As humans, we talk too much.

According to a University of California study, the average person speaks up to 20 000 words a day. So, what are we talking about?

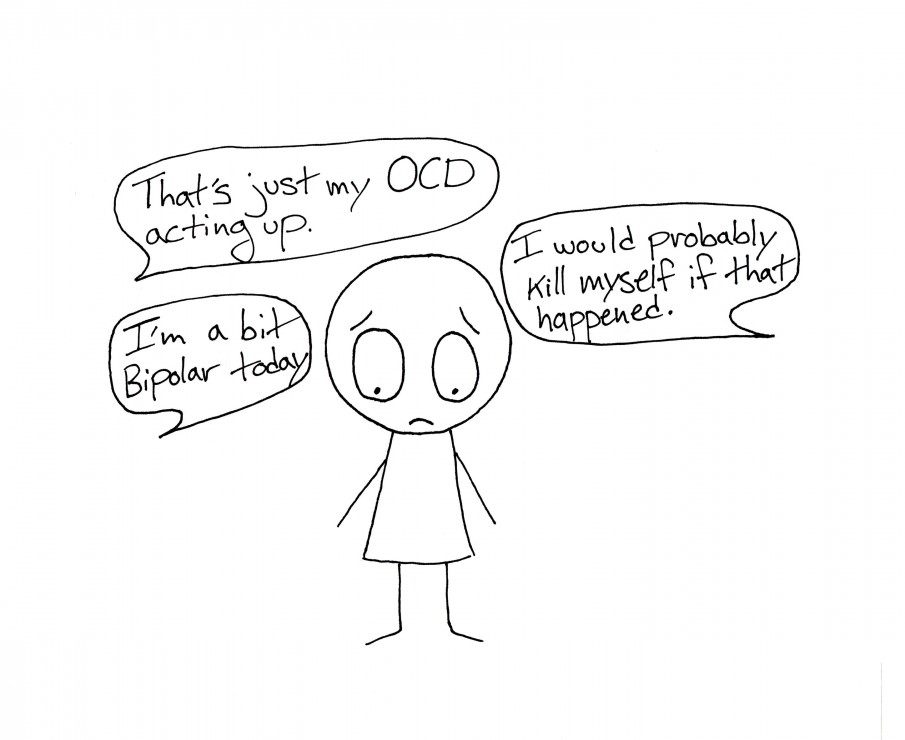

As a university student, I hear friends and classmates discuss their hot dates, weekend plans, and their favourite movies. However, I also hear many people using the language of mental health to describe common, often insignificant, situations. When we say we’re “so OCD today” because we prefer a tidy desk or dislike our potatoes touching our peas, we don’t really mean that we meet the criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

But by using and accepting these phrases in our everyday language, we trivialize the seriousness of mental health conditions.

People with mental illnesses often say that there is nothing someone can do or say that could make them feel worse than they already do. Casual jokes about mental illness only confirm the low opinion they may already feel about themselves, as the stigma they face is far worse than the illness itself. Other people’s judgments can be the greatest obstacle to living a complete and satisfying life.

Additionally, individuals suffering from mental health disorders—or those experiencing symptoms—fear telling their friends, family, and even their physicians. Rather than seeking the professional help that they need, they fear their symptoms will cause them to be judged and marginalized. According to the Canadian Medical Association, 60 per cent of individuals with a mental health condition suffer in silence. By making a joke of mental health, we fuel the stigma surrounding it and create barriers that discourage people from seeking help.

And because this language is misused so often, individuals suffering from mental health conditions cannot simply ask for support they need without people assuming they are being dramatic or seeking attention.

Before using mental health terminology for fun, consider this: medical terminology was created for use in a medical and scientific community. While its subject and application are based on human behaviour, its purpose is to understand problems and to make people’s lives better, not harder.

We’ve got to recognize that mental illness is no joke. Although some people may think I am being hypersensitive, remember this: university students are particularly vulnerable to developing mental health disorders, and most individuals report mental health symptoms between ages 15–24. Currently, three million Canadians are suffering from depression and more than half of those individuals say they’re too scared to tell someone.

The best part about all our talk is that we can choose what we talk about. We can stop trivializing these serious disorders, creating a safer environment for those struggling. It starts with each one of us. We need to be attentive to what we say and the words we use.

So the next time you’re thinking, “I have so much homework—just kill me”, take a minute and think about who you’re talking to.