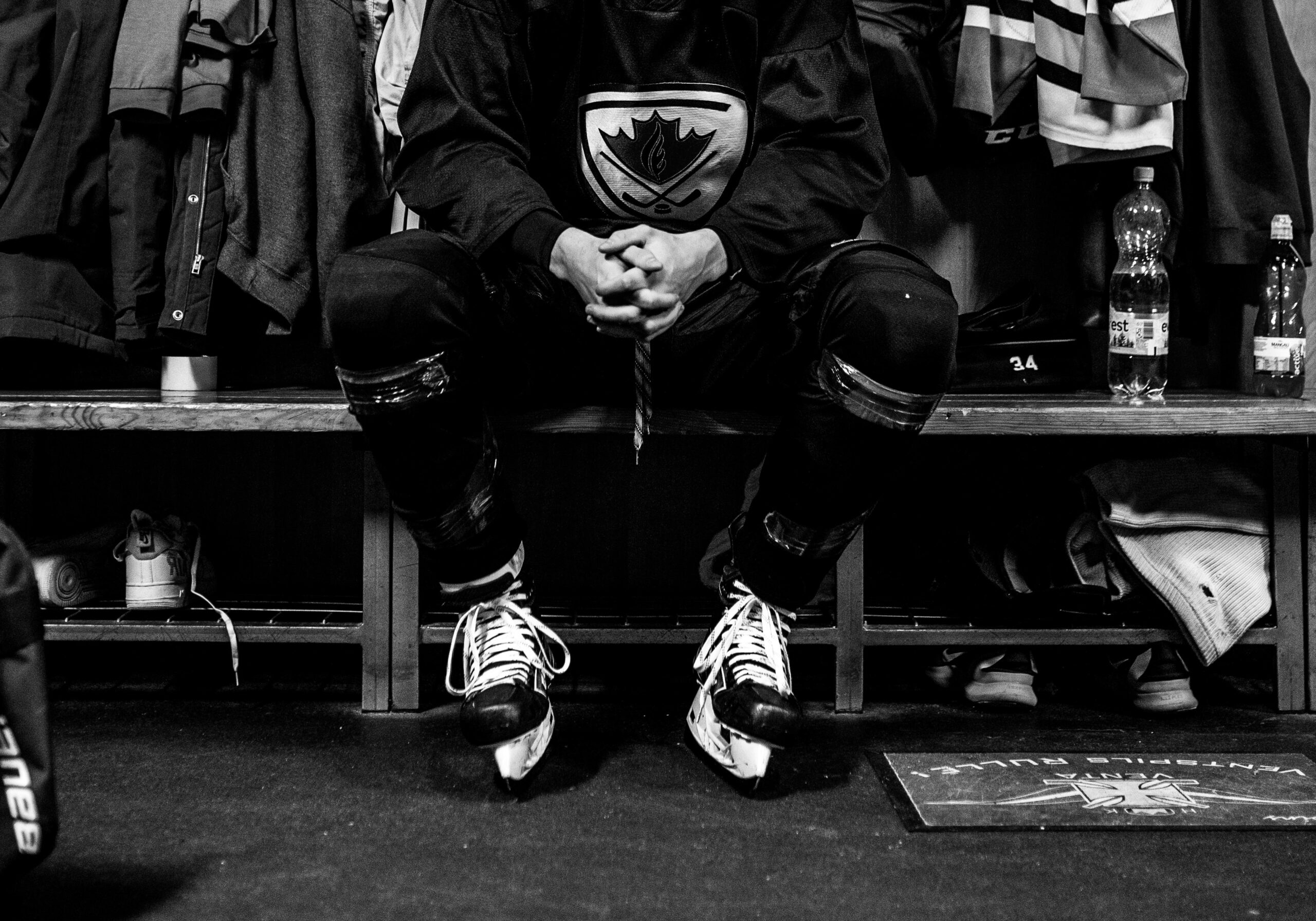

Canada’s game has an ice-cold locker room

Mark Landman via Unsplash.

TW: This article discusses sexual assault and LGBTQIA2S+ and racial harassment.

When you wear a team’s jersey, a player’s name and a number, you’re advertising that organization. That person. You’re promoting them. You want to look up to them, with pride and faith: that kid wearing a McDavid or Crosby jersey isn’t thinking about anything other than their on-ice splendour. Many will tell you that’s the ideal, to never meet your heroes and never separate the player from the performance.

Hockey is Canada’s game; many children here grew up skating before walking, shooting pucks and dreaming of the big leagues or cheering from their couches. Even me. It’s a familiarity in most households, and Canadians look at our hockey legacies with admiration and patriotism.

But so many of those same people are completely oblivious to, or ignore, the filth that oozes inside the locker rooms and on the ice and into the “hockey bro” minds and mouths of young men.

In early December, 2021, the Chicago Blackhawks organization came to a settlement with the lawyer of former Blackhawks player Kyle Beach regarding a sexual assault lawsuit during the team’s 2010 Stanley Cup run.

Beach alleges he was not only threatened and harassed physically and mentally by his own assistant coach but completely sidelined by his teammates — they ignored his suffering, some excusing it to focus on their team’s advancement but also directly contributing to it with anti-gay slurs and berating him. Some players even claimed the events to be unknown to them afterwards.

The very brothers he found on the ice turned on him and acted dumb in favour of a hunk of metal.

Following the public release of the alleged acts against Beach, many Blackhawks fans became understandably appalled and announced disgust with the organization, ceasing their support.

But Beach’s case is not an isolated one and never has been.

There is a current ongoing investigation into several sexual assault cases involving the 2018 World Juniors Canada men’s team as well. This incident has been horribly handled and reported on by Hockey Canada, according to the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) which holds the tournament.

With the 2022 tournament now over, Team Canada experienced low turnout from fans concerned with high ticket prices and the reputation of their formerly-beloved national team. Many corporations such as Tim Hortons also withdrew their monetization of the tournament.

Minister for Sport of Canada, Pascale St-Onge, is demanding Hockey Canada reevaluate their handling of sexual assault, and for the hockey world to take a good look at themselves and strive for change. Fast.

And it better.

As an LGBTQIA+ hockey fan, rich corporations such as the National Hockey League (NHL) and Hockey Canada are terrifying: the locker rooms, stadiums, and even online forums are still very unsafe. The same goes for many fans and players of colour. These are just two recent examples of an endless list of social injustices that are dominant and even encouraged in hockey.

But we are improving.

During the 2022 Stanley Cup Playoffs, the National Hockey League Players’ Association (NHLPA) released a statement regarding racist comments directed at Colorado Avalanche’s Nazem Kadri and his family following the Avs’ third game against the St. Louis Blues. In response, the Kadri family was presented with kind words and support during the following games, posters reading “I STAND WITH NAZ.” Colorado — joined by the other playoff teams — later initiated a three-day pause to learn about racial injustice and promote equality in their fandom and spaces.

On July 19, 2021, Luke Prokop (a prospect of the Nashville Predators) became the first NHL-contracted player to come out as gay. He isn’t the first gay hockey player to exist and his openness is directly reflective of our current progress as a society and culture.

Prokop will, for sure, be an inspiration for many growing queer hockey players and fans, an example of the hockey community doing something right.

Another example is pride nights; in 2013, the Florida Panthers were the first team to hold a pride night in the NHL. During the 2021–22 season, all 32 teams had their respective celebrations. Of the large-stage men’s sports leagues in North America (MLB, NFL, NBA, MLS, and NHL), the NHL is the only sport to have every team participating so far. Major League Soccer seems to be right behind.

The normalization of the sexist, homophobic, partying, and racist vernacular and ideology in hockey locker rooms is corrupting the minds of players and “professionals” in extremely well-funded, romanticized positions who act as children’s role models and influence adults’ betting and personalities.

Not only do we as fans have the responsibility to research and support ethical practice, but these players and organizations also have the responsibility to handle injustices fairly, seriously, and with proof that they truly care about their fellow players, staff, and fans.

The hockey world is starting to change for the better, but it isn’t enough.