The 2015 federal election saw the rise of Justin Trudeau to the position of Prime Minister on the back of a campaign of positivity and sweeping promises such as tax breaks for the middle class and the legalization of marijuana. While many of Trudeau’s promises have been kept, one that was abandoned was electoral reform.

Despite forming a Special Committee on electoral reform, which recommended designing a proportional representation voting system and calling a referendum to determine whether it would happen, the Liberals soon abandoned the project. Trudeau stated that electoral reform would not be part of their mandate because “a clear preference for a new electoral system, let alone a consensus has not emerged.” Thus, contrary to what was promised, voters went to the polls in 2019 with a first-past-the-post system still the order of the day.

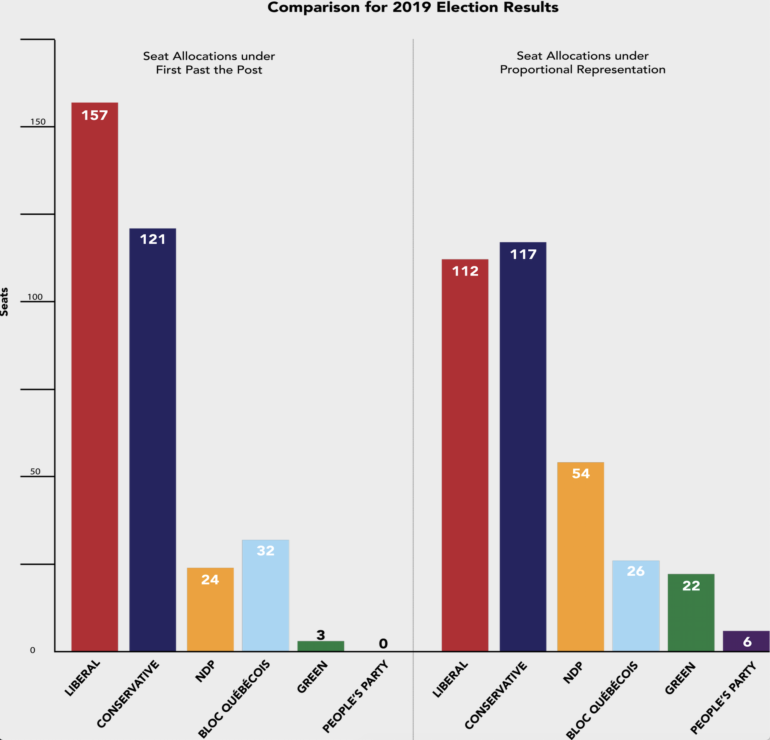

The Liberals remained the ruling party after the 2019 election, but only secured a minority government, with 157 seats. The Conservatives won 36 fewer seats than the Liberals, with 121, but failed to form government despite receiving a full percentage point more of the popular vote than the Liberals. Meanwhile, the NDP won only 24 seats and the Bloc Québécois (BQ) won 32 — even though the NDP received over twice as many votes as the BQ. The Green Party won just over a percentage point less than the BQ in the popular vote, but secured just 3 seats. The new People’s Party were shut out of Parliament with their leader, Maxime Bernier, failing to even win his own seat.

While we know these results were produced by our first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system, how exactly does this system work? Under FPTP, Canada is divided into 338 ridings in which Canadians vote for their preferred local candidate. The local candidate who receives the most votes in that riding becomes that riding’s Member of Parliament (MP). The party that wins the most ridings is given the chance to form government. Due to the “winner-take-all” nature of the system, in which the candidate who finishes second gets nothing, the number of seats a party wins in Parliament often doesn’t match the percentage of the popular vote they secure.

We’ve painted a pretty favourable picture of proportional representation so far, but it isn’t all sunshine and democracy.

Proportional representation is an alternative electoral system designed to fix this discrepancy between votes and seats. While there are many different variants, let’s keep it simple and explain pure proportional representation. Under this system, Canada would function as one large riding in which people vote for parties and the percentage of the vote each party receives would directly correspond with its proportion of seats. Given this, what would the impact have been on the 2019 election had voters been heading to their local polling station with straight proportional representation instead of FPTP?

In 2019, under straight proportional representation, the Conservatives would have had the first chance to form government — rather than the Liberals — but would have won four fewer seats than under FPTP. The Liberals would have seen a large drop in seats from 157 to 112. The NDP would have won 54 seats instead of 24. The Bloc would have dropped slightly from 32 to 26 seats due to the decreased importance of regional strength, while the Greens would have seen a sevenfold rise in seats from 3 to 22. Finally, the People’s Party would have been given a voice in Parliament with 6 seats.

Clearly, had Trudeau kept his 2015 promise of electoral reform, the 2019 election would have looked very different. Whether this would have been good or bad is a matter of debate. One good thing about proportional representation is that voters have more say in the makeup of Parliament. Canadians who voted for a losing party in their riding in 2019, like the 20 846 residents of Victoria who voted Green, would have directly shaped the composition of the House of Commons.

Not only would proportional representation make Parliament more representative of the desires of individual voters, it would make legislation more representative by forcing parties to work together. Smaller parties have a much greater voice and can exert influence on bigger parties in need of support for their legislation.

While proportional representation has both strengths and weaknesses, not all Canadians are willing to accept the status quo.

In the Canadian context, proportional representation could decrease the regional polarization emphasized by FPTP. On the surface, FPTP appears to allow representation of distinct regional interests. However, FPTP has been shown to have a polarizing effect. It encourages parties to campaign only in ridings where they have a chance of winning. This means that regions of the country become heavily associated with the party that typically wins there, for example, the Conservative Party in the Prairies and the Liberals in the Maritimes. FPTP also increases regionalism by favouring smaller parties with regionally concentrated support — just look at the success of the BQ versus the Greens.

We’ve painted a pretty favourable picture of proportional representation so far, but it isn’t all sunshine and democracy. Since there is less of an incentive to achieve broad appeal, proportional representation can lead to smaller parties, who may have extremist beliefs, exerting a disproportionate influence on policy if larger parties require their support to form a coalition government or even to pass a piece of legislation. For example, the People’s Party would have won six seats under straight proportional representation and might have significant leverage if a larger party was dependent on their cooperation.

Finally, proportional representation doesn’t guarantee the efficiency associated with majority governments in FPTP, potentially making it harder to pass legislation and leading to government paralysis.

While proportional representation has both strengths and weaknesses, not all Canadians are willing to accept the status quo. The advocacy group Fair Vote BC is challenging the voting system under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, arguing that FPTP denies the right of Canadians to effective representation, meaningful participation, and fair and legitimate elections. Fair Vote BC is also claiming that FPTP discriminates against voters based on political beliefs and against candidates based on racial and gendered grounds. While this challenge is unlikely to be successful, it represents one of the many consequences of Trudeau’s broken promise. Every system has its pros and cons, but Canadians at least deserve to have a wider conversation about the electoral system that shapes our governments — a conversation we were promised four years ago.