The privatization of healthcare is a threat to the fundamental rights of Canadians

Photo by Fernanda Solorza.

During my second year at university, I took a course in biological anthropology. Although I learned plenty, my strongest memory is of one Tuesday lecture when we looked at buried remains of early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Noting the evident love with which they were buried, the professor pointed to healed fractures and injuries, explaining that such care and compassion for the injured marked the beginning of our society.

I’m baffled by how our values have changed since the emergence of organized societies. The rise of capitalism and the privatization of services has led to segregation and the exploitation of the most vulnerable sectors of society. Canadians take pride in their healthcare system, but mismanagement of this system has led to advocacy for private healthcare. Dr. Brian Day, former president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) launched a court lawsuit against the B.C. government in 2009 against certain sectors of the Medicare Protection Act, advocating for private healthcare for Canadians. His legal battle stretched 14 years, and was ultimately dismissed by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2023.

However, shortly after, Dr. Kathleen Ross, the new and active director of the CMA, began a series of cross-country consultations to discuss the role of private health care in Canada’s publicly funded system.

When addressing the tension of (even partially) privatizing a public system, it is imperative to point out that privatizing healthcare not only judicially violates the Canadian Health Act (CHA) by compromising the comprehensiveness and universality of healthcare systems in Canada, but morally violates fundamental human rights. A cost for services puts more Canadians at a disadvantage than would benefit.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of themself and their family, including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services.”

There are certain aspects and sectors in society that simply should not be managed for profit. The notion that someone’s health should depend on their wealth is fundamentally unjust. I come from Mexico, a country where a dual healthcare system is in place. A dual or two-tier system refers to a model where both public and private healthcare services co-exist. This system is morally unfair and leads to exploitation and abuse.

My parents are medical practitioners in Mexico. I have heard anecdotes from their personal experience mentioning how their colleagues work in both public and private sectors and use their status as professionals to misinform and redirect patients to their private offices to upcharge for their services. As an OB-GYN, my father is concerned with the number of pregnant people who, under the misdirection of money-oriented practitioners, pay for cesarean sections instead of opting for the safer and less invasive natural birth.

These situations are not unfamiliar in Canada either. In 2017, The Globe and Mail led an investigation that exposed many B.C. doctors who double-billed for their services. This issue has not stopped.

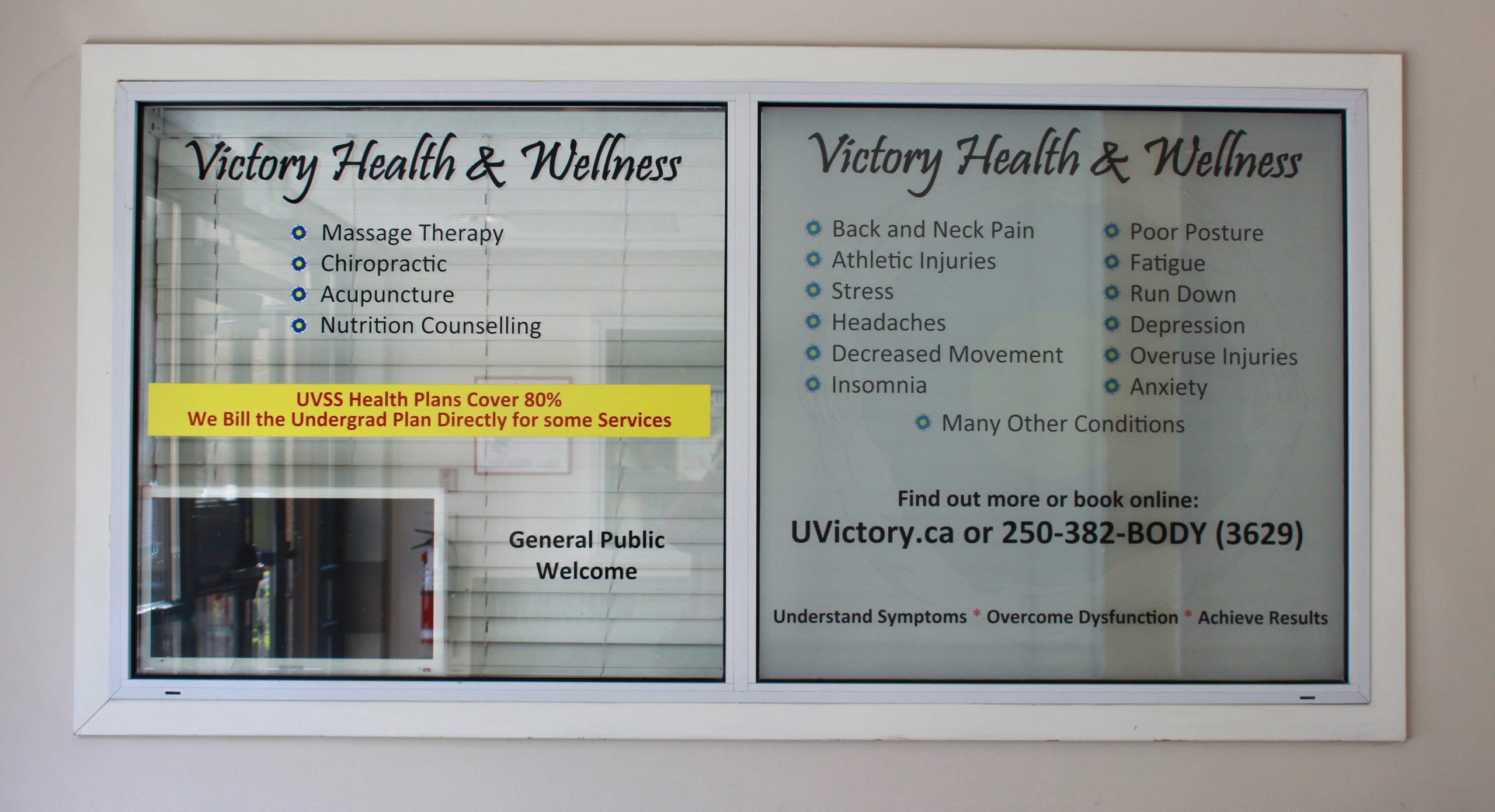

Although Canada is not officially a dual system, certain provinces like B.C. allow private clinics to offer services that are not covered under the Canada Health Act. That’s the case of Cambie Surgery Centre in Vancouver, a clinic founded by Dr. Brian Day, who is a vocal advocate for the privatization of healthcare.

When people cannot afford necessary medical care, or are forced to make impossible choices about their health, it leads to preventable suffering and death — outcomes that a compassionate society should not tolerate. By making healthcare public, we affirm the intrinsic value of every human life, ensuring that no one is left behind.

Moreover, a public healthcare system is more efficient and cost-effective, as it fosters a healthier population overall. For example, vaccine programs reduce the need for treatments and hospitalizations, which are significantly more expensive. Regular check-ups and cancer screenings detect diseases at earlier, more treatable stages, reducing costs overall and improving the patient’s survival rate and quality of life. When people have access to regular check-ups, preventive care, and early treatment, the prevalence of severe and chronic illnesses decreases. This not only improves individual quality of life but also reduces the long-term burden on the healthcare system. In a public system, the focus can shift from treating illnesses to promoting wellness, leading to a more productive and resilient society. Healthy people can work and produce more than injured or ill individuals.

Critics argue that public healthcare systems can lead to longer wait times and decreased quality of care. After losing the lawsuit, Dr. Brian Day stated to CBC News that “Wealthy Canadians have always gone down to the United States [for care], but where do middle-income and lower-income Canadians go? The answer is they’re not allowed to go anywhere. They stay and suffer and die on wait lists.” However, these long wait times are often the result of underfunding and mismanagement rather than inherent flaws in public healthcare. Additionally, it has been proven that privately-funded healthcare doesn’t solve this issue.

Australia expanded private insurance and found that these changes did not decrease wait times. Rather, in regions where private insurance was most often used, wait times in the public sector rose as resources, personnel, and funding were diverted to the private sector, leaving the public sector with greater challenges in meeting patient needs efficiently. Additionally, the argument against public healthcare based on potential wait times ignores the reality that millions of people in private healthcare systems, like the U.S., currently face indefinite wait times because they simply cannot afford care.

If Canada’s healthcare system changes to a dual or fully private system, it would mark a major drawback in its commitment to equality, efficiency, and the well-being of all Canadian residents. Certain flaws in the public system still need to be resolved, such as underfunding or lack of doctors, but those issues will not be solved by segregating the population between those who can afford healthcare and those who can’t. People should always be placed over profits. Canada must ensure that healthcare is a right, not a privilege.