Last month, UVic’s Office of Equity and Human Rights (EQHR) released a report on their second year of implementing their Sexualized Violence Prevention and Response Policy.

In the 18 months since the first report on UVic’s implementation of their new Sexualized Violence Policy (SVP) in May 2018, the rate of reports and disclosures of sexualized violence to EQHR’s intake office has increased.

Most students may not be aware that the 2019 report exists, as it was buried 88 pages deep in the Board of Governors’ September meeting minutes. We’ve broken down the highlights for you below.

Implementation by the numbers

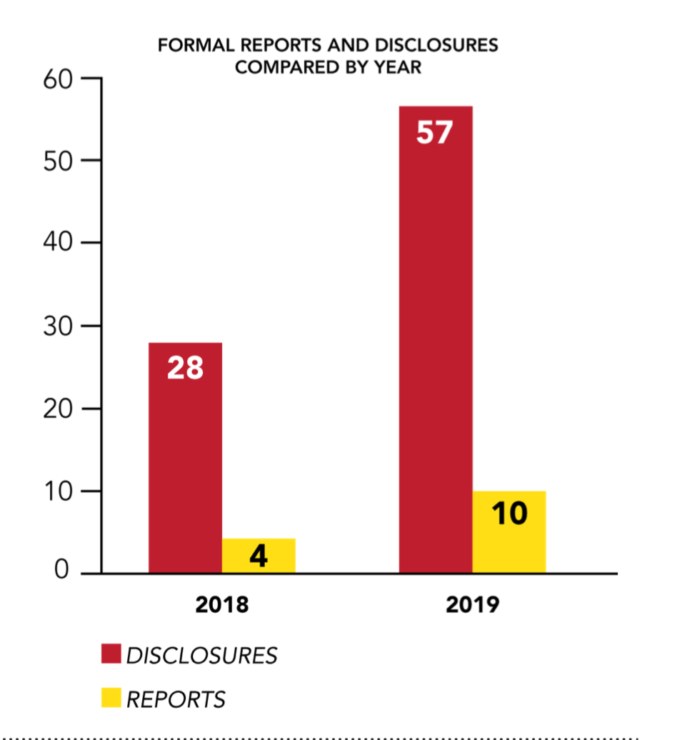

The most dramatic finding of this report was the significant increase in both formal reports and disclosures of sexualized violence. Since May 2018, 57 disclosures and 10 formal reports have been made to UVic — nearly double the 28 disclosures and four formal reports that were filed prior to the first report.

Of the 10 reports made, five led to completed investigations, four resulted in community accountability processes, and one did not proceed to an investigation at the request of the survivor.

“The numbers were bound to rise. I don’t think that that suggests there were more incidences, [just] more awareness, I think in some cases for some folks there’s more trust,” said Leah Shumka, the Sexualized Violence Prevention and Education Coordinator who has worked to create and implement workshops, resources, and the sexualized violence intake office at UVic.

Shumka expects the numbers of reports and disclosures to increase as awareness of the sexualized violence intake office becomes more widespread. Already, she says that some people who have used the office were referred by others who have used it in the past.

Although not included in the report, EQHR shared statistics with the Martlet regarding the identified gender of survivors and respondents involved in instances of sexualized violence. Of the survivors, 51 identified as female, four identified as male, and two identified as trans or non-binary. In the case of respondents, 47 were identified as male, three were identified as female, and seven did not have their gender identified. In some of these cases, survivors chose not to disclose the respondent’s gender to EQHR.

Forty-five survivors and 28 respondents involved in disclosures of sexualized violence were students, making them the largest demographic involved in campus disclosures.

Instances of sexualized violence disclosed to the intake office ranged from sexualized comments and looks (which despite not being physical, the report said “were, in some cases, extremely harmful”) to actions constituting Level 1 sexual assault under the B.C. Criminal Code. In nearly all disclosed situations, alcohol was a factor.

“All incidents involving students identified alcohol use, and in some cases heavy alcohol use, as a contributing factor,” the report states. “In some of the cases involving staff and faculty, alcohol also played a contributing role.”

Shumka said that alcohol is one of the three priority areas where she intends to create educational resources in the future, and is in the process of forming an alcohol and consent working group. Currently, there are not many existing resources for Canadian universities.

Expanding campus awareness

In terms of education and prevention, EQHR delivered 46 workshops to over 1 200 members of the university community since May 2018. Prior to that time, they hosted 39 workshops for 1 100 individuals — mostly faculty and staff.

Tools for Change, the cornerstone UVic workshop on sexualized violence alongside Bringing in the Bystander, is available as a 30-minute course online or as a three-hour seminar in person. This semester, for the first time, every student living in residence was required to complete the workshop online. Starting in January, the online workshop will be part of the New Student Orientation pre-arrival program.

The Culture and Consent working group, made up of members of the international student community and departments that work to support international students, was created to help remove cultural barriers regarding areas such as access to sexualized violence resources and different understandings of consent. Through this working group, the UVic sexualized violence resource webpage was translated into seven languages.

“International students are just as likely, if not more, to be impacted by sexualized violence,” Shumka said.

A “quick guide” brochure was also created for UVic faculty and staff, including details on sexualized violence prevention and response with a special focus on confidentiality. These brochures were sent to every faculty and unit on campus, according to Shumka. Students received postcard-sized informational guides on consent in orientation packs this year.

Not all data collected by EQHR were included in the report to the Board of Governors, which Shumka said was due to the size limitations of reports. However, she says she is working to make this information available on EQHR’s website in the near future.

Going forward

Since UVic’s SVP was launched in 2017, its implementation has not been without contention.

In September 2018, the Martlet published an investigation that detailed accounts of student survivors of sexualized violence who felt UVic’s implementation of the SVP left them without confidentiality, support, and protection.

“The policy is an improvement upon no policy,” said Riley, a former CL who shared her experiences anonymously with the Martlet for the investigation. “Better is good, but it will not be enough. We need to keep working on this, and to keep reflecting on the feedback from brave survivors whose stories were not adequately protected.”

In January 2019, a review of the first 18 months of SVP implementation was completed. The Martlet obtained an Executive Summary of this review from UVic, which highlighted challenges and areas of growth during the implementation. Additionally, the review listed 13 recommendations for change: improving collaboration, inclusivity, procedures, and resources were all suggested, though the specificity of the suggestions varied.

For the past few months, EQHR has been focusing on working on the areas for improvement identified in the review.

“A huge part of the job is collaborations,” said Shumka. “I think that not only are those collaborations getting stronger, they’re getting more dynamic.”

When asked about the work EQHR has to do going forward, Shumka said that she’s excited about the new provincial investment and focus, but that it’s a lot for her to navigate.

“I feel like there’s a lot of work [to do],” she said. “New policy, new office, new people — it just took a while for people to understand how it all fits in.”