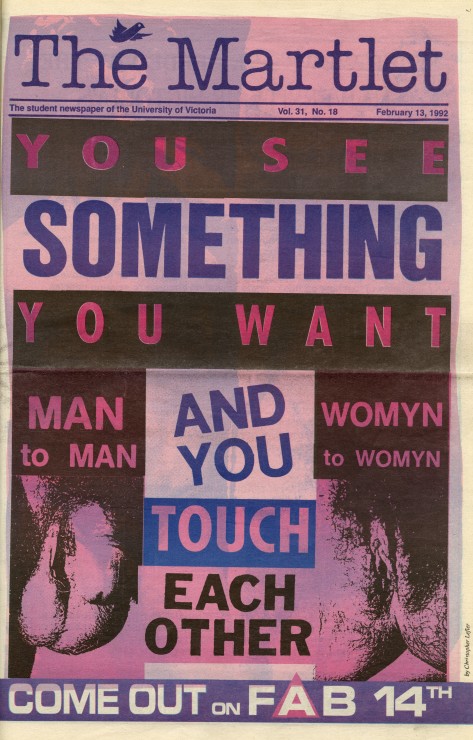

CONTENT WARNING: This story features a graphic image of genitalia.

The clouds hung low in the air at the University of Victoria on the morning of Feb. 13, 1992. It had been a bleak month, with temperatures rarely venturing above two or three degrees Celsius, and although weather data from back then is hard to find, it’s probably a safe bet to say it was raining.

In the Martlet office, it was publication day. Fresh, warm copies of the paper had been collected from the printer that morning, driven to UVic, and distributed around campus, waiting to be read.

Martlet staffers were milling around the newsroom that morning when co-editor J.B. MacKinnon walked in, bundled up against the cold. He was greeted by coworkers’ grins.

They quickly informed MacKinnon that groups of students were grabbing entire stacks of the paper and dumping them in trash cans and toilets just hours after the newspapers had hit newsstands.

Everyone in the office—MacKinnon included—was delighted.

It was on this fateful day that the Martlet published their annual ‘Queer Issue,’ dedicated entirely to the voices and concerns of what was then referred to as the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) community.

The paper was filled with stories written by and about queer students across Canada, but it was a photo on the outside that caught people’s attention.

The cover of the paper featured two images: one of a penis, the other of a vulva. The photos, which were uncensored, were accompanied by block text reading, “You see something you want and you touch each other.” The photography and the lettering were done by an artist named Christopher Lefler, an openly gay student in UVic’s Visual Arts department.

*Graphic image below*

Reaction to the cover was quick and extreme, and many wrote in to the Martlet voicing their displeasure with the explicit pictures. Reports sprung up in local newspapers, and the cover soon became legendary within the Martlet newsroom for years afterwards.

“You’re new to the Martlet?” people would ask. “Have you seen this cover?”

After seeing the cover myself in 2014, I had spent years waiting for the right time to investigate its story. I had a number of questions. How does newspaper activism change over time? Do student newspapers have a duty to push boundaries? Did the provocative cover detract from the message it was trying to convey?

A 25th anniversary of the cover’s publication offered me the chance to explore this story, and so I did. I interviewed several key figures from the Martlet in 1992, piecing together an intriguing and challenging tale of journalistic ethics, queer advocacy, and, of course, genitalia.

During an interview with MacKinnon, sitting in the same Student Union Building that housed the Martlet back in 1992, he smiles as he tells me the only question the Martlet considered when they decided to run the cover.

“We just thought, ‘why not?’”

The Martlet’s purpose, per its constitution, is “to act as an agent of constructive social change.”

MacKinnon and Alisa Gordaneer, the two co-editors responsible for volume 31 of the Martlet, wholeheartedly embraced that activist role. Throughout their time as co-editors, Gordaneer and MacKinnon wrote on a number of environmental issues — corporate and community clashes were flaring up in the forested Clayoquot Sound and nearby Mystic Vale at the time—but they took on social issues, too.

Both speak highly of the “advocacy journalism” produced by the Martlet under their stead, and both have continued to write politically throughout their writing careers.

”Student politics always felt more that you were ‘storming the barricades’ than you were if you were writing for [a more mainstream paper],” says Brett Josef Grubisic, an author and lecturer at the University of British Columbia who wrote for the Martlet in 1992. “I think it’s an advantage [student newspapers] have because of course they’re not nearly as reliant on ad revenue. You’ve got the ability to do whatever you’d like with your paper, so why not make it as political as it can be?”

“To me, the essence of journalism is independence,” MacKinnon says. “As soon as you are subjected to pressures outside of the core team that’s working journalistically, it just feels less honest to me.”

The Martlet newsroom was diverse in 1992. There was a queer caucus, which included openly gay students like Grubisic and his friend Bryan Young, who often contributed to the paper. Those students, together with Gordaneer and MacKinnon, spent their weeks before Feb. 13 developing the queer issue. It could be seen as a commendable act of alliance, but Grubisic says the differences in sexual orientation were never brought up.

“In some ways, [J.B.] and Alisa were as radical in their own way as we were,” says Grubisic. “They were certainly on board with it entirely. There was no sense that they were just tolerating us or toeing some sort of line because of their own political beliefs.”

Grubisic and Young were friends with the cover artist Lefler, who had a reputation for creating contentious art. Just a year before, he was almost expelled from UVic after setting a couch on fire as part of an art project. Along with Young, Lefler took the photos and arranged the colours and letters to bring to MacKinnon and suggest it be used for the cover.

Just as it did for the students who saw its final, published form, the cover left an immediate impression on MacKinnon.

“I do remember thinking, ‘well, that’s striking,’” MacKinnon says. “It did have a kind of brutality, almost. That’s what struck me . . . it’s very much in your face. But I was comfortable with it.”

Young was one of many involved with the taking of the photos—behind the camera, not in front—and he remembers that the nudity provoked both indifference and excitement.

“I think there was a sense among us [that] it felt like nothing,” Young says. “It felt like whatever. It’s a dick and a vagina. Who cares? But we knew that would have a big impact.”

“Big impact” is an understatement. Even before the cover was being torn off of UVic shelves, it had caused a stir within the Martlet newsroom.

Ironically, while it was the pictures that provoked the passionate response from the student body, it was the initial wording of the cover that incited the most discussion between members of the Martlet staff.

When Lefler submitted his art for the consideration of the Martlet, the genitalia was originally accompanied with the text, “You see something you want and you touch it”.

Andrew MacLeod was the Canadian University Press editor for the Martlet in 1992, and is currently an author and the Tyee’s legislative bureau chief.

“When you put a picture of genitals [on a cover] and you say, “you see something you want and you touch it” . . . it implies that consent doesn’t matter,” says MacLeod.

Some Martleteers like MacLeod were concerned insofar as they thought the wording suggested whoever was being wanted did not get a say in whether or not they were being touched.

MacLeod recalls a meeting between members of the Martlet and the Women’s Centre — now called the Third Space — where the wording of the cover was discussed. A compromise was eventually made: the phrase was changed to “You see something you want and you touch each other,” and was published alongside the photos.

For a time after the cover was published, MacKinnon believed that the change of wording was the “greatest sin” he had committed as co-editor.

“Like the people who raged against the image that was finally printed, we raged against the image that wasn’t,” he said at the time. “[The] boundaries of support for the artist only extended as far as the support for his art.”

But MacKinnon says he has mellowed considerably in the years since. While he admits that he wouldn’t have changed the wording on the cover if he had had absolute power in the newsroom, he is grateful that he didn’t have the authority to do so.

“I think that [old mindset] reflects maybe the closest thing to my personal perspective on it,” MacKinnon says, speaking slowly and thoughtfully. “[But] during that year there were many, many times where I think the Martlet benefitted from the collaborative approach we were taking — in the atmosphere of the place, and decisions we made, and all kinds of things.”

The issue of consent was not the only internal conflict raging within the newsroom. For Brett Grubisic, the decision to have a queer issue with such a shocking cover was a difficult one to make.

“There’s that long kind of debate in gay politics . . . about whether the successful way [in advocacy] is through making yourself appealing, or . . . shoving your politics down somebody’s throat,” says Grubisic. “If there was any kind of conflict, it was about how do we pitch our politics to a population? Do we make them like us, or do we just make them hear our voices?”

It’s a fine line to walk, and some felt the newspaper had crossed over too far into shocking for the sake of shock value. Susan MacDonald was a Masters student in the English department at the time, and she wrote in to say how unimpressed she was with the cover.

“Your cover hardly created a sensitive context in which to approach [gender] issues; it simply created the opportunity for students to once again approach the subject of genitalia in ever-so-imaginative language,” MacDonald wrote. “Homosexuality involves much more than genital relationships. So much for destroying hurtful stereotypes about dykes and queers.”

Some responses to the issue in total were less reasonable.

“I am getting tired of homosexuals whining about oppression, when I don’t see any evidence of it,” one letter wrote. “On this campus, the voices of homosexuals are ALL that is heard.”

“I would like to address the word homophobic,” said another letter-writer. “Stop calling me that. I am not scared of queers, or of the thought of queer sex. Simply, it nauseates me.”

More responses to the cover which ran in the following week’s issue are included below:

- This article ran in the Times Colonist shortly after the cover’s publication. Via Times Colonist archives

Alisa Gordaneer also worried that too many people were missing the point of a queer issue. Even though word of the cover was spreading quickly—local news outlets like the Times Colonist had begun to pick up the story—people were more interested in the reaction it created than the content itself. Gordaneer says the cover had “fundamentally” detracted from the message.

“People were freaked out just by the cover and they didn’t even open the inside,” she says. “It might have been kind of difficult for people to pick up the paper and hold it up and be seen reading it.”

But despite Gordaneer’s concerns, and the public’s reaction, none of the former Martleteers that I talked to believed they had done the wrong thing by publishing the cover. The idea behind the issue had been to allow a platform for queer voices at UVic. People were free to disagree with the message, but Gordaneer, MacKinnon, and the rest of the staff felt a duty in promoting the voices of a community that was struggling to be heard.

“I don’t think it was about shocking students. I think there was a point,” Andrew MacLeod says. “The artist who put [the cover] together had something serious that he was trying to say. Something that was important to him, that was very true to him. Was it something that was true to everyone? Probably not.”

Bryan Young worried that people would take the cover the wrong way, and argued with Christopher Lefler about the the appropriate way to represent themselves and the larger queer community through the newspaper.

It was in these conversations that Lefler would convince Young why the cover was needed.

“I think my main thing was about perceptions,” Young says. “[I remember thinking], ‘I don’t know how this is going to fly,’ ‘We’re going to get into trouble,’ ‘I don’t want people to think . . . the worst of us,’ at a time where we’re just starting to try to come out . . .

“But [Lefler] was very persuasive in saying, if we’re truly interested in ‘coming out’, we need people to understand what this is about . . . ‘This is about our bodies. This is about how our bodies behave. This isn’t about how we dress, it’s about who we love. And we need to talk about that.’ And I agreed.”

Unfortunately, I was never able to speak directly to Lefler for this article. He had found his way into the headlines a few years later when, in 1995, an art project of his featured a letter from a cabinet official in the Saskatchewan provincial government that purportedly said that official was secretly lesbian. The project, designed as part of a Master’s degree at the University of Saskatchewan, was deemed to be defamatory and was cancelled. Lefler lost $9 500 in grant money and was expelled.

According to his friends, Lefler changed his name sometime between 1995 and now. I asked them to pass my information along to him, which they assured me they did. I never heard from him.

My first interview for this feature was with Andrew MacLeod. We met at a corporate coffee shop in Oak Bay and spoke for 40 minutes. He was gracious with his time and answers and gave me more than enough material to work with.

At the end of our conversation, MacLeod stood up to shrug on a coat and hat. As I turned off my recorder, he asked me if I wanted to know whose genitals were on the cover.

“I didn’t think to ask,” I responded, honestly. “Whose were they?”

MacLeod smiled as he turned to leave the coffee shop. “That’s not for me to tell you.”

No one ever did. Throughout my research, each ex-Martleteer asked me if I wanted to know who had been photographed back in 1992 but not one person revealed any names. I kind of liked not knowing. It kept a sense of mystery around the piece.

Like the question of “whose genitals are these?” there is a lot I will likely never know about the cover. What was it like to be openly queer at UVic in the 1990s? How did Lefler feel about the reaction his art had received? Did the Martlet do the right thing in publishing it?

It may seem pointless to ask so many questions about a couple of photos, but MacLeod himself put it best in that coffee shop:

“Does the cover of a student newspaper have the power to change the world? No. But then, what does?”

All I do know is that if a cover can still generate conversation 25 years past its publication date, it fulfilled the goals of those who helped conceive of it. That was why MacKinnon and his fellow Martlet contributors were so excited to find out their papers were being thrown away. People got the message—disagreed with it, sure, but heard it nonetheless.

[Editor’s note: In presenting this cover, the Martlet acknowledges that it does not reflect contemporary discourse surrounding gender identity and sexual identity, and how it could possibly be viewed as problematic today. For example, the term “womyn” has been used to specifically denote women who were identified as female at birth, and its use in some feminist circles has been trans- exclusionary and transphobic. Additionally, this cover presents a gender binary that is cis-normative and does not account for a transgender experience. For a more in depth discussion of these issues, read our latest editorial.]

Correction: We’ve corrected an instance in this article where we refer to one set of genitalia on the cover as a vagina, when the term ‘vulva’ would be more accurate. We’ve also edited the content warning to remove the labelling of “male and female” genitalia, recognizing that doing so implicitly gendered them. We regret the errors.