If you were to look for traces of the Emily on campus today, they wouldn’t be easy to find. The publication — a feminist newspaper produced on campus in the 1980s and 90s — is only briefly referenced on the Gender Empowerment Centre’s (GEM) website as “Thirdspace,” the name it was rebranded under around 2000. There are only a few people who know where to look — deep in the Martlet archives, or on a huge online database. But there’s one person who knows exactly where the Emily lies: Mack Costello, a first-year writing major and work study student at the GEM.

Costello first encountered the Emily last November, as part of her work for the GEM.

“One of the things that the GEM is interested in doing is looking back at our archives,” she said. “I started looking and reading the Emily, making recording notes of all of the different articles.”

Making her way through old issues of the Emily — which ran about four or five times a year between 1982 and 1999 — Costello carefully reads every article. Often, she will make a note of pieces that spark her interest, so that the GEM can potentially circulate them on social media or hang copies around their space in the Student Union Building.

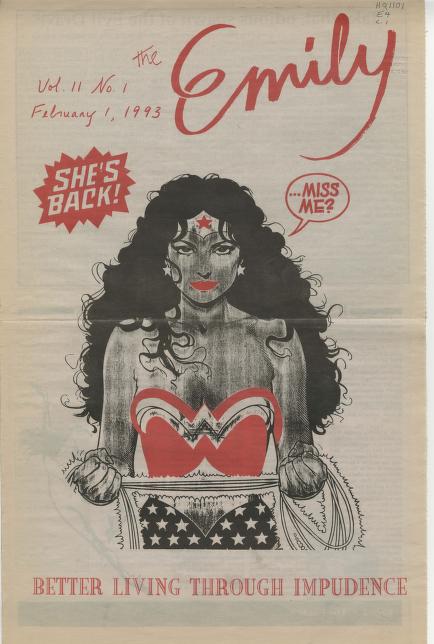

In the very first issue of the Emily, from Oct. 28, 1982, there is an editorial that attributes the naming of the publication in recognition of significant Emilys in history — Emily Brontë, Emily Dickenson, Emily Carr, Emily Murphy, and Emily Pankhurst are all specifically noted.

“Although communicating is essential to the feminist movement, we often become so wrapped up in our lives that we fail to listen to each other,” reads the editorial. “The Emily is the means that we have chosen to open up lines of communication.”

Into the archives

The Emily often printed art, poetry, reviews, lists of community resources, highlights from moments in history, and pieces on topical issues through a feminist, gender-focused lens. Some, like “The Emily’s Top Nine List: Random Acts of Rebellion,” took a tongue-in-cheek look at gendered perceptions of body language in public spaces (number two: sit on that BC Transit bus (if they ever start running again) like a real man).

“There’s pretty much no topic, whether we would view it as feminist or anti-feminist today, that they didn’t breach,” said Costello.

One such topic Costello was surprised to see make recurring appearances in the Emily was militarism and nuclear warfare. Most of these pieces were rooted in the Cold War, which was ongoing for the first decade of the Emily’s publication.

“There were a lot of articles on militarism and its effects on women and the environment, and I think that those are really interesting because they read as things that could be very relevant today,” said Costello.

“[It’s] very interesting to hear the perspective from that era, [which was] the first time when people were thinking about these issues as being all connected to one another.”

To Costello, the Emily appears to be focused on being a resource and outlet for those involved in UVic’s Women’s Centre and Department of Gender Studies as both of the programs grew.

But what did the Emily mean to those who were behind its publication? After 20 years, Costello and the other members of the GEM have only the words left behind connecting them to the writers and editors of the Emily.

A paper for people on the fringes

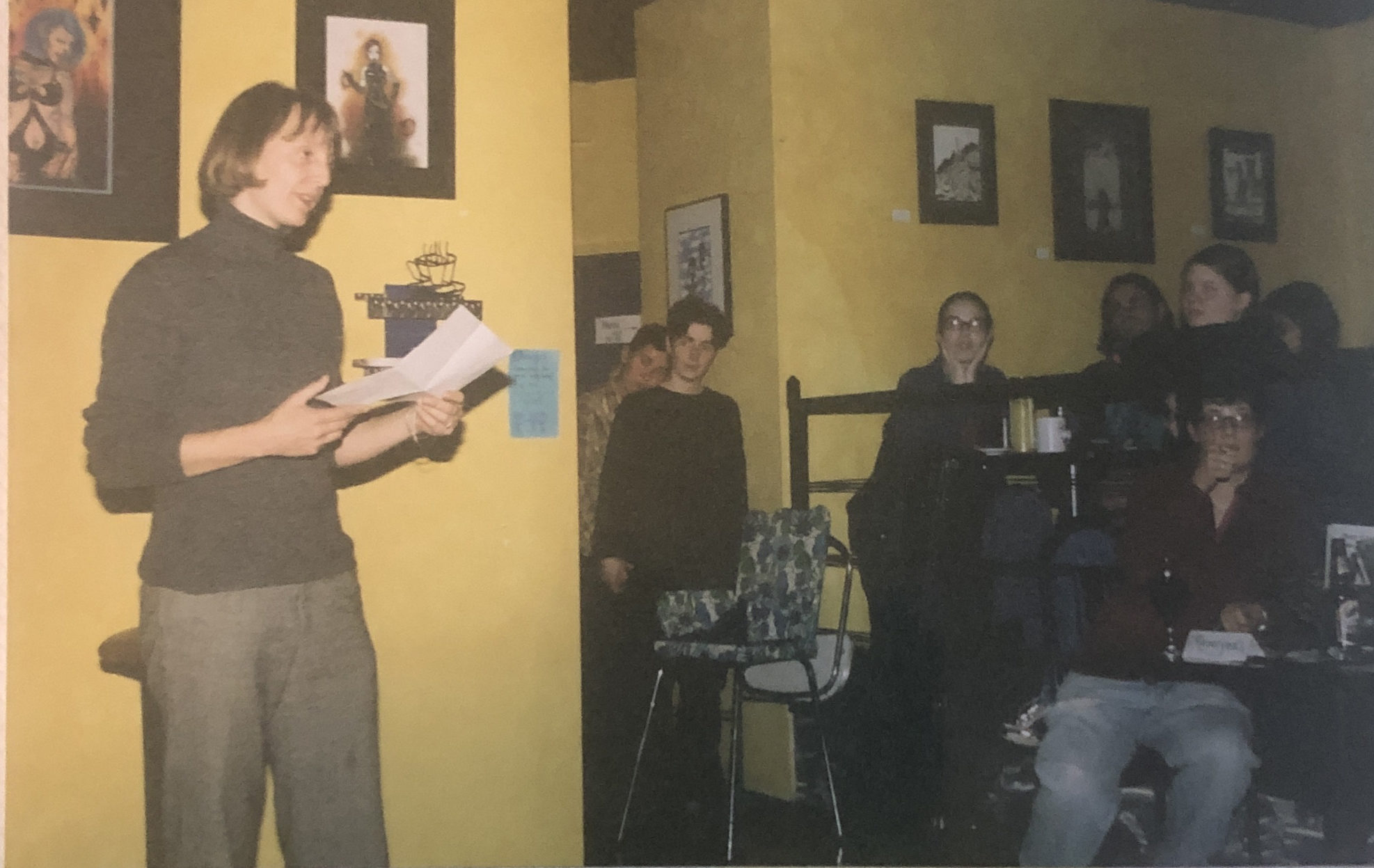

The year was 1997. Lydia Del Bianco was a first-year writing student, much like Costello is now, interested in volunteering with the Women’s Centre. In her first few years at UVic, she wrote for the Emily — and discovered she had a knack for designing the paper’s layout.

During her last two years at UVic, Del Bianco decided to apply for the Emily’s co-editor work study position. She got the job, and served as co-editor alongside another undergraduate student pursuing a degree in history and gender studies, Lisa Helps — who many know today as the mayor of Victoria.

Like many of the Emily’s writers, Del Bianco would often contribute essays initially written for her classes. But her first piece, one that has stuck with her for over 20 years, was based on an interview she did with a local Holocaust survivor.

“It was pretty emotional, it was really amazing to talk to her and see her perspective and what she went through,” Del Bianco said. “I’ve never forgotten that.”

Del Bianco enjoyed her time writing and editing the Emily, especially the ways in which it allowed her to express herself as a writer and an artist. But, she said, the Emily held a significance far beyond that.

“It was a way for other writers and artists to connect with each other and create something that was entirely for us — it was for feminists, it was for queer people, it was for all the people on the fringes who weren’t represented at all really on campus much,” said Del Bianco.

Although Del Bianco had written for the Martlet — which made its own radical commentary on gender in the 1990s — she felt it was hindered by a majority of white, male voices in the publication’s pages.

The Emily, though printed through the Martlet and preserved in its archives, was part of the Women’s Publication Network, which published the Emily and its sister publication focused on women of colour, Ain’t I A Woman?. These two publications merged in 2000 under the leadership of Del Bianco, forming Thirdspace. Although Thirdspace is no longer in print, the Women’s Centre renamed itself after the publication in 2016, before renaming itself again to the Gender Empowerment Centre in 2019.

First and foremost, Del Bianco said, the Emily was a feminist newspaper, focussed on giving women’s voices a platform. Contributions were open to anyone, and decisions were made by consensus.

Although layout for the paper was done digitally, the pages would then be printed off and pasted up prior to publication. Members of the Emily spent weekends borrowing the Martlet offices to produce their latest issue.

“We’d be working around the clock,” said Del Bianco. “We had to do it on the weekends, because otherwise they were using the office.”

For its time, she feels the Emily was progressive — although Del Bianco acknowledges that feminism in the 1990s was often white feminism, without much of the intersectionality practiced by most feminists today. There were internal disputes around the inclusion of transgender voices, particularly individuals who had transitioned to male while working at the Women’s Centre.

It was a desire to increase the paper’s intersectional scope that led to the name Thirdspace, which members of the Women’s Centre hoped would encompass all members of the Women’s Publication Network.

Reading the Emily in a modern context, Costello said that influences of second-wave feminism are pretty evident at some points in the publication.

“There were a lot of articles dealing with issues that were very relevant at the time but today read as just not applicable to our interpretations of feminism and what it means to be a feminist,” Costello said.

Del Bianco agrees — or in the very least, hopes — that an issue of the Emily produced today would look very different.

“Things have really shifted now,” she said. “I think a lot of the things that we put in there might be kind of cringey now, cause it’s old fashioned in a way.”

The Emily’s legacy

Over 20 years after the last issue of the Emily went to print, Del Bianco went to visit Anna Isaacs, one of the many former writers for the Emily with whom she is still in touch today. Isaacs had found copies of old editions of the Emily they had worked on together.

“It meant a lot to me — I always look back at that as my favourite thing that I did at school,” Del Bianco said.

“[The Emily] probably actually benefited me way more in the long run than actually getting my degree because of the friends it brought together and the good work that we did trying to uplift people.”

Del Bianco is now a graphic designer, a passion she discovered in her time poring over the Emily’s layout.

Although Costello doesn’t feel that a full revival of the Emily is in the cards, the GEM is looking into launching a blog like the Emily on their website. In the meantime, they’re also working to decorate their newly-renovated library with articles from the Emily and publishing images of old issues on social media.

Through this, Costello said, the spirit of the Emily might live on — a voice, a community, a sense of purpose for those marginalized by patriarchal systems.