There’s this theory when it comes to examining Art with a capital A called the “Death of the Author.” It’s the idea that once a piece of Art is put out into the world, the author is irrelevant. All that matters is the Art and how the audience gains their own meaning from it.

You usually see this theory mentioned when a creator is questioned for being a terrible person but you find yourself still drawn to the Art for some reason. It brings up the question of distance between the art and the artist. I do think that this theory has some value when examining Art, but I think that the Author and the Art are inherently linked on some level. Sometimes, something about the Art makes more sense when you learn about the Author. That’s the angle that Sculpture in Canada: A History takes when examining the history of sculptures in Canada, and the book greatly benefits from this approach.

Sculpture in Canada: A History traces the lineage of sculptures from the late Pleistocene epoch (125 000 years ago) all the way to the present. Author Maria Tippett doesn’t linger too long on the pre-colonial times, which I was a little disappointed by. However, Tippett mentions in the introduction that she is not Indigenous and doesn’t separate First Nations art into different chapters, allowing them to stand against the colonial pieces of art. The First Nation art she does talk about comes after after first contact, which is interesting in itself.

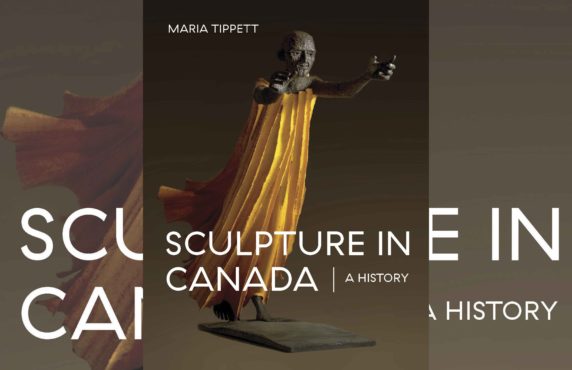

In a general discussion of Canadian Art, the focus is usually on paintings, such as Emily Carr or the Group of Seven. Sculptures, despite being an artform that has been in Canada for hundreds of thousands of years, is generally overlooked. Sculptures can vary from traditional First Nation carvings, statues, or a pile of 1 000 000 pennies. All of these have stories behind them, for what the artist wanted to do or what conventions they wanted to break, or how their art was received by the public. This book provides an fascinating and incredible introduction into Canada’s oldest art form.

Photo Provided

The book is split into eight different parts, chronicling eight different timelines. For example, chapter two focuses on sculpture from the New Colonists, which was mostly inspired from British and French styles, and chapter seven focuses on sculptures made for the 1967 World Expo. As a cultural historian, Tippett pays great attention to work and life of the artists, as well as the economic, social and political context surrounding the art. In the book, she explains who the artists were, what inspired them, and then provides a picture of the sculpture. I find that this approach paints a much better picture of the overall history of sculptures by connecting the works to the artists and contexts in which these pieces of art were made.

Because of this connection, the sections paint a clearer and more interesting picture of the art, at least for me. I find that this approach also allows for an interesting and new perspective on certain points of history, like the World Wars or the World Expo or the reaction to the potlatch ban.

Tippett also brings up the initial response and criticism to the sculptures, and it’s interesting to read how people responded to to the pieces at the time and how they respond to them now. I find that it also adds a bit of perspective to the pictured examples. You see the physical example and then compare it to the initial criticism. It’s an interesting angle to take — one that ultimately adds depth to the observation of historical art.

Sculpture in Canada is a mix between approachable and academic; it’s balanced between really informative and a good entry point. It’s a relatively easy read, but there’s a lot to get through at times — I’d recommend pacing the book out a bit if you plan to read it.

So, if you are looking for some additional reading for a class, wanting to understand the history of art through these incredible sculptures, or just trying to see history through a different perspective, I recommend this book.