An Offbeat by CFUV review

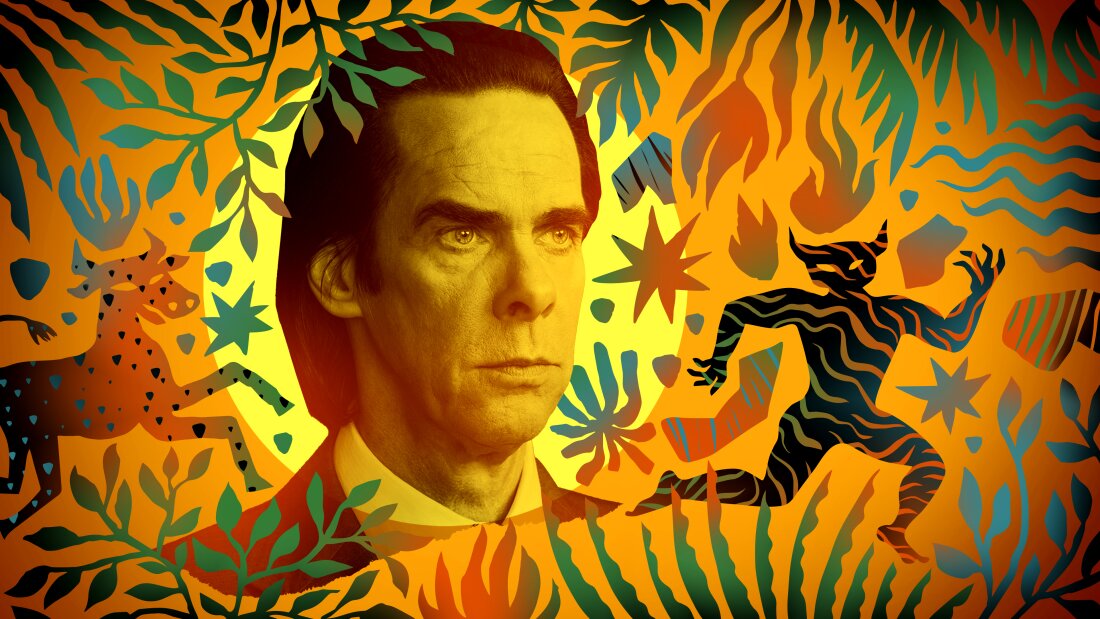

Photo via NPR.

On his new record Wild God, Nick Cave’s melancholy is transfigured into joy.

In order to fully comprehend the self-mythical madness of Wild God, one must first understand its place as an end-point in a trilogy of records charting Cave’s grieving process following the sudden death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur, in 2015.

The centrepiece of the record, “Joy,” begins with the wistful piano and ambient textures of Cave’s 2019 album Ghosteen, before introducing a hymnal trumpet part that seems to represent the heavenly presence of his late son. He opens the song without beating around the bush: “I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head; I felt someone in my family was dead.”

Cave is visited by Arthur, in the form of a gargantuan “flaming boy” with “giant sneakers.” He begs the figure for mercy, as his vocal delivery swings further and further from beat, before this haunted figure offers him relief: “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy.” A choir joins the song, as the trumpets’ angelic but melancholic noodling is remediated into joy. “Joy” is a choice Cave is finally allowed to make.

Arthur’s passing haunts the avant-garde darkness of Cave’s 2016 album Skeleton Tree –– which was in production at the time of Arthur’s passing –– while 2019’s minimalist masterpiece Ghosteen is a grief-stricken eulogy of scriptural proportion. While Cave is never one to shy away from biblical platitudes and affected melodrama, the tragedy of his son’s death richly bolsters his alienating, hypermasculine, histrionic yet literary songwriting.

On his earlier records, Cave revealed a falsetto when he stripped away the stadium-ready arrangements he’s thrived on for the past two decades. The effect, in Ghosteen, was that the record evoked more than empathy; it evoked grief in totality. It makes the insertion of oneself into the records seem pointless in the face of Cave’s epic grief.

After the release of Ghosteen, it seemed that Cave, who once yelped gothic blues-rocky poems of blowjobs, blasphemy, and Byron over industrial noise, had evolved into an artist of distinct vulnerability in exchange for his bombast –– and in exchange for his late son.

But, five years after Ghosteen, Cave has found harmony with the ghost that haunts him. On Wild God, Cave finally turns his epic melancholy into a new polytheistic joy –– not to be confused with happiness (as he wrote on his blog, Red Hand Diaries #298). Wild God is filled with pomp, passion, rock and roll, and an ageless artistic spark; and not without abandoning the carnage that made his previous two records with the Bad Seeds so markedly powerful.

From the outset, “Song of the Lake” hits with the off-kilter vivacity his best songs are known for; like a late-era Scott Walker crooning over Suicide instrumentals arranged by a stoned George Martin. The moody ambient synths of Ghosteen are upgraded into full-on orchestra sounds. Nick Cave, who’s active touring life was curtailed by tragedy and pandemic, has carved out a sound begging to be played live with the Bad Seeds in full-band formation.

“Nevermind, nevermind,” he refrains throughout an interpolation of “Humpty Dumpty” –– both unsure whether he’ll ever be put back together and blasé about whether a rebuilt self is even worth pursuing. He’s gonna deliver his off-beat punk-tenor through a dazzlingly massive art rock song, regardless.

As much as Wild God is a triumphant ascension from the abyss, it does not want the faithful listener to forget its context, even if throwback Abattoir Blues-esque single like “Frogs” suggest otherwise.

Wild God is not as cathartic as Ghosteen nor as chilling and prophetic as Skeleton Tree, and veers much closer to the cryptic ballads and gothic gospel rock of his earlier catalogue. But Cave refuses to return to form outright, instead offering listeners a window into a hopeful after-part; not acceptance, per se, but coexistence with calamity –– allowing the pain and euphoria of the past to blur together.

Not many artists are gifted with such strong late-period work. Cave, however, has always been as brash as a disenfranchised teenager with the wisdom of a bookish elder. Now, on Wild God, he uses his wisdom and provocative ways to express something open-hearted, vulnerable, universally human –– and, finally, joyous once again.