately apparent to Canadian society. In everyday interactions, international students often do not see eye to eye. A lot of this discrepancy, ironically, stems from what we know as a consumerist culture. Students who make up the international community come from a myriad of political contexts, including a large number of post-colonial states who inherited the British model of Social Darwinist Capitalism.

The sense of increasing financial precariousness and being blackmailed into choosing between the essentials of life are not unique to Indigenous students and internationals — although these groups bear the brunt.

For many Southeast Asian states, upon formal independence, the choice was not whether to pursue modernity as the colonizers prescribed, but how to pursue it. More a politics of survival than frivolous consumption, many local leaders strove to guarantee satisfactory living standards while standing by commitments to communal wellbeing. Sadly, the age-old practice of equitable moral reciprocity is falling apart in the face of vehement capitalist pressures. Like it or not, spending habits have become a way of evaluating someone’s worth at the expense of respecting dignity. With no radical alternative, the colonized are compelled to assert their agency through redeploying the master’s tools of individualistic competition. The colonies cannot achieve wealth unless they also colonize. More often than not, this means accepting ‘winners’ and sacrificing ‘losers’ within one’s own community.

There is great variation in the degree to which people have internalized the concept of progress. These discrepancies constitute formidable obstacles to building solidarity among internationals themselves. The idea of being superior to others based on habits, practices, and otherwise is not exclusive to white supremacy. When we fail to think carefully about our own beliefs, we fall into this trap.

At a private level of everyday conversation, it isn’t uncommon to hear internationals blaming their counterparts for simply lacking the resilience ‘to make it’. Using one’s nationality in insensitive ways is another prevalent way of speaking, as citizens who occupy ‘successful’ stories of development, especially the ‘Asian Tiger’ states, often speak about ‘undeveloped’ countries in degrading ways. Surely this way of relating to others extends beyond issues of colour. Some of my closest acquaintances and fellow internationals in England were avid supporters of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), an aggressively right-wing xenophobic party.

Students inhabit larger structures of oppression which stretch beyond their assigned categories of domestic, Indigenous, international, and otherwise. The sense of increasing financial precariousness and being blackmailed into choosing between the essentials of life are not unique to Indigenous students and internationals — although these groups bear the brunt.

What lies ahead is a more challenging task of achieving mutual recognition, where we can acknowledge one another’s humanity as equally valuable.

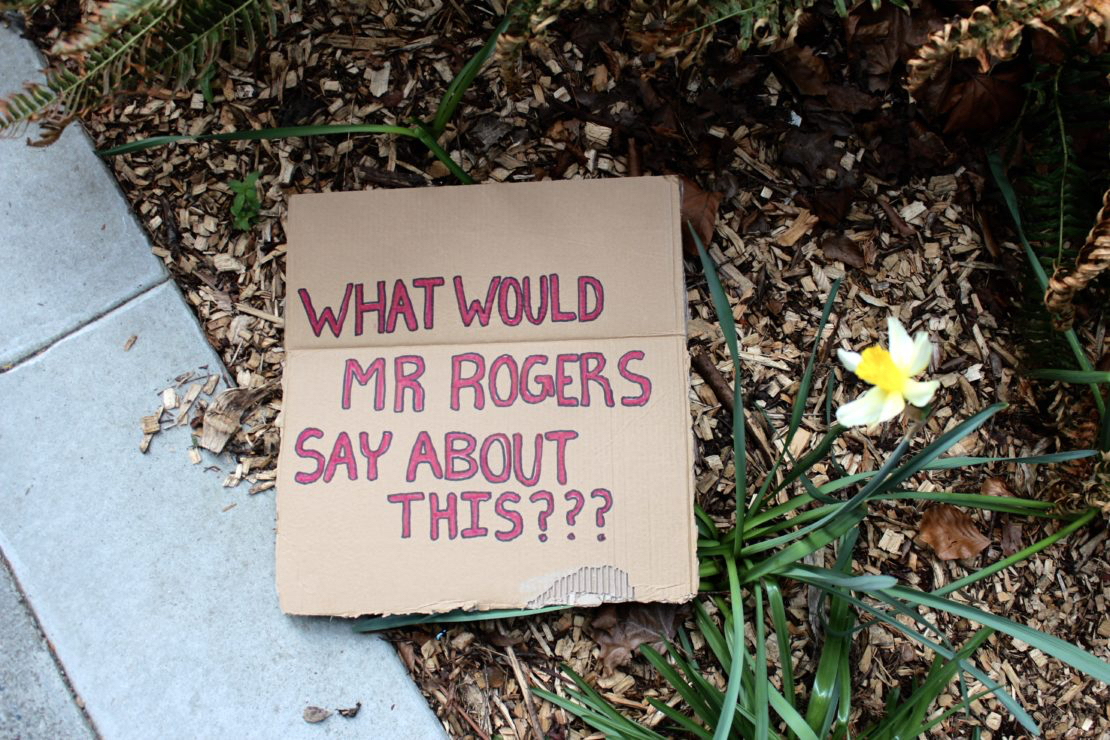

The slogan “People Over Profits” is powerful precisely because it captures this connection. Still, the student community who have devoted themselves to the resistance seem worryingly unstable relative to more powerful groups. The playing field is far from level. In this battlefield, some student groups are much more vulnerable than others. What lies ahead is a more challenging task of achieving mutual recognition, where we can acknowledge one another’s humanity as equally valuable. We strive for this when we take on roles as teaching assistants, and when we interact with fellow colleagues in our respective departments.

It is very easy to slip into nationalistic thinking when talking of which people should matter. Questions like, “What about Canadians?” or “How does this affect Canadians?” are as dangerous as they seem harmless. Sadly, this lack of imaginative charity for others comes up at many public speakers’ events, which only further marginalizes the voices of the excluded. At the same time, this problem does not only exist in Canada. Having a bounded sense of community and caring only about ‘our people’ is a problem that crosses boundaries. Hearing domestic students say that international students should be paying more — because they do not need to pay taxes — is just one example of falling back on the idea of a ‘Canadian people’. Besides, this is a hopelessly naive way of analysing the situation. Just ask the international students who have to miss classes for work whether tax exemption has made their lives easier, and we will know that policies are pretentious. These kinds of disagreements are not just between but within categories of students who are discriminated against by the institution.

What would it take to recognize that society as a whole has been psychologically circumcised? The ways we were taught to think deserve a whole lot more consideration. Being able to reflect critically on ourselves is of course easier said than done, but we can work towards it with an open mind. There are a good number amongst us who care for others tirelessly, and I’m sure we know who those precious people are. Some of us prefer to resist in quieter ways, so we owe enormous gratitude to those brave enough for open confrontation. Behind the scenes and on the frontlines, we are one but we are many.