Dr. Caroline Cameron leads team of researchers to combat ancient disease

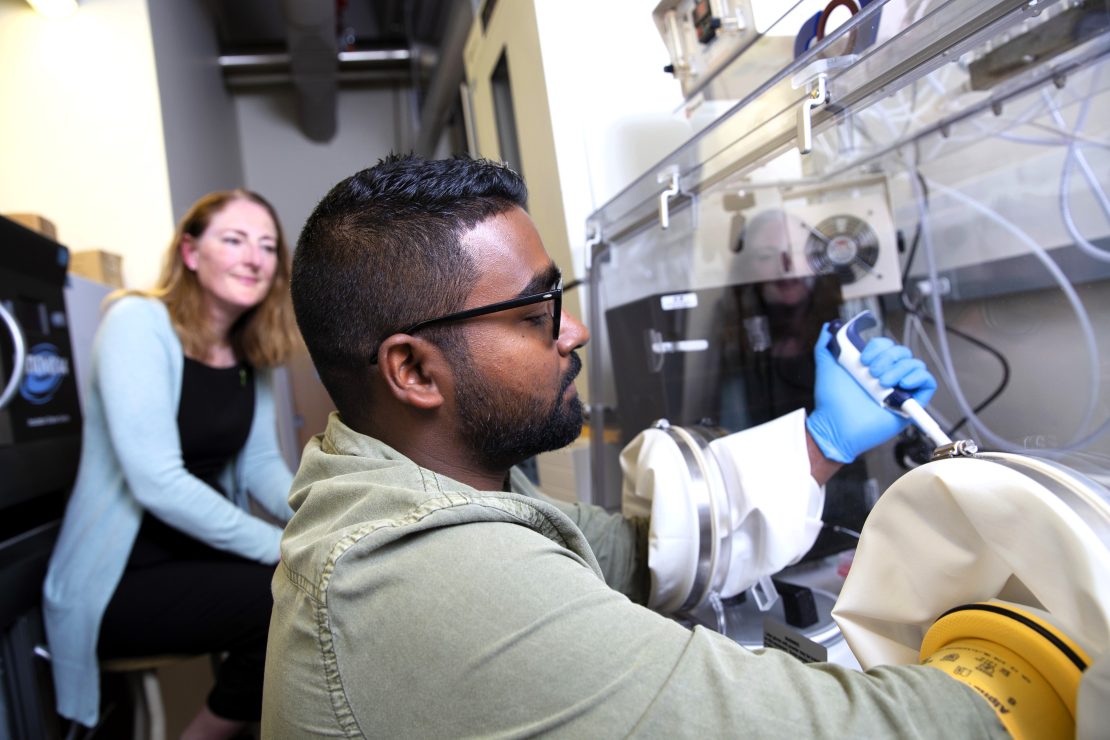

Photo courtesy of Dr. Caroline Cameron.

Dr. Caroline Cameron, researcher and professor in the department of biochemistry and microbiology at the University of Victoria, is leading a team of international researchers to develop a vaccine for syphilis.

While the exact origin of syphilis is still debated amongst scholars, the first recorded outbreak was from the Battle of Fornovo in 1495, which occurred after King Charles VIII of France invaded Italy in September 1494. Despite being centuries old, syphilis cases are rising both in Canada and around the world. According to the Government of Canada, rates of infectious syphilis have increased by 109 per cent in the last four years, and congenital syphilis, which is passed to a fetus during pregnancy, has seen a 599 per cent increase. In 2022 alone, there were almost 14 000 reported cases of infectious syphilis in Canada, which is approximately 36.1 cases per 100 000 people.

In an interview with the Martlet, Cameron explained that the rise in syphilis cases is multifactorial.

“In the 1980s, in general this disease was close to being able to be eliminated because the numbers were dropping so much. … That was partially because HIV was such a significant disease and so condom use was very high.”

“So during the 1980s,” Cameron continued, “people that were working on this disease started working on other things, because it was accepted that we wouldn’t need to work on this disease anymore, so that’s part of why there’s a dearth of investigators.”

“However, as HIV has become a manageable disease since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, condom use has decreased, causing rates of syphilis cases to increase,” said Cameron. “From a public health standpoint, it’s very important to take this disease seriously.”

Not only does having syphilis increase the risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), if left untreated, it can cause complications even decades after infection, negatively affecting various organs such as the heart, brain, and liver. Untreated congenital syphilis can have severe complications for infants, including neonatal death, stillbirth, and lifelong health problems.

There are also technical reasons for the lack of research on syphilis.

“We only recently were able to start culturing this bacterium. … You need to be able to have a source of the bacteria to be able to study it, but even now that we can culture and in vitro, it’s very difficult to grow it and you don’t get many bacteria, so it’s hard to work on.”

Cameron has dedicated her research to helping people, especially those from underrepresented groups whose voices are often overlooked or ignored. Cameron explained that syphilis and other STIs disproportionately affect people who do not have access to proper healthcare, making these diseases particularly prevalent in middle and low-income countries.

While many labs work on the disease itself, Cameron’s is the only lab in Canada currently studying the bacterium that causes syphilis. Cameron began studying syphilis almost 30 years ago during her post-doctoral research at the University of Washington, which she describes as a “hub for research on sexual and reproductive health and STI research.”

Though Cameron is the lead researcher, her team is also invaluable to the process.

“I am completely dependent upon my lab personnel,” she told the Martlet. “They do all of the actual experimentation, and it’s incredibly important to have a strong research team and that’s luckily what I have here, including graduate students and undergraduate students from UVic, and postdocs and lab technicians that went through the UVic program.”

One of the most meaningful aspects of Cameron’s work is training the next generation of scientists through her research.

“Seeing their enthusiasm — that to me is success,” she said. Beyond this, she is also hopeful that the research will be successful. Though they are not the only lab developing a vaccine for syphilis, Cameron believes that regardless of who develops this vaccine, it will positively benefit public health.

“It feels like you’re contributing to something good, and it’s a real good thing,” Cameron said.

Cameron’s research has been supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) since 2002, but recently the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which is part of the NIH, has begun supporting Cameron’s research with an additional five year grant of $7.8 million USD.